BABA YAGA

Baba Yaga by Fabiano Mello de Lima. A digital sculpture by the storyboard artist Fabiano Mello de Lima that desexes Baba Yaga. An original feature is the pair of small hands protruding from the aperture in the vehicular mortar on which she is seated, presumably belonging to a captured child who will become Baba Yagas meal and end up as a skull to be added either to Baga Yagas fence or to those dangling from the mortar. Illustration by Fabiano Mello de Lima, Fabiano Lima .

BABA YAGA

The Wild Witch of the East in Russian Fairy Tales

Introduction and Translations by Sibelan Forrester

Captions to Images by Helena Goscilo

Selection of Images by Martin Skoro and Helena Goscilo

Edited by Sibelan Forrester, Helena Goscilo, and Martin Skoro

Foreword by Jack Zipes

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

With Support and Assistance from The Museum of Russian Art, 5500 Stevens

Ave. S., Minneapolis, MN 55419, http://tmora.org

A good faith effort was made to identify all artists or copyright holders of the illustrations used.

Copyright 2013 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2013

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

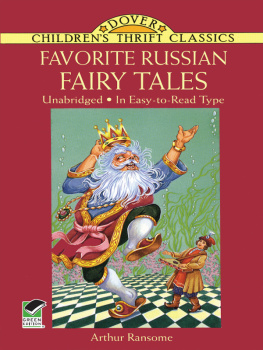

Baba Yaga : the wild witch of the East in Russian fairy tales / introduction and translations by Sibelan Forrester ; captions to images by Helena Goscilo ; selection of images by Martin Skoro and Helena Goscilo ; edited by Sibelan Forrester, Helena Goscilo, and Martin Skoro ; foreword by Jack Zipes.

pages : illustrations ; cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-61703-596-8 (cloth : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-1-61703-778-8 (ebook) 1. Baba Yaga (Legendary character) 2. TalesRussia. I. Forrester, Sibelan E. S. (Sibelan Elizabeth S.), translator, editor of compilation. II. Goscilo, Helena, 1945, editor of compilation. III. Skoro, Martin, editor of compilation. IV. Zipes, Jack, 1937, writer of added commentary.

GR75.B22B22 2013

398.20947dc23 2013003373

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

CONTENTS

Illustration by Ivan Bilibin (18761942).

FOREWORD

Unfathomable Baba Yagas

JACK ZIPES

Illustration by Viktor Vasnetsov (18481926).

In Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale, the most thorough study of Baba Yaga to date, Andreas Johns demonstrates that Baba Yaga has appeared in hundreds if not thousands of folktales in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus since the eighteenth century, if not earlier. She is not just a dangerous witch but also a maternal benefactress, probably related to a pagan goddess. Many other Russian scholars such as Joanna Hubbs in Mother Russia: The Feminine Myth in Russian Culture, Linda Ivanits in Russian Folk Belief, and Cherry Gilchrist in Russian Magic: Living Folk Traditions of an Enchanted Landscape have confirmed this: Baba Yaga transcends definition because she is an amalgamation of deities mixed with a dose of sorcery. Though it is difficult to trace the historical evolution of this mysterious figure with exactitude, it is apparent that Baba Yaga was created by many voices and hands from the pre-Christian era in Russia up through the eighteenth century when she finally became fleshed out, so to speak, in the abundant Russian and other Slavic tales collected in the nineteenth century. These Russian and Slavic folktales were the ones that formed an indelible and unfathomable image of what a Baba Yaga is. I say a Baba Yaga, because in many tales there are three Baba Yagas, often sisters, and in some tales a Baba Yaga is killed only to rise again. And no Baba Yaga is exactly like another.

In Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale, the most thorough study of Baba Yaga to date, Andreas Johns demonstrates that Baba Yaga has appeared in hundreds if not thousands of folktales in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus since the eighteenth century, if not earlier. She is not just a dangerous witch but also a maternal benefactress, probably related to a pagan goddess. Many other Russian scholars such as Joanna Hubbs in Mother Russia: The Feminine Myth in Russian Culture, Linda Ivanits in Russian Folk Belief, and Cherry Gilchrist in Russian Magic: Living Folk Traditions of an Enchanted Landscape have confirmed this: Baba Yaga transcends definition because she is an amalgamation of deities mixed with a dose of sorcery. Though it is difficult to trace the historical evolution of this mysterious figure with exactitude, it is apparent that Baba Yaga was created by many voices and hands from the pre-Christian era in Russia up through the eighteenth century when she finally became fleshed out, so to speak, in the abundant Russian and other Slavic tales collected in the nineteenth century. These Russian and Slavic folktales were the ones that formed an indelible and unfathomable image of what a Baba Yaga is. I say a Baba Yaga, because in many tales there are three Baba Yagas, often sisters, and in some tales a Baba Yaga is killed only to rise again. And no Baba Yaga is exactly like another.

A Baba Yaga is inscrutable and so powerful that she does not owe allegiance to the Devil or God or even to her storytellers. In fact, she opposes all Judeo-Christian and Muslim deities and beliefs. She is her own woman, a parthogenetic mother, and she decides on a case-by-case basis whether she will help or kill the people who come to her hut that rotates on chicken legs. She shows very few characteristics and tendencies of western witches, who were demonized by the Christian church, and who often tend to be beautiful and seductive, cruel and vicious. Baba Yaga sprawls herself out in her hut and has ghastly featuresdrooping breasts, a hideous long nose, and sharp iron teeth. In particular, she thrives on Russian blood and is cannibalistic. Her major prey consists of children and young women, but she will occasionally threaten to devour a man. She kidnaps in the form of a Whirlwind or other guises. She murders at will. Though we never learn how she does this, she has conceived daughters, who generally do her bidding. She lives in the forest, which is her domain. Animals venerate her, and she protects the forest as a mother-earth figure. The only times she leaves it, she travels in a mortar wielding a pestle as a club or rudder and a broom to sweep away the tracks behind her. At times, she can also be generous with her advice, but her counsel and help do not come cheaply, for a Baba Yaga is always testing the people who come to her hut by chance or by choice. A Baba Yaga may at times be killed, but there are others who take her place. Baba Yaga holds the secret to the water of life and may even be Mother Earth herself. This is why Baba Yaga is very much alive today, and not only in Mother Russia, but also throughout the world.

While a Baba Yaga is still a uniquely Russian folk character, she has now become an international legendary figure and will probably never die. Stories about her dreadful and glorious deeds circulate throughout the world in translation. Fabulous book illustrations, paintings, and colorful designs imprinted, painted, or carved on all kinds of artifacts have flourished in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. She is often the star figure in childrens picture books, even though she functions primarily as a witch. Films, animated cartoons, and digital images have portrayed a Baba Yaga as omnipotent, dreadful, and comical. In many of the images, she is shown flying about in her mortar and wielding her pestle as in the illustrations by Viktor Bibikov, Dimitri Mitrokhin, and Viktor Vasnetsov. She seems always obsessed and vicious. Some artists such as Aleksandr Nanitchkov and Rima Staines are fond of showing her in weird types of huts on chicken legs. No matter how she is portrayed, there are always hints of her Russian heritage in the images. The emphasis on traditional dress and nineteenthcentury styles are especially evident in the famous illustrations for Vasilisa the Beautiful by Ivan Bilibin and the gouache paintings by Boris Zvorykin for

Next page

In Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale, the most thorough study of Baba Yaga to date, Andreas Johns demonstrates that Baba Yaga has appeared in hundreds if not thousands of folktales in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus since the eighteenth century, if not earlier. She is not just a dangerous witch but also a maternal benefactress, probably related to a pagan goddess. Many other Russian scholars such as Joanna Hubbs in Mother Russia: The Feminine Myth in Russian Culture, Linda Ivanits in Russian Folk Belief, and Cherry Gilchrist in Russian Magic: Living Folk Traditions of an Enchanted Landscape have confirmed this: Baba Yaga transcends definition because she is an amalgamation of deities mixed with a dose of sorcery. Though it is difficult to trace the historical evolution of this mysterious figure with exactitude, it is apparent that Baba Yaga was created by many voices and hands from the pre-Christian era in Russia up through the eighteenth century when she finally became fleshed out, so to speak, in the abundant Russian and other Slavic tales collected in the nineteenth century. These Russian and Slavic folktales were the ones that formed an indelible and unfathomable image of what a Baba Yaga is. I say a Baba Yaga, because in many tales there are three Baba Yagas, often sisters, and in some tales a Baba Yaga is killed only to rise again. And no Baba Yaga is exactly like another.

In Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale, the most thorough study of Baba Yaga to date, Andreas Johns demonstrates that Baba Yaga has appeared in hundreds if not thousands of folktales in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus since the eighteenth century, if not earlier. She is not just a dangerous witch but also a maternal benefactress, probably related to a pagan goddess. Many other Russian scholars such as Joanna Hubbs in Mother Russia: The Feminine Myth in Russian Culture, Linda Ivanits in Russian Folk Belief, and Cherry Gilchrist in Russian Magic: Living Folk Traditions of an Enchanted Landscape have confirmed this: Baba Yaga transcends definition because she is an amalgamation of deities mixed with a dose of sorcery. Though it is difficult to trace the historical evolution of this mysterious figure with exactitude, it is apparent that Baba Yaga was created by many voices and hands from the pre-Christian era in Russia up through the eighteenth century when she finally became fleshed out, so to speak, in the abundant Russian and other Slavic tales collected in the nineteenth century. These Russian and Slavic folktales were the ones that formed an indelible and unfathomable image of what a Baba Yaga is. I say a Baba Yaga, because in many tales there are three Baba Yagas, often sisters, and in some tales a Baba Yaga is killed only to rise again. And no Baba Yaga is exactly like another.