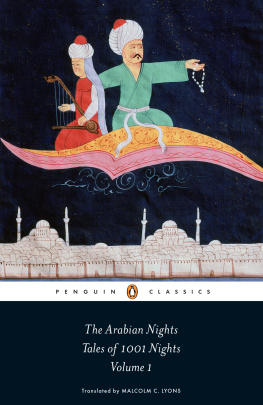

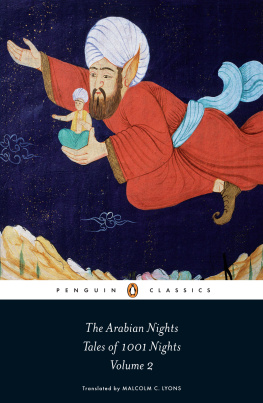

Tales from 1,001 Nights

Aladdin, Ali Baba and Other Favourite Tales

Translated by MALCOLM C. LYONS ,

with URSULA LYONS

Introduced and Annotated by ROBERT IRWIN

PENGUIN CLASSICS

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN CLASSICS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published in three volumes by Penguin Classics 2008

This abridged edition published 2010

All stories translation copyright Malcolm C. Lyons, 2008 except the translation of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves Killed by a Slave Girl and The Story of Aladdin copyright Ursula Lyons, 2008

Introduction, Glossary and Further Reading copyright Robert Irwin, 2010

The moral right of the translators and introducer has been asserted

Cover images The Art Archive

Cover design Coralie Bickford-Smith

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic,mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-141-96587-1

Editorial Note

This selection of stories from The Arabian Nights (also known as The Thousand and One Nights) is taken from the three-volume Penguin Classics edition (2008), the first complete translation of the Arabic text known as the Macnaghten edition or Calcutta II since Richard Burtons famous translation of it in 18858.

In addition to Malcolm Lyonss translations from the Arabic text of Calcutta II, this selection includes Ursula Lyonss translations of the tales of Aladdin and Ali Baba from Antoine Gallands eighteenth-century French. (For these stories no original Arabic text has survived and consequently they are classed as orphan stories.)

For this selected edition, the nights format has been removed, but the nights covered by each story cycle are indicated in a note at the end of each chapter. As the two orphan stories are not included within the nights structure (and neither are the opening and concluding chapters, which frame the stories told by Shahrazad), no notes are given for these.

As often happens in popular narrative, inconsistencies and contradictions abound in the text of the Nights. It would be easy to emend these, and where names have been misplaced this has been done, to avoid confusion. Elsewhere, however, emendations for which there is no textual authority would run counter to the fluid and uncritical spirit of the Arabic narrative. In such circumstances no changes have been made.

Introduction

In the caliphs palace, a girl is frying multi-coloured fish when a woman with a wand bursts through the wall and demands to know of the fish if they are true to their covenant A young man mounts a flying horse; the horse strikes out one of his eyes with a lash of its tail and lands him on a building where he will encounter ten more one-eyed men A travelling merchant is entombed alive with his deceased wife It was the strangeness of the plotting and imagery, as well as the freedom from classical constraints derived from such authors as Homer, Ovid and Virgil, that appealed to the earliest Western readers of The Thousand and One Nights (best known in English as The Arabian Nights). Read Sinbad and you will be sick of Aeneas, as the eighteenth-century gothic novelist Horace Walpole declared. Yet behind the apparent wildness of the stories, there are patterns and correspondences and the playing off of themes and images against one another by the tales anonymous authors.

One Thousand and One Nights is a marvel of Eastern literature, according to the Nobel Prize-winning Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk in his essay Love, Death and Storytelling (New Statesman, 26 December 2006). It was a book that was familiar to Pamuk since childhood, but he has recently described how he decided to reread it in order to understand what fascinated Western authors like Stendhal, Coleridge, De Quincey and Poe in these stories and made the book a classic: I saw it now as a great sea of stories a sea with no end and what astounded me was its ambition, its secret internal geometry I was able finally to appreciate One Thousand and One Nights as a work of art, to enjoy its timeless games of logic, of disguises, of hide-and-seek, and its many tales of imposture.

It seems most probable that the core of the Arabic story collection, Alf Layla wa-Layla (The Thousand and One Nights), originated in a fairly brief and simple form in ancient India. Then, some time before the ninth century AD , these Sanskrit tales were translated into Persian under the title Hazar Afsaneh (The Thousand Tales) and doubtless some Persian stories were added to this collection. By the ninth century at the latest, an Arabic version known as Kitab Hadith Alf Layla (The Book of the Tale of One Thousand Nights) was in circulation. But The Thousand and One Nights in the form we have it today, with its elaborate frame story about King Shahriyar and the storyteller Shahrazad, was compiled much later. The oldest substantially surviving manuscript of the Nights seems to date from the late fifteenth century. In the opening frame story, which is included in this edition, Shahrazad tells Shahriyar stories night after night in order to postpone her execution. The nights function as story breaks; there are not actually a thousand and one stories. Some stories are very short, others very long, told over many nights. Some are about criminals, some about saints. Some feature magic and monsters, while others centre on commercial transactions or romantic assignations. It is the sheer variety of stories that gives the Nights its unique quality.

In bookshops and libraries it is common to find the Nights shelved with fairytales, even though fairies feature very rarely in the Arab stories. But a fairytale is not defined by the presence of fairies within it. Such Western stories as Puss in Boots or Bluebeard have no fairies in them, but they are still universally regarded as fairytales. A fairytale, rather, is a story that relies on the fantastic to induce wonder. In this sense, a very high proportion of the stories in the Nights can be regarded as fairytales. Even so, there are also plenty of stories in which the fantastic and the supernatural do not feature stories about cunning adulterers, learned slave girls, pious hermits, master criminals, benevolent or despotic rulers and so on. Jorge Luis Borges once remarked that all great literature becomes childrens literature. (Doubtless he was thinking of such works as