Contents

Guide

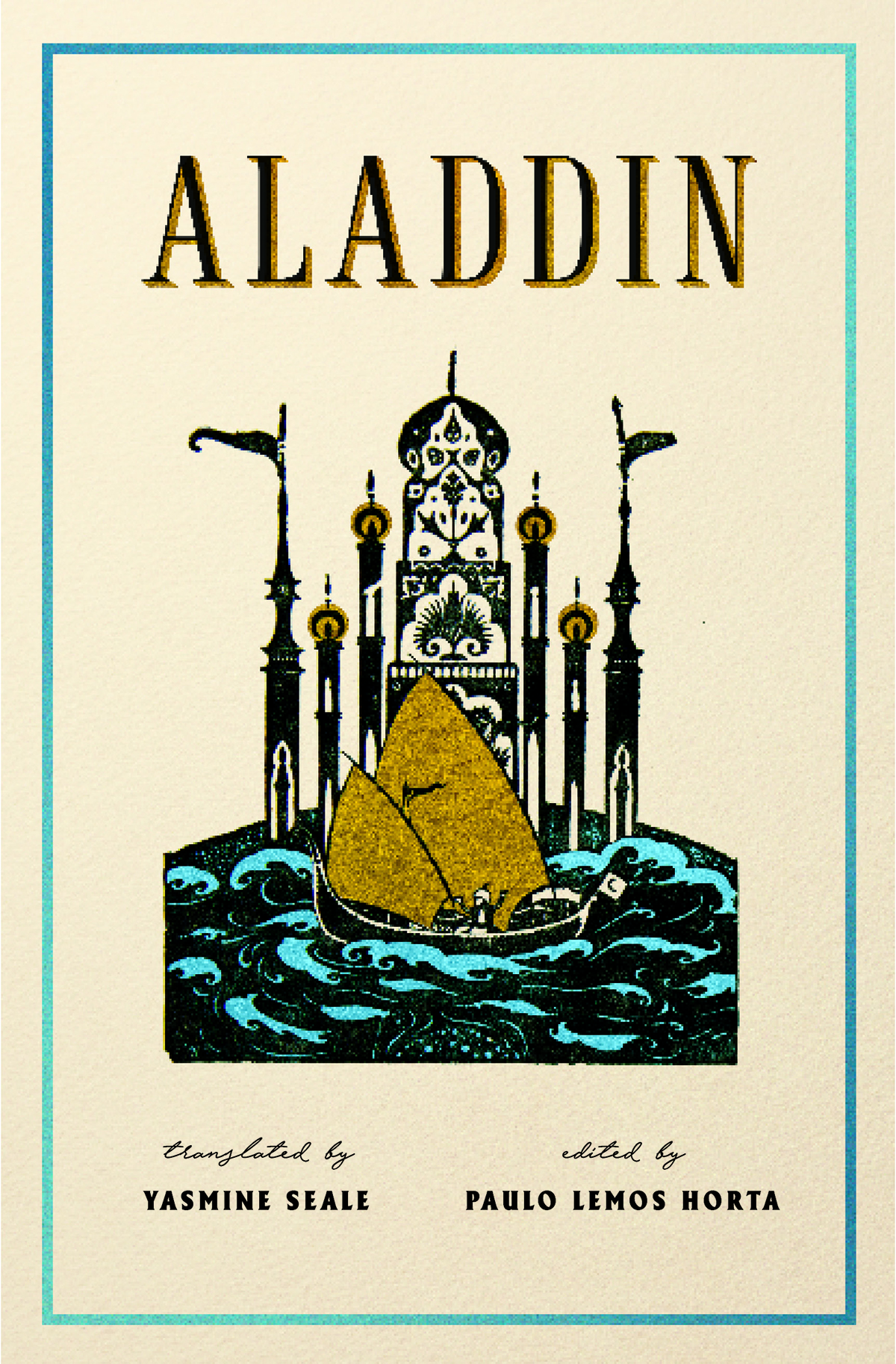

ALADDIN

A New Translation

TRANSLATED BY YASMINE SEALE

EDITED BY PAULO LEMOS HORTA

Copyright 2019 by Liveright Publishing Corporation

Translation copyright 2019 by Yasmine Seale

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Jacket design by Zoe Norvell

Jacket illustration by Edward Dulac, from Sinbad the Sailor and Other Stories from the Arabian Nights published by Hodder & Stoughton, 1914

Book design by Chris Welch

Production manager: Beth Steidle

ISBN 978-1-63149-516-8

ISBN 978-1-63149-517-5 (ebk.)

Liveright Publishing Corporation, 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

CONTENTS

O ne of the worlds most famous and beloved fairy tales, Aladdin, or the Wonderful Lamp, has been retold and adapted time and time again since it first appeared in French in the early eighteenth century. It may seem surprising that a story so powerfully associated with the collection of Arabic tales known as the Thousand and One Nights should have come down to us through Frenchbut it is also apt. The tale has never stopped traveling. Authors from Charles Dickens and Dante Gabriel Rossetti to Clarice Lispector and Salman Rushdie have written about their experiences of encountering the story as children. My own mother often regaled me with the story of her first encounter with the tale, as a six-year-old orphan receiving her first gift of the Arabian Nights from her adoptive father in the north of Brazil. Through the centuries, the tales broad and lasting appeal rests on its ability to encompass both our wildest longings and our deepest uncertaintiesboth the childhood dream of wish fulfillment and the terrors of coming of age.

At the heart of the story is the mystery surrounding Aladdin himself. Why should he, a boy of little talent or ambition, have been chosen for the extraordinary adventures that await him? Why should he, rather than another, have the lamp?

In an attempt to answer this riddle, scholars and screenwriters alike have invented variations on the tale that have the boy perform some meritorious act to demonstrate that he deserves the lamp. Folklorists have identified precedents in Buddhist tales where characters save animals from danger and are rewarded with a wishing stone. The Disney film portrays Aladdin as a diamond in the rough, forced by poverty to steal but generously giving to those who are less fortunate than himself. Others have argued that it is in fact the lamp that makes the man. Richard Francis Burton, the infamous adventurer and translator of the Arabian Nights , suggested that the lamp had the power to alter the physique and morale of the owner and therefore to transform the raw youth into a finished courtier, warrior, statesman. The scholar Tzvetan Todorov sees Aladdin as part of a line of what he calls narrative men, devoid of character other than the marvels and machinations of fate that work through them.

Like many a comic book herothink of Peter Parker receiving a bite from a radioactive spiderAladdin is transformed into the tales hero by coming into possession of the lamp. Once in command of it, and its slave the jinni, Aladdin is no longer a passive recipient of magical good fortune but an agent of his own fate. The heroine of the story, the princess Badr al-Budur, is equally active in shaping its outcome, saving Aladdins life by outwitting the magician in the tales climax.

Aladdin has a peculiar relationship to the Thousand and One Nights . First added to the collection in the French translation produced by Antoine Galland in early eighteenth century Paris, the tale of Aladdin has not been found in any authentic Arabic manuscript predating this telling. Galland added the story, along with other tales such as Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, to his French collection, after running out of stories to translate from his Arabic manuscript of the Thousand and One Nights . In his diary, Galland claimed that a Maronite Christian traveler from Aleppo named Hanna Diyab told him these stories during a visit to Paris in 1709, and, in the case of Aladdin, gave him a manuscript of the tale. While some scholars have doubted the existence of this mysterious Syrian storyteller, the recent discovery of Diyabs memoir chronicling his travels to Paris confirms that he both met the French translator and provided him with stories with which to complete his translation of the Thousand and One Nights .

Despite this revelation, fundamental questions regarding the origins of Aladdin remain unanswered. Whose story is Aladdin really? There is broad agreement that, compared to the original Arabic tales of the Thousand and One Nights , Aladdin and the other tales told to Galland by Diyab draw more heavily on the marvelous, in the sense of both material treasures and supernatural creatures and events. Some have attributed these differences to the imagination of the French Orientalist Galland, who used the raw material of a text of unknown provenance to channel his own conception of an exotic East. The novelist Marina Warner has pointed to the presence of popular eighteenth century storytelling elementstalismans, spoken charms, and the inversion of social orderas evidence of a French hand in Aladdins composition. The discovery of Diyabs memoir, however, suggests that the gift of the tale to Galland was the product of the fertile imagination of a young Syrian Maronite raised within the storytelling culture of a caravan city. The novelist and Arabist Robert Irwin has argued that many of the elements identified as peculiar to a European narrative tradition in Aladdin have clear precedents in popular Arabic literature. The Thousand and One Nights contains other stories of lazy youths undeserving of their good fortune, and other characters who conjure jinn from rings and build palaces to woo the objects of their desire.

I find it intriguing to read the tale of Aladdin alongside Diyabs record of his own youthful adventures as he journeyed from Aleppo to Paris and the royal court at Versailles in defiance of his familys wishes. The similarities between the two narratives might help explain his attraction to the tale that he provided to Galland, even if he did not have a hand in its composition. The youngest of several brothers who apprenticed with a French merchant in Aleppo, Hanna Diyab understood the appeal of the magicians empty promise to help Aladdin establish himself as a cloth merchant in the market. This magician, who lures Aladdin into his service by pretending to be his uncle, carries echoes of the French adventurer Paul Lucas, who enticed Diyab to accompany him on a treasure-hunting journey through the Mediterranean with the promise of a position at the French court. Lucass reputation rested on the various false identities he assumed and on his purported skill in the use of amulets and charms to heal ailments. In his memoir, Diyab relates the Frenchmans claim that he could harness the power of the philosophers stone against the ravages of age. Strangely enough, the first tomb-raiding expedition that Diyab describes in his account of his time with Lucas yielded both a ring and a lamp.