A Page Right Out of History

American fans of Japanese animation wouldnt have Pokmon, Akira, or Totoro to enjoy if it werent for Walt Disney, cable television, and the VCR. An informal history of anime in the United States, going back to 1963.

A lot of Japanese animenot all of it by any means, but certainly more than animation in the Westis aimed at viewers with double-digit ages and triple-digit IQs. As they did with automobiles, the Japanese have taken an American creation and reworked it into something far beyond what its creators considered to be the state of the art. Toontown, like Detroit, has to play some serious catch-up if it wants to stay in the game.

Hooray for Hollywood

Ironically, there would be no animation in Japan or anywhere else had it not been pioneered and developed in the United States shortly after movies themselves were invented. Of the two mainstay studios in American animation between the World Wars, one didnt last very long. Brothers Max and Dave Fleischer had some very popular characters to their credit. These included the animated versions of the Superman comic book and of the newspaper comic Popeye, and especially the cartoon vamp Betty Boop. Max Fleischer also invented the rotoscoping technique of filming live actors, then drawing cartoons based on their movements. This accounted for the realistic look of the title character in the 1939 Fleischer feature Gullivers Travels, while the little people of Lilliput and Blefuscu were blatantly cartoony.

The top of the animation mountain, of course, was Walt Disney. He pioneered sound and color, as well as avant-garde techniques that would hardly ever be used again. If people anywhere in the world saw animation at all before 1941, it was probably Disney animation. Disney broke new ground with the 1937 feature-length Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. For the next four decades Hollywood animated features followed the lead of Walt Disney in treating animation as a family medium: targeted at children, but with the occasional bit of in-joking dialogue or eye candy for the grownups who brought the children into the theater in the first place. (And singing; dont forget singing. That deserves its own chapter, especially in light of Japans take on pop music and anime. For now, suffice it to say that, because Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was structured along the lines of European operetta, with songs aplenty, some animated features in the West still feel obligedsixty years laterto break into song every five minutes, even if theres no particular reason.)

However, cartoons in the West were often just a sideshow. Animation before television, after all, usually meant theatrical short subjects, and the only place to see animation was at the movies.

The Doctor Is In

At first the Japanese took their cues on animation from the same medium American television animation did: Disneys animated theatrical short subjects and feature films. But Disneys early animationboth the artistic technique and the humanist philosophybecame the subjects of study as well as entertainment for a medical student named

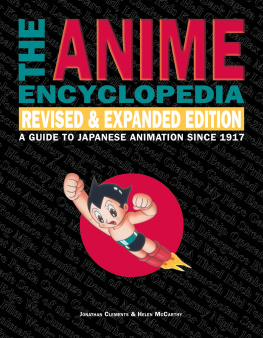

The transition to television animation was thus a short and simple one. It was helped along when Dr. Tezuka created Japans first animated TV superstar. While Mickey Mouse, Tom and Jerry, and Bugs Bunny were created for the movies and then found life on American television, a robot that looked like a young boy moved from the comic-book pages directly to the small screen, and promptly became one of the most memorable characters of all time, on both sides of the Pacific. Published in Japan for years as Tetsuwan Atomu (The Mighty Atom) and animated by Tezukas own Mushi Productions studio, hes still remembered outside Japan as Astro Boy. With spiky hair, eyes as big as fists, rockets in his feet, and machine-guns in his butt, Atomu was a new kind of robot for a post-Occupation Japan. His enemies arent just bug-eyed monsters from outer spacehe has the ability to tell if people are good or evil just by looking at them, so he spends time with law enforcement as well as his family. (He was originally created by a mad scientist to replace the scientists son, killed in a traffic accident, but by the end of the series Atomu acquired two robot parents and two younger siblings.)

Watching Astro Boy here and now, and especially Astro Boys initial episode, first broadcast in 1963, is something that will stay with you even in the wake of high-tech marvels such as Akira and Ghost in the Shell .

At times the black-and-white pictures are as primitive as an old Popeye short; at times the graphic quality rises to the level of Dumbo. But there is also the overall difference from typical Western storytelling, whose joys cannot be overstated. Watch Atomu rise up from the laboratory table. This isnt a parody of Frankenstein movies; this is the creation of a lifetentative, inquisitive, singular. Something in the way he moves and gestures tells us that, at some level, this really is a wide-eyed child taking his first steps. Look at the castoff performers at the Robot Circus, consigned to the junk heap only because cute is boring. Consider the ringmaster as a low-rent Stromboli from Pinocchio; then watch as the Robot Circus burns down, and as Atomu rescues the ringmaster. From his hospital bed, the ringmaster finds out who saves hima scene that would lead immediately to repentance in the Westbut then the sonovabitch still claims he owns Atomu, in spite of robots having been granted civil rights. (Unlike Disney features, which didnt try to be topical except for a few pop culture references, Tetsuwan Atomu consciously and deliberately mirrored the American civil rights struggles of the day. Its hard to think of an American television serieslive or animatedthat did the same, and its equally hard to think of a twentieth-century Disney movie that could be called topical.)

Theyre Coming to America

Not long after its premiere on Japanese TV on the first day of 1963, Atomu made the jump to American television. Back in the early 1960s, most TV stations in the United States were not even on the air twenty-four hours a day, and the notion of cable TV with hundreds of channels was the stuff of science fiction. This was a time of growth and expansion, however, with color broadcasting just around the corner. The growing need for programming coincided with the experimental approach in those days of broadcasters who were willing to try just about anything. Anime were especially welcome because of their lack of ethnic specificity. One of the conventions of anime (to be discussed later) was to draw characters as if they were American, or at least white. Even if the characters were supposed to be Japanese, they seldom looked Japanese. Thus, translation was no trouble at all; characters could be renamed, relationships and motivations juggled, and plots rewritten with relative ease. This became a major consideration later, when Japanese plots and pictures went far beyond what was permitted by American broadcast standards., based on a manga by Mitsuteru Yokoyama, hit the West in 1965 as Gigantor. He was not, however, the star of the showthis robot, unlike Atomu, was not a sentient being but a huge (forty-foot-tall) machine controlled by a small boy, the son of the inventor. This created an archetype for several a boy and his robot series to follow, from Johnny Socko to Evangelion.

Dr. Tezuka followed up Astro Boy

Next page