How Dead Languages Work

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Coulter H. George 2020

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2020

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019950243

ISBN 9780198852827

ebook ISBN 9780192594143

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Acknowledgments

Languages, especially dead ones, are an endless source of intellectual delight, and my first debt of gratitude is to the many outstanding teachers Ive had the immense good fortune to study with over the years. Collectively, they have advocated for Greek, Latin, and all the rest of the languages I cover in this book in a kaleidoscopic variety of ways. While Harvey Yunis and James Clackson were particularly instrumental in giving me the intellectual tools to work with Greek and Latin, I would here especially like to record my gratitude to my Sanskrit teacher, the late Douglas Mitchell, who never ceased in his own inimitable manner to underline the importance of viewing every linguistic expression as possessed of its own unique value. I have learned much from all of them and, indeed, from the rich secondary literature in the fieldalthough I have preferred in what follows to give pride of place to the languages themselves rather than scholarly debates about controversial points, and so have been sparing with footnotes.

The opportunities provided by my home institution, the University of Virginia, were also crucial in seeing this project through. For several years I taught an introductory seminar for first-year undergraduates here, in which we looked at texts in seven different ancient and medieval languages over the course of the semester: I am grateful to my students for their willingness to serve as guinea pigs for much of the material in this book. The universitys generous Sesqui Leave (201617) freed up the time for actually writing much of the manuscript. And I especially continue to treasure the wonderful community of classicists here. For the many evenings of good cheer theyve provided, particular thanks go to the Wednesday Night Bachelorsincluding those who have moved away from Charlottesville and are much missed. Within their number, Tony Woodman deserves special credit for reading through the entire manuscript and saving me from one appallingly egregious Tacitean blunder, as does Elizabeth Meyer, whose unfailing thoughtfulness in her giving of gifts helped inspire me to write a book for non-specialists in the first place.

I am grateful to Oxford University Press for their work in seeing the book through production: Charlotte Loveridge, Georgie Leighton, Jenny King, Luca Prez, and Michael Janes have all been very helpful along the way. Both Joshua Katz and an anonymous reader for the press read through the whole book and offered invaluable corrections and suggestions. Hilary Bouxsein also improved the book immeasurably with her consistently perspicacious advice on multiple drafts as well as her general good spirits: I only hope that the words that follow are not only but downright . Finally, I would like to thank two other people, who, if indirectly and unknowingly, also played a role in the books genesis. My grandmothers, Miriam Young and Lila Gene George, to whom I owe my appreciation of good food, fine music, and countless else besides, always showed unflagging interest in my linguistic pursuits, no matter how arcane they became. While they are no longer with us, it is in no small part thanks to them that its been so important to me to explain to a wider audience what it is that I find so deeply fascinating about these languages.

Coulter H. George

Charlottesville

Contents

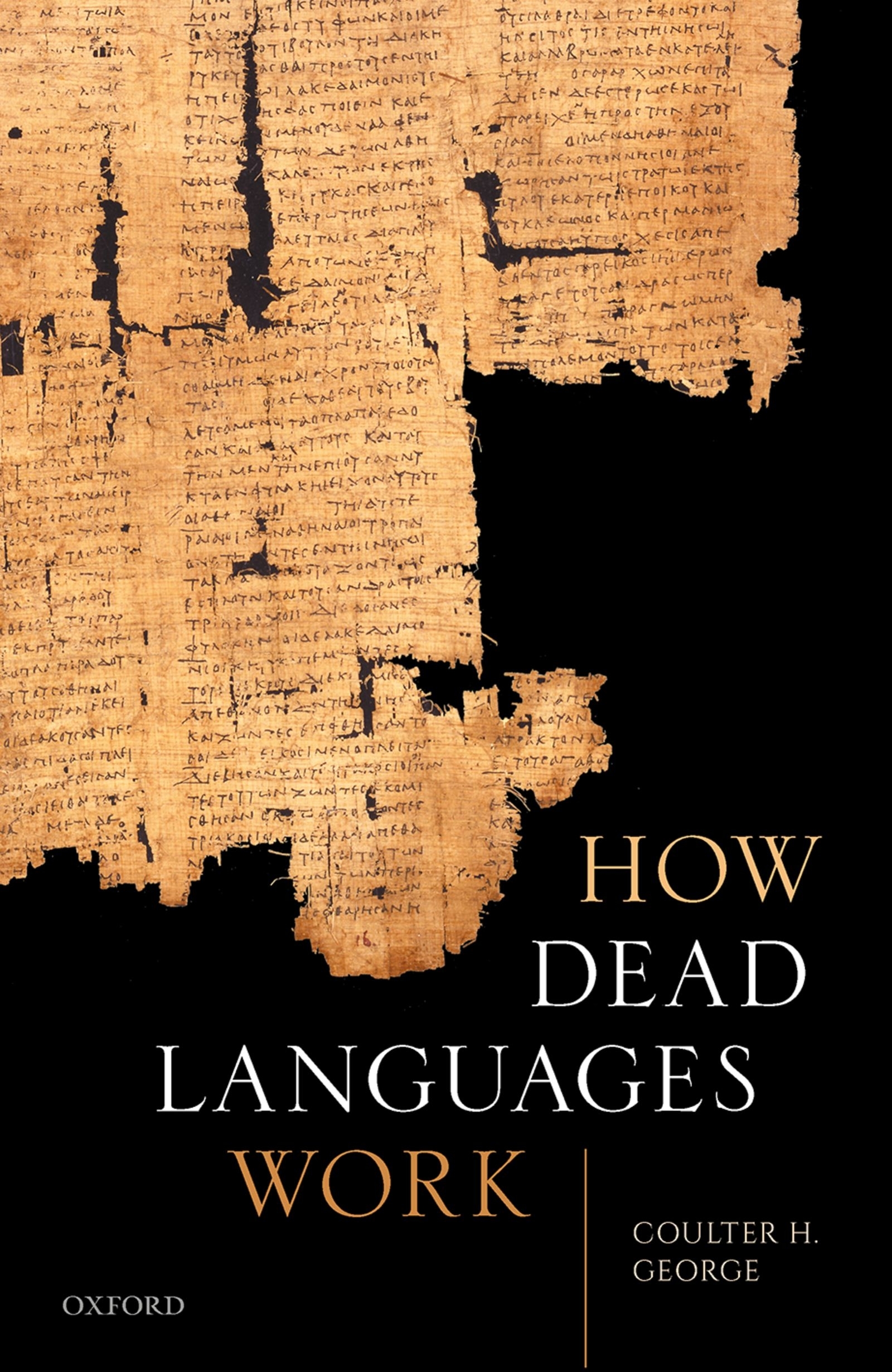

Why study Ancient Greek? Classicists are asked this all the time, and most will answer by pointing to the cultural achievements of the Greeks: this is the language of the first great epic poetry (Homer), historians (Herodotus and Thucydides), playwrights (Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes), and philosophers (Plato, Aristotle). Sure enough, wanting to gain a proper appreciation and understanding of any one of these texts would be more than enough reason on its own to learn Ancient Greek. But its not actually the main reason that Ive stayed fascinated by the language for so many years. When asked once what I liked best about Greek literature, I had to respond that it wasnt so much the content of all these great works, as impressive a cultural achievement as they represent, but rather everything about them that cant be translated into English. Because Greek, like all languages, has its own distinctive features that dont survive the process of translation. It has its own flavor. And this book is, in part, an attempt to explain to the Greekless reader what that means. Of course, the best way to understand what is lost in translation is to learn Greek. But its not as if most people have time for that, and it is with them in mind that Ive tried to explain as best as I can what makes Greek Greek.

But Greek is only the starting point for this book. Since its easier to understand what I mean by the flavor of a language if different languages are explicitly contrasted with one another, the book as a whole is designed as a tour of a half-dozen ancient languages of Europe and Asia, which offer among them enough variety to illustrate why the polyglot might think of languages as being like different cuisines, and why one would no more want to limit oneself to reading only Greek than to eating only at Italian restaurants. There is pleasure to be had not only in the connoisseurship of food and drink but also in that of language. In his recent book Babel No More: The Search for the Worlds Most Extraordinary Language Learners, Michael Erard does a good job of describing many of the characteristics of polyglots, but, by his own admission, he is not one himself, and because hes looking at his subject from the outside, he occasionally offers a view of the solitary language enthusiast as a somewhat joyless creature that is, to my mind, more dismal than is called for. I hope that this book will serve as a corrective to this portrayal by enabling readers to get a better sense of what polyglots see in all these different languages they devote so much time to. It may seem far-fetched to the layperson to view the mastering of pages of vocabulary lists and verb endings as funindeed, the sheer memorization necessary in order to read Greek or Latin is presumably the chief draw for very few people indeedbut this is to grossly discount the rewards that lie in wait once youve gone to that trouble and can finally read Homer or Virgil in the original language.