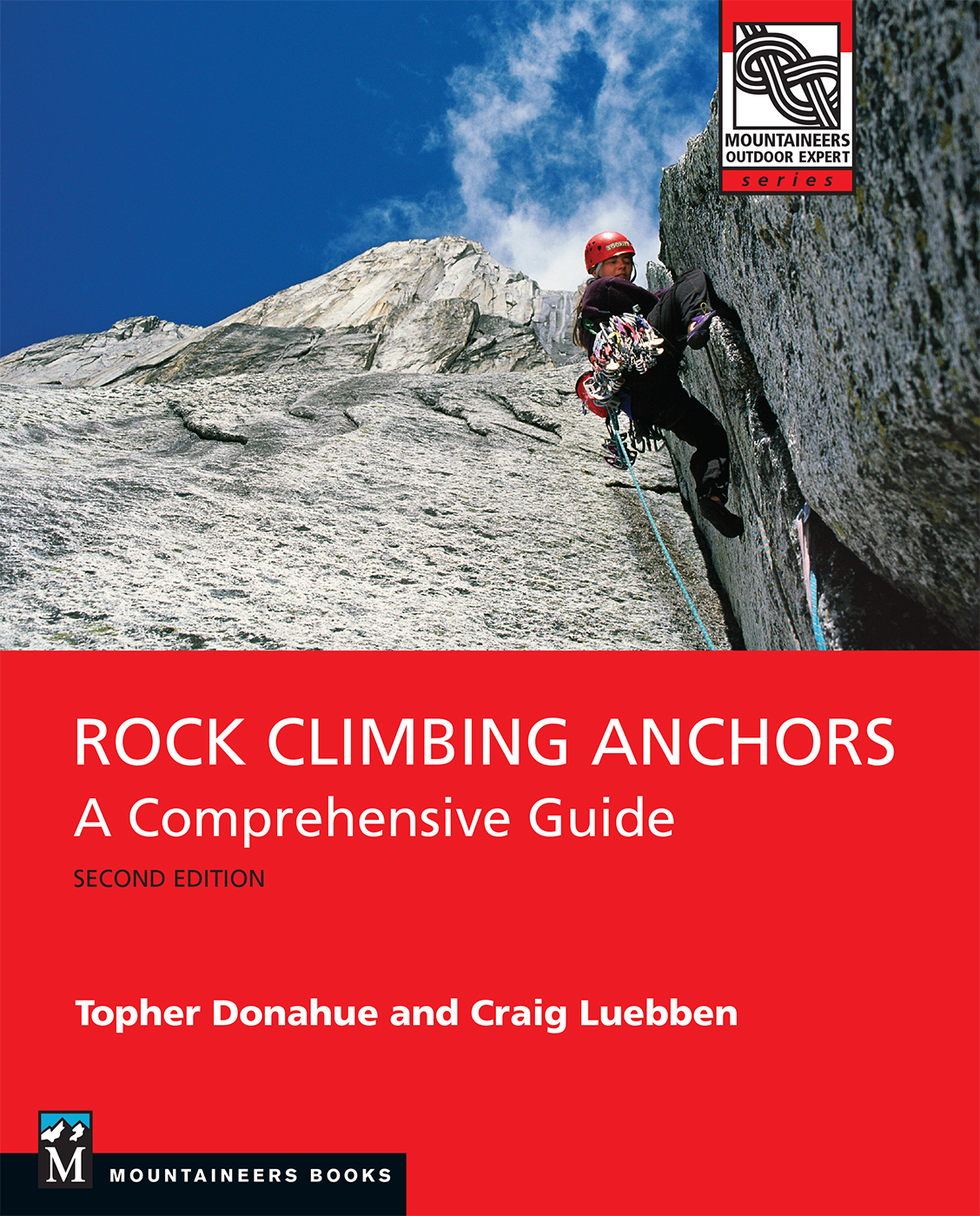

ROCK CLIMBING ANCHORS

A Comprehensive Guide

ROCK CLIMBING ANCHORS

A Comprehensive Guide

Topher Donahue and Craig Luebben

Second edition

This book is dedicated to everyone who believes that walls are for climbing.

MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS is dedicated to the exploration, preservation, and enjoyment of outdoor and wilderness areas.

1001 SW Klickitat Way, Suite 201, Seattle, WA 98134

800-553-4453, www.mountaineersbooks.org

Copyright 2019 by Topher Donahue and Silvia Luebben

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Printed in China

Distributed in the United Kingdom by Cordee, www.cordee.co.uk

First edition, 2007. Second edition, 2019.

Copyeditor: Erin Cusick

Design and layout: McKenzie Long

Cover photograph: Patience Gribble being careful not to take a factor-2 fall onto the belay anchor during the first ascent of Camerons Pillar (5.11+), South Howser Tower, Bugaboos, British Columbia Frontispiece: Alex Honnold treading the fine line between fun and danger in the Elbsandstein, Germany, on a pitch with only five pieces of gear in 50 meters

Photographers: Craig Luebben and Topher Donahue

Illustrator: Jeremy Collins

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file for this title at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018050955

Mountaineers Books titles may be purchased for corporate, educational, or other promotional sales, and our authors are available for a wide range of events. For information on special discounts or booking an author, contact our customer service at 800-553-4453 or .

Printed on FSC-certified materials

ISBN (paperback): 978-1-68051-140-6

ISBN (ebook): 978-1-68051-141-3

Contents

Vera Schulte-Pelkum entering the fun zone where the ground is far enough below that falls are safe and soft on Not My Cross to Bear (5.11), Penitente Canyon, Colorado

INTRODUCTION

Introduction

Climbing has always been a fascinating amalgamation of romantic adventure; a nerdy, science-experiment-like endeavor; and a physical, athletic pursuit. Craig Luebben, the author of the first edition of this book, was gifted in communicating all three of these seemingly disparate aspects of the sport. Thanks to climbing gyms and the social media culture, modern climbing tends to be seen as more athletic than scientific or adventurous, and as such, Craigs books may be more useful than ever before. When were getting pumped on a sport climb or checking out the instatweetchatbook feeds showing fit climbers after their latest send, its easy to forget the basic forces that make the sport both beautiful and dangerous. Craig, a scientist by training, introduced the first edition with a fundamental reminder of what makes climbing work:

Gravity: The tireless force that pulls two bodies together. The more massive the bodies and the closer they are, the stronger the pull. Earths huge mass creates an enormous gravitational force that traps the atmosphere, holds the planet together, drives glaciers and rivers, and makes climbing what it isfun and challenging, yet sometimes frightening, perilous, and hard. Gravity lurks and lingers, always ready to pluck a climber from her tenuous stance. When a climber does fall, its up to the rope and anchors to catch her.

Climbing anchors allow us to safely defy gravity. We use them to build belay and rappel stations, set top ropes, and protect lead climbers. Solid anchors and proper rope techniques can prevent a fall from turning into a catastrophe; bad anchors are an accident waiting to happen.

Setting anchors is simple and straightforward on many climbs; on other routes, finding the anchors and engineering the protection system can be a significant part of the climbs challenge. For some climbers, the problem-solving aspect of creating anchors is one of the many appeals of rock climbing. For others, setting anchors is just a duty to keep the climbing safe. Either way, having a large repertoire of anchoring techniques makes climbing safer and more efficient.

This perspective is perhaps even more important now than it was when Craig first wrote it, because the number of people who need to learn the fundamentals of how climbing anchors work has grown exponentially since then, and most climbers today are introduced to the sport in the seemingly safe environment of the climbing gym. For this reason, one of the big additions to this second edition is a chapter on climbing gym anchors (see ). For experienced rock climbers, the concept of climbing gym anchors may seem like an oxymoron, but think again. In this book, anchor means anything that attaches a climber to the wall, regardless of whether the wall is made of rock, concrete, or plywood. This includes the bolts; natural protection; and top-rope, lower-off, or belay anchors. Gravity works the same in the gym as it does outside, and the forces of swinging falls and climber location relative to the anchors and the belayer are equally applicable to indoor and outdoor climbing.

Some of the ideas and techniques presented here come from the guides perspective; these are systems that are used day in, day out by thousands of guides around the world. Other information comes from the light-and-fast school, where speed, efficiency, and skill trump the urge to build big, complex belay anchors.

Many valid climbing styles, rope systems, and anchor-rigging techniques existthere are dozens of ways to crack an egg. This is where creativity meets science. There are a lot of options for building an anchor; in the end it needs to be strong enough for the given situation and convenient to use. The key is to understand the potential forces and build anchors that can handle the forces with strength to spare, all while constructing the anchors quickly, cleanly, and without using excessive gear.

On opposite extremes, a team of intermediate climbers may set as many anchors in a four-pitch route as a speed team does in twenty pitches. The speed climbers are cutting corners where they feel climbing skill can compensate for safety protocol, using advanced rope techniques and increasing risk tolerance in order to achieve their goal of climbing fast. This variation among climbing teams is fine because everyone is (hopefully) having fun and accomplishing their objectives without mishap.