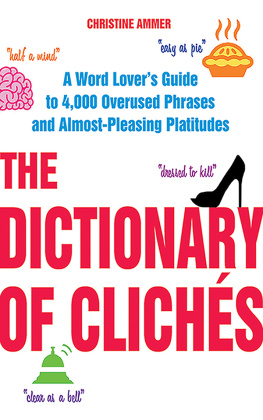

THE DICTIONARY OF

C lichs

THE DICTIONARY OF

C lichs

A W ord Lover's G uide to 4,000

O verused P hrases and

A lmost -P leasing P latitudes

Christine Ammer

Skyhorse Publishing

Copyright 2013 by Christine Ammer

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

eISBN: 978-1-62873-459-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-62636-011-2

Printed in the United States of America

C ontents

IN MEMORY OF DEAN S. AMMER

P reface to the New Edition

W hile new clich may seem like an oxymoron, our language is constantly changing; after all, how many folks knew about e-mail twenty-five years ago? And the same is true not only for individual words but also for the stock phrases we call clichs. Not only do new usages develop, but also some words and phrases die out. Thus, who today uses the phrase corporals guard for a small group of some kind, or the moving finger writes for the passage of time? Yet both terms appeared in a dictionary of clichs published a quarter of a century ago.

This revised and updated edition takes into account new usages and deletes some that are obsolete. I cant remember when I last heard (or saw in print) alas and alack, and surely blot ones copybook has died out along with ink-blotting and copy books. On the other hand, Ive included several hundred expressions that either qualify as clichs or are on the verge of becoming hackneyed. The business world is a rich source of new clichs, including such terms as Chinese wall, fork over, and go belly-up. Another rich source is the military, which gave us boot camp, break ranks, and double-barreled. Popular novels are rife with clichs, not so much in descriptive passages as in characters speeches. Elsewhere Ive described clichs as the fast food of language, and indeed, authors of popular fiction are recording language as it is actually spoken.

Apart from these sources, I rely on the fact that new expressions, especially those used by young people, give form to the particularity of an eras attitude. Among such expressions included in this edition for the first time are the somewhat sexist guy thing and girl thing, the onomatopoetic bling bling, and the dog ate my homework. Sports gave us also ran and hail Mary pass, environmental concerns carbon footprint, tree hugger, and gas guzzler, poker ante up, sweeten the pot, and show me the money. A couple of newer ones are so yesterday, for pass, and not so much, for a denial.

Clichs are an essential part of our everyday language, which keeps on changing. Hence this new edition.

Christine Ammer

Authors Note

T he 4,000 or so clichs in this dictionary include some of the most commonly used verbal formulas in our language. Some of them have been so overused that they set our teeth on edge (theres one!); have a nice day probably fits that category. Others are useful and picturesque shorthand that simplifies communication; an eye for an eye is one of those. In short, not all clichs are bad, and it is not the purpose of this book to persuade speakers and writers to avoid them altogether. Rather, it is to clarify their meaning, to describe their origin, and to illustrate their use. Indeed, clichs are fine, provided that the user is aware of using them. At the very least this book helps to identify them.

For etymology, for the derivation and history of these phrases, I have relied on the standard sources used by most lexicographers. Chief among them are the early proverb collections of John Heywood, James Howell, John Ray, Erasmus, and Thomas Fuller; the record of contemporary speech made by Jonathan Swift and the dictionaries of colloquialisms by Francis Grose; and that bible of modern etymology, the Oxford English Dictionary, which merits one of the few acronyms used in this book, OED. Other modern linguists whose work has been helpful include the late Ebenezer Cobham Brewer, Eric Partridge, John Ciardi, and William Safire, and the very much alive J. E. Lighter with his Historical Dictionary of American Slang.

For quotations I have relied on similar standard sources, principally Bartletts Familiar Quotations and the Oxford and Penguin dictionaries of quotations. To identify quotations from the Bible, I use the system 2:3, where 2 stands for the Bible chapter and 3 for the Bible verse. Unless otherwise noted, Bible references are to the King James Version (1611). For plays, it is 2.3 (for act and scene).

The entries are arranged in alphabetical order, letter by letter up to the comma in the case of inversion. Thus, if a comma is part of the main term (as in bell, book, and candle ), the entry is alphabetized as though there were no comma; if a comma is not part of the term (as in lean over backward, to), the alphabetization stops at the comma. Further, words in parentheses are disregarded for alphabetizing purposes; get (something) off ones chest is alphabetized as though it were get off ones chest.

Terms are listed under the initial article (a or the) only when it is an essential part of the term. For example, the pits is considered to begin with t but a pig in a poke is considered to begin with p. In phrases where a pronoun is implied, such as lick his chops or take her down a peg, I have substituted either one(s) or someone; thus it is lick ones chops and take someone down a peg. Numbers in figures, as in A-1, are treated as though written out (A-one). Alternate forms of a clich are indicated by a slash, as in make the best of it/a bad bargain. Where there are several phrases around a central word, the term is alphabetized under that word; to catch napping and to be caught napping are found under napping, to be caught/catch. In cases where a reader is likely to look up an alternative word, I have supplied cross-references, which are printed in small capitals (for example, see also on the fence.)

Because this system is admittedly imperfect, the reader who has difficulty locating a term is advised to look in the index at the back of the book.

I am deeply indebted to the many friends and acquaintances who have lent their assistance and expertise to this project. Among those who must be singled out are the late Albert H. Morehead, who first taught me the rudiments of lexicography; and my many librarian friends, with special thanks to the reference staff of Cary Memorial Library in Lexington, Massachusetts, who unstintingly gave their precious time to help track down elusive sources. The greatest debt is owed to my late husband, Dean S. Ammer, who patiently put up with countless interruptions and supplied the best intuitive knowledge of idiomatic speech that any clich collector could wish for. This book is vastly better owing to their help. Its errors and shortcomings are solely my own.