Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

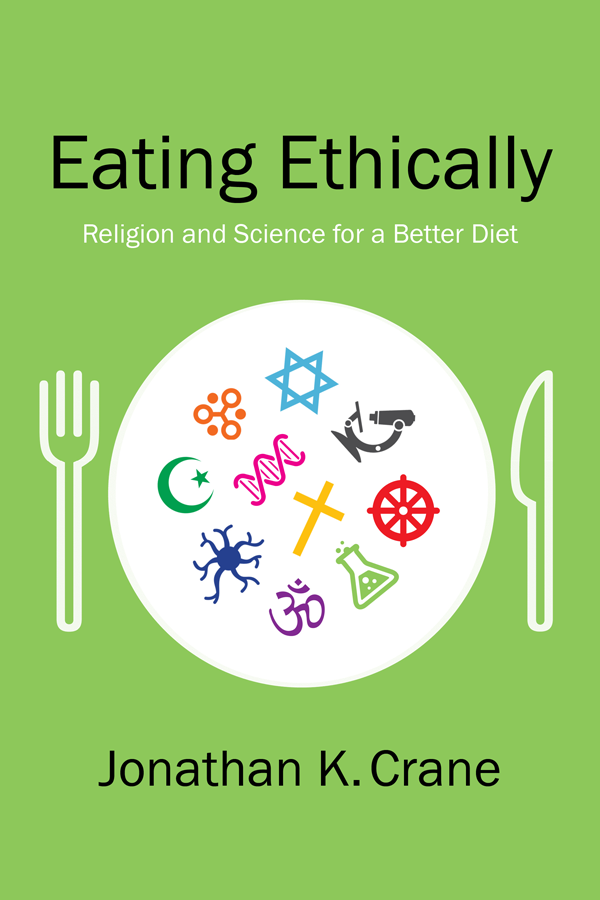

EATING ETHICALLY

JONATHAN K. CRANE

EATING ETHICALLY

Religion and Science for a Better Diet

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Jonathan K. Crane

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54587-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Crane, Jonathan K. (Jonathan Kadane), author.

Title: Eating ethically : religion and science for a better diet / Jonathan K. Crane.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017019389 (print) | LCCN 2017046619 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231173445 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Food consumptionMoral and ethical aspects. | FoodMoral and ethical aspects. | FoodReligious aspects.

Classification: LCC TX357 (ebook) | LCC TX357 .C68 2018 (print) | DDC 178dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019389

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

Cover images: Shutterstock

And know indeed that

what kind of a person is,

is determined at the table,

for there his qualities

are revealed and made known.

Bahya ben Asher ibn Halawa, Shulan Shel Arba (Second Gate) (12551340)

The Vulture eats between his meals

And thats the reason why

He very, very, rarely feels

As well as you and I.

His eye is dull, his head is bald,

His neck is growing thinner.

Oh! What a lesson for us all

To only eat at dinner.

Hilaire Belloc, More Beasts for Worse Children (1897)

CONTENTS

S everal years ago, I was looking around in the field of bioethics for discussions about eating-related ailments. I was surprised to find that, compared to other bioethical topics such as beginning- and end-of-life interventions, relatively little had been written on this one. This was true in the field of religious ethics, too. Curious about this gap in the conversation, I dug around in the tradition I know best: Judaism. I soon found a few classic resources suggesting that good health stems from eating well. I was not surprised, because that opinion is well known today. What did surprise me, though, was that the eating well these sources envision differed dramatically from the eating strategies I was more familiar with in the contemporary food environment. They inverted eatings orientation. Intrigued, I dug around some more and found that these were not isolated positions: other religious traditions encouraged similar eating strategies. Philosophers throughout history thought these strategies reasonable; and even contemporary physiology and the scientific study of eating corroborate these old ideas.

I pulled together some preliminary thoughts on these topics into an op-ed piece for the New York Times , which was published in March 2013 under the title The Talmud and Other Diet Books. That brief piece caught the eye of Patrick Fitzgerald, the editor at Columbia University Press, who called me with a simple query: Could this very brief column be made into a book? Ever since that initial conversation Patrick has been a stalwart enthusiast for this project, and for this I am extremely grateful.

I soon found myself reading in such fields as food studies, physiology, satiety studies, religious history (of food), philosophy (of food), cultural studies, medicine, and more. I also observed that dramatic shifts in attitudes toward food and practices in eating were occurring in society generally. A veritable explosion of interest in all things food has happened: just think of the incredible growth of food-centered TV shows and channels, documentaries, book-length journalistic investigations, food clubs, community-supported agriculture, sustainable and organic restaurants, and more that have emerged in the past few years.

I offered an undergraduate class at Emory University on the topic; it was overenrolled. Encouraged, the next year I flipped the classroom so that we were in a kitchen: the students were to plan menus, shop for food, and prep, cook, and serve meals based on weekly themes. By turning the academy on its head, we literally ate our subject matter, whether commodity crops or farmers markets produce, whether from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or religious consumptive rituals. That class had a waiting list of over fifty students. When I offered that class again the next year, any student at Emory could take it. Nearly 150 students from every school in the university applied for the twenty spots. I was fortunate to collaborate on those courses with incredible colleagues from across the university: Amy Webb Girard, Mindy Goldstein, Peggy Barlett, Laurence Sperling, Sam Sober, Linda Craighead, Jennifer Frediani, Simona Muratore, Craig Hadley, and Peter Thule, among others. Their wisdom has been invaluable to this project.

Interest in this intersection of food and eating-related ethics, religion, and science has been palpable off campus, too. Over the past several years, various communities around North America have asked me to present on these topics. This project has benefited from the insights, questions, and provocations of audiences at St. Johns University, University of St. Thomas, Case Western Reserve University, Mercer University, Georgia Institute of Technology, the Judaism, Science and Medicine Group, the American Society of Bioethics and Humanities, the Commission on Social Action of Reform Judaism, the Chicago Board of Rabbis, Religious Action Center, Temple Beth Am of Seattle, Yom Limmud in Houston, and Congregation Shearith Israel in Atlanta.

I emerged from these conversations convinced that this project should not be merely academic. While of course it should be grounded in solid research, I wanted it to reach a larger audience. I have thus written it for keen readers interested in appreciating the intertwining of religion, science, and philosophy in relation to eating and food. Citations are set at the end so the book may be read without distraction; the bibliography suggests further reading. Even as the book makes a cumulative argument, individual chapters are more or less freestanding units. Its many visuals either augment or are integral to the story.

From the books earliest inception, the faculty, staff, and students at the Center for Ethics at Emory University have been exceptional colleagues, mentors, interlocutors, and, most important, commensal partners. Without them, I could not have developed the ideas or carved out the time to build this project and its related courses.

Closer to home, I am thankful to Dancing Goats, our neighborhood caffeine dispensary, where stimulating conversations were never lacking and where I wrote substantial portions of this book. Through the years I had many fruitful conversations with David Goldstein, Leah Garces and Ben Lopman, Aaron Gross, Janine Franco and Alan Pinstein, Jaci and Jon Effron, Mike and Dana Geller, Lisa and Moses Staimez, Charles and Nola Miller, Barbara and Peter Cohen. My wife, Lindy, and our sonsNadav, Amitai, and Rafaelare my constant and beloved table partners, always ready for cooking up and enjoying a tasty meal.