1.2 Agricultural Development and Global Food Security

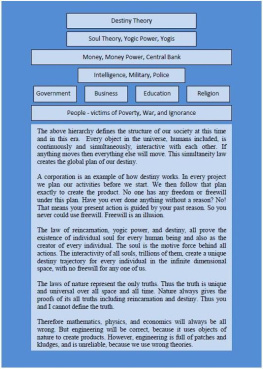

Food is one of the basic needs of human being. The bulk of the food consumed in the world are procured from a very limited number of crop species. Today by and large, 2530 food-yielding species supply food to mankind, viz. wheat, rice, maize, barley, oats, sorghum, millets, soybean, bean, pea, chickpea, peanut, banana, citrus, tomato, sugarcane, cassava, potato, sweet potato, yams and five oil seed types and a few beverages (Harlan ), of which only three crop types, viz. rice, wheat and maize, supply 60% of food requirements for the world human population. Though over 7000 species either partly or fully domesticated have been used so far from time to time for food production, today only 30 species are bearing the herculean responsibility of providing 95% of the huge world food requirements. Many of the neglected and underutilised species are of great significance as a source of food in low-income food-deficient countries (LIFDCs). They are extremely important because of their wide adaptability to the marginal areas and contribution of a significant part of the local diet with useful nutritional supplements. In comparison with major crops, these neglected and underutilised species require relatively low input and therefore help in sustaining agricultural production. These regional traditional crops are often low yielding and are not competitive to conventional major crops, even though many of them have the potential to become economically viable. Very often narrow genetic diversities in important agronomic traits as well as lack of genetic improvements prevent the development of these crops. Other constrains include lack of adequate knowledge on the taxonomic delimitation, the genetics of agronomic and quality traits and reproductive biology.

Many plant species with significant food and/or industrial value are yet to be utilised properly due to lack of appropriate and adequate programmes for their evaluation and development and remained underutilised. Some of them have been so neglected and erosion of their gene pool is so severe that they are often considered as lost crops. A vast majority of these plants have the capability to meet the increasing demand for food and nutrition, healthcare, medicine and industrial needs. Many of these species are involved in traditional localised farming especially in marginal remote areas, and quite often these crops act as life-savers for millions of poor people in the regions where food security and malnutrition are a problem. The rural community knows very well the cultivation practices of the underutilised crops and prepare food from them and use them in their daily life, for health care, shelter, forage and fuel particularly during drought, famine and the dry seasons (Campbell ). These crops include cereal, pseudocereals, fruits and nuts, pulses, vegetables, root and tubers, oilseeds and other industrial, forage and fodder species.

Global food security and economic growth is certainly going to face a stiff challenge in the coming few decades due to population outburst especially in the developing and Third World countries. In an estimate it appears that nearly 1.2 billion people in the world are not lucky enough to get adequate food to meet their daily nutritional requirement and a further 2 billion people are deficient in one or more micronutrients (Azam-Ali and Battcock ).

An autonomous international scientific organisation, International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI), was established by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) in 1994, and it is situated in Rome, Italy, at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The prime role of IPGRI is to monitor research activity and to promote and coordinate an international network of plant genetic resource, germplasm management conservation, evaluation, documentation and utilisation of useful plant germplasm globally and also the collection and exchange of plant genetic resources. The functioning of IPGRI and other such institutes is monitored by CGIAR which was established in 1972. The joint efforts of Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Bank and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) resulted in the creation of CGIAR to establish international research institutes and subsequently to look after their progress.

Global food security and economic growth is now being threatened by declining number of plant species. This decline has placed the future supply of food and rural income at risk. IPGRI has succeeded in promoting greater awareness regarding the important role that minor crops can play in securing and safeguarding the livelihood of people all over the world. Ethnobotanical surveys confirm the presence of hundred of such crops in many countries and different remote corners of the globe that represent a plentiful treasure of agro-biodiversity. Such underutilised mainly ethnic crops can play a vital role to improve income, food security and nutrition. The development of agriculture and food security depends partly on our ability to extend the agricultural species range in an effective and sustainable manner. This requires finding of ways and means to protect and enhance cultivation of the locally important species so that they can be employed more widely in agriculture and environment management and finding of ways to explore the use of local crops in order to tap the hidden potential contained in them. Today global food security has become increasingly dependent on few conventional crops causing their over-exploitation. Even if mankind has used more than 10,000 edible species since the prehistoric period, today only 150 plant species are commercialised globally in a significant scale, 12 of which are supposed to provide approximately 80% dietary energy from plants and only four plant types, viz. rice, wheat, maize and potato are supposed to supply over 60% of the global requirements for protein and calories. Moreover the gradual decrease of the crop varieties are increasingly threatening the future supply of food and rural income and this has compelled research organisations and scientists worldwide to retrieve, research and disseminate the knowledge regarding production and utilization of neglected, underutilised new plant species or the so-called alternative crop (FAO ).