1. The Short, Yet Surprisingly Long History of the Hubble Space Telescope

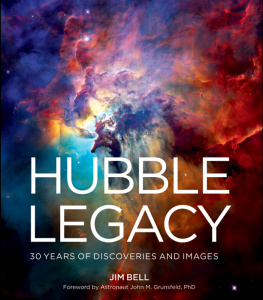

Space Shuttle Discovery stood on Launch Pad 39B at Kennedy Space Center on April 24, 1990, poised to carry and deliver its most important scientific payload. Shuttle mission STS-31, with Mission Commander Loren J. Shriver, Pilot and future NASA Administrator Charles F. Bolden Jr., and Mission Specialists Steven A. Hawley, Bruce McCandless II, and Kathryn D. Sullivan, was assigned the primary mission of deploying the Hubble Space Telescope into a 380 mile orbit above the Earth.

At 8:33:51 EDT, the Shuttle Discovery lifted off on its historic mission of placing into orbit what has become one of the most famous telescopes in history, one that has produced scientific discoveries and captured the imaginations of this era. The Hubble Space Telescope, or HST for short, got off to a somewhat rocky start after its insertion into orbit. But the HST has since proved to be one of the most productive scientific instruments in history.

To the public, this launch was the beginning. But, in truth, the beginning occurred years earlier. In fact, decades earlier.

The concept of a telescope in space was first described in 1923 by Hermann Oberth. Oberth was an Austro-Hungarian born doctoral candidate, who published Die Rakete zu den Planetenrumen (The Rocket to Planetary Space) in which he suggested a telescope could go into space aboard a rocket. Oberth would become a well regarded pioneering German rocket scientist whose pupils included Dr. Wernher von Braun. Both Oberth and von Braun would immigrate to the United States and work on the US space program. The idea of a telescope in space came up again in a paper entitled Astronomical advantages of an extraterrestrial observatory published in 1946 by accomplished astrophysicist Lyman Spitzer Jr. Part of Spitzers rationale for a space-based telescope included the fact that an instrument placed above Earths atmosphere would be freed of atmospheric transparency limitations in the visual spectrum, and the platform could also carry out observations at the infrared and ultraviolet portions of the spectrum that are otherwise blocked by Earths atmosphere and magnetosphere. By 1962, a space telescope concept like the Hubble was being developed. Spitzer served as an advocate for space borne observatory platforms, such as the Orbiting Astronomical Observatory (OAO) satellite, by pushing the U.S. Congress and the scientific community for support. With his track record of high achievement, Spitzer was among those who persuaded Congress in 1969 to approve the idea of building a large space telescope.

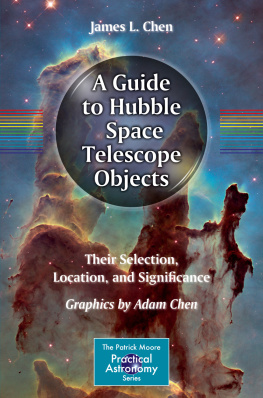

NASA began preliminary studies in 1975, and the Hubble Space Telescope project was funded by Congress and built between 1977 and 1985. The Hubble Space Telescope was built by NASA with contributions from the European Space Agency. The fabrication of the instrument was managed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, with the critical mirror optics made by the Perkin-Elmer Corporation.

Work began on the mirror in 1979, with completion in late 1981. The task of grinding and figuring the 2.4 m primary mirror was given to the Perkin-Elmer Corporation.

The HST optical design is a Ritchey-Chrtien variant of the Cassegrain reflecting telescope. This design gives a wide field of view with excellent image quality across the field. In fact the Ritchey-Chrtien design is now used by the majority of modern large optical telescopes. The designs only disadvantage is that the primary and secondary mirrors are hyperbolic in shape and thus are difficult to fabricate and test.

As the HST is designed to be used at ultraviolet, visible, and infrared wavelengths, the telescope had to achieve the desired diffraction limited optics. This meant that its mirror needed to be polished to an accuracy of 10 nm, or about 1/65 of the wavelength of red light.

Construction of the Perkin-Elmer mirror began in 1979, using Corning ultra-low expansion glass. To minimize weight, it consisted of inch-thick top and bottom plates sandwiching a honeycomb lattice. The mirror polishing was completed in 1981 and it was then washed using hot, deionized water before received a reflective coating of aluminum under a protective coating of magnesium fluoride.

The seeds of the Hubble optical problems were sown because of the stringent optical requirements and funding pressures. Schedule delays and cost growth of the Hubble program caused both the contractor and government agency to look for areas to reel in the schedule and reduce cost growth. As a result, an over-reliance on a single test devise spelled trouble for the HST. A testing device called a null corrector had been incorrectly assembled, with one of its lenses assembled out of position by 1.3 mm. During the initial grinding and polishing of the mirror, Perkin-Elmer analyzed the mirrors surface with two conventional null correctors. During the final figuring step, Perkin-Elmer opticians switched to the custom-built null corrector, designed explicitly to meet very strict tolerances. With this custom null corrector assembled incorrectly, the mirror was extremely precise, but shaped to the wrong curve. There was one final opportunity to catch the error, since a few of the final tests needed to use conventional null correctors for various technical reasons. These tests correctly indicated that the mirror suffered from spherical aberration, with the perimeter of the mirror being too flat by about 2,200 nm. But both Perkin-Elmer and NASA relied on the custom-built null corrector results based on the assumption of its greater precision, and to save both time and money. Thus the flaw remained during final assembly of the Hubble spacecraft.

The tragic loss of the Space Shuttle Challenger on 28 January 1986 caused the Space Shuttle program to be suspended. The suspension caused the HST to be stored and maintained by Lockheed in California, at the cost of $6 million per year. From its original total cost estimate of about $400 million, the telescope had suffered a cost growth of over $2.5 billion to construct. The cost growth can be attributed to the difficulty of estimating the costs of building something that had never been built before, and the storage cost after the Challenger mishap.

Space Shuttle Discovery stood on Launch Pad 39B at Kennedy Space Center on April 24, 1990. The countdown was briefly halted at T-31 seconds when Discoverys computers failed to shut down a fuel valve line on ground support equipment. Engineers ordered the valve closed and the countdown continued. And at 8:33:51 EDT, Discovery lifted off on its mission to carry the Hubble Space Telescope into orbit.

To deploy HST into an orbit that provided a long service life, Discovery rocketed to a record 370 miles. The deployment of the Hubble was not without some technical problems. One of the HSTs solar arrays failed to completely unfurl. While NASA ground controllers searched for a way to command HST to complete the unfurling of the solar array, Mission Specialists McCandless and Sullivan began preparing for a contingency extravehicular spacewalk in the event that the array could not be deployed by ground control. The array eventually came free and unfurled through ground control commands. Astronaut Hawley, controlling the Remote Manipulator System arm, then deftly plucked the massive Hubble out of the shuttle cargo bay and deployed it in orbit.

During the initial tests of the optical system after the launch of the telescope, it became obvious that there was a serious problem with the optical system. Stellar images which should have been approximately 0.1 arc sec across were more than 1 arc sec acrossbasically equivalent to those of ground based telescope images. On 27 June 1990, some 2 months after HST was placed in orbit, Dr. Edward Weiler, Chief Scientist for the Hubble Space Telescope announced to the public in clear terms: Its broken and were going to have to fix it .