Watching the Universe!

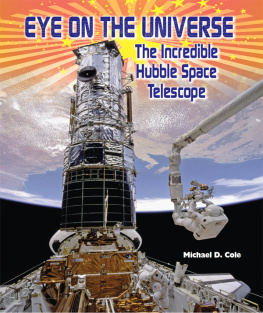

Would you like to see a colossal storm on the planet Saturn? Or would you rather see the black hole at the center of our Milky Way galaxy? Is it possible to see a planet in another galaxy 13 billion light years away? Orbiting high above Earth, the Hubble Telescope captures all these amazing wonders of space. Incredible photographs are relayed back to Earth, allowing scientists and astronomers to study parts of space that were once completely unknown. Author Michael D. Cole explores the remarkable journey of launching this telescope into space and how it has unlocked many of the greatest mysteries in the universe.

About the Author

Michael D. Cole is a graduate of Ohio State University and has written several titles for Enslow Publishers, Inc., including Unsinkable!:The Titanic Shipwreck.

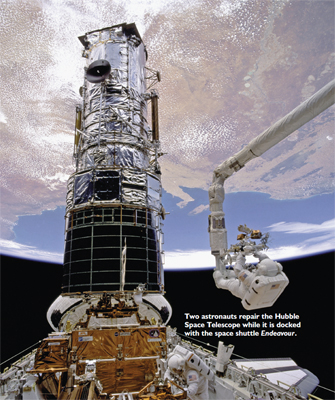

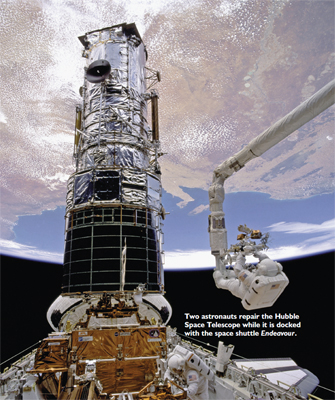

Image Credit: NASA Johnson Space Center

The Hubble Space Telescope was carefully loaded into the payload bay of the space shuttle Discovery. Astronomers, engineers, and other scientists had spent fifteen years designing and building the mighty telescope. At long last, it was ready for its journey into space. In the middle of April 1990, Discovery and its long-awaited cargo rolled slowly to the launchpad at Cape Canaveral, Florida.

The giant telescope had cost more than $1.6 billion! Scientists had faced many problems in constructing the telescope. Most of them believed their years of difficult effort were worth it. If the telescope worked, it would be the most powerful telescope ever built.

Finally, the day for which these scientists had long been waiting had arrived. Discovery sat on the launchpad with the Hubble Space Telescope inside, ready for its historic ride into space.

As the countdown continued, those who had worked on the telescope watched and listened. If all went well, Discoverys crew of astronauts would release the telescope into orbit the following day. Strapped to their seats, the astronauts listened to the countdown on their helmet headsets.

T minus one minute and counting...

Like the thousands of people who had worked on the telescope, the astronauts braced themselves for the approaching moment of liftoff.

The final seconds ticked down.

Five... four... three... two... one...

Orange fire and huge clouds of smoke gushed outward from Discoverys engines. The tremendous thrust lifted the space shuttle off the launchpad.

... And liftoff of the space shuttle Discovery, the NASA announcer said, with the Hubble Space Telescopeour window on the universe.

Discovery roared through the sky toward space. As it climbed higher and higher, the solid rocket boosters and the external fuel tank separated from the shuttle. Minutes later, the shuttle was in orbit.

The next day, Discoverys crew opened the payload bay doors. The Hubble Space Telescope, named after American astronomer Edwin Hubble, was then released into orbit around Earth.

It was more than three weeks before the telescopes instruments were ready to look at their first object in space. After all the waiting, astronomers had high hopes for this amazing machine.

Astronomers had long wanted a telescope in space. The biggest reason for such a telescope was simple: All light from space that reaches a telescope on the ground is blurred by Earths atmosphere. A telescope in space, above Earths atmosphere, would be able to see objects in space much more clearly. Without the blurring effect of Earths atmosphere, it would also be able to see much farther out into space.

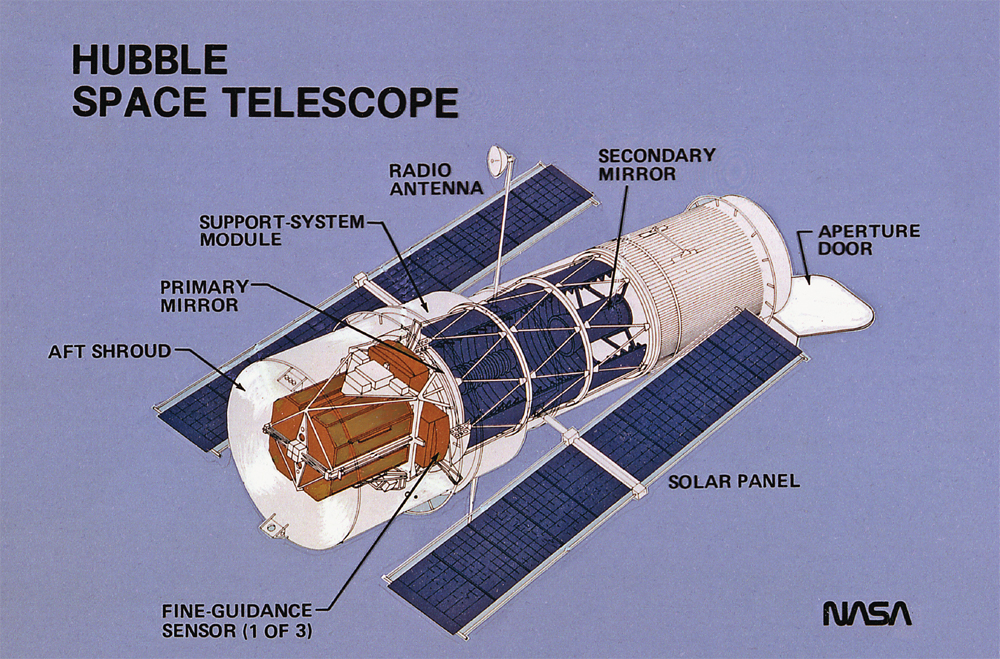

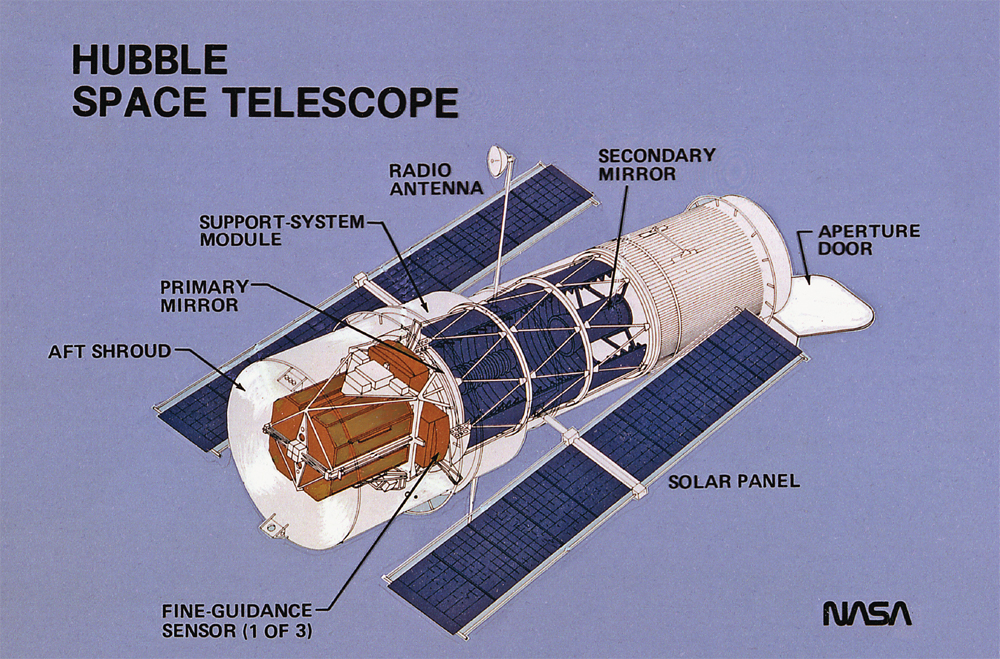

The most important part of the Hubble Space Telescope was an eight-foot-wide mirror. This primary mirror was designed to focus on distant objects in the universe like never before. Light from a distant star or galaxy would reflect off this large mirror and onto a series of smaller mirrors, bouncing the light into what was called the Wide Field Planetary Camera, or WF/PC. Because of this abbreviation, everyone called the camera the wiff pic.

Image Credit: NASA Kennedy Space Center

Discovery lifts off from the launchpad at Cape Canaveral, Florida, on April 24, 1990, carrying the Hubble Space Telescope in its payload bay.

The WF/PC records the objects image and stores it in a computer. The computer then relays the image to the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, where a team of astronomers studies it.

Many highly complex scientific instruments for measuring the mirrors reflected light were placed aboard the Hubble Space Telescope. The Faint-Object Camera was designed to take pictures of dim objects in space that can barely be seen from Earth. The Faint-Object Spectrograph would examine the different colors of light coming from these objects. By this method, scientists could learn the objects temperature, as well as its chemical and gas makeup. The brightness of light coming from a star or galaxy would be measured by the High-Speed Photometer. This measurement would help astronomers learn about the size of the object in space, as well as its distance from Earth.

While the Hubble Space Telescope is a telescope, it is also a spacecraft. It is powered by a set of solar arrays attached to either side of the telescope. Its guidance system is used to point the telescope in the direction of the object scientists wish to view. This system is very important. The many powerful instruments aboard the Hubble would be useless if scientists were unable to aim and focus the telescope effectively.

Image Credit: NASA Marshall Space Flight Center

Hubble, shown in this diagram, is not only a telescope, but also a spacecraft. Its guidance system allows scientists to point the telescope at objects they wish to view.

By May 20, 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope was ready to be aimed at its first target in space. The engineers, astronomers, and other scientists involved with the project believed the telescopes systems were ready for operation. Hundreds of these scientists gathered in control rooms at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland; the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama; and the Space Telescope Science Institute.

Reporters from newspapers and radio and television stations were there with the scientists to watch the first images from the new telescope. The press had carried many stories about the telescope during all the years it was being built. The publics expectations for the telescope were high.

Controllers at the Goddard Space Flight Center sent a set of commands to the telescope. Orbiting 375 miles above Earth, the telescope responded, turning slowly to catch the light from a star cluster 1,300 light-years away. It was the star cluster NGC 3532.

The light from the distant star cluster hit the primary mirror, bounced up to the smaller secondary mirror, and traveled back through the central opening in the primary mirror. The twice-reflected light then bounced off another mirror and into the WF/PC, which recorded the image. All was going according to plan.

The scientists who had gathered at the three centers knew the telescope had received its aiming commands. For several minutes, all of them waited anxiously for the image to appear on their computer screens.