Chapter One

BOLD HUNT FOR DISTANT GALAXIES

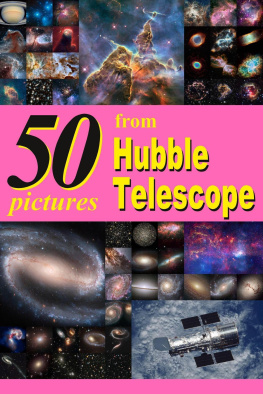

Astronomer Bob Williams and his scientific team prepared to take a big risk in December 1995, a risk that could have ended Williams distinguished career as a scientist. It involved taking a series of photographs. Williams was keenly aware that there was great power in certain photos. Still fresh in his mind was the Blue Marble a magnificent portrait of Earth taken from high above by U.S. astronauts in 1972. It had caught the attention of people around the globe, showing that they lived on a tiny, fragile sphere floating in the vastness of space.

Apollo 17 astronauts snapped a photo of Earth in 1972 that became known as the Blue Marble.

Williams wanted to capture a very different sort of image one of an area of space extremely far away from our planet. Two years before, he had become director of the objects so distant that they appeared dim and blurry from ground-based telescopes.

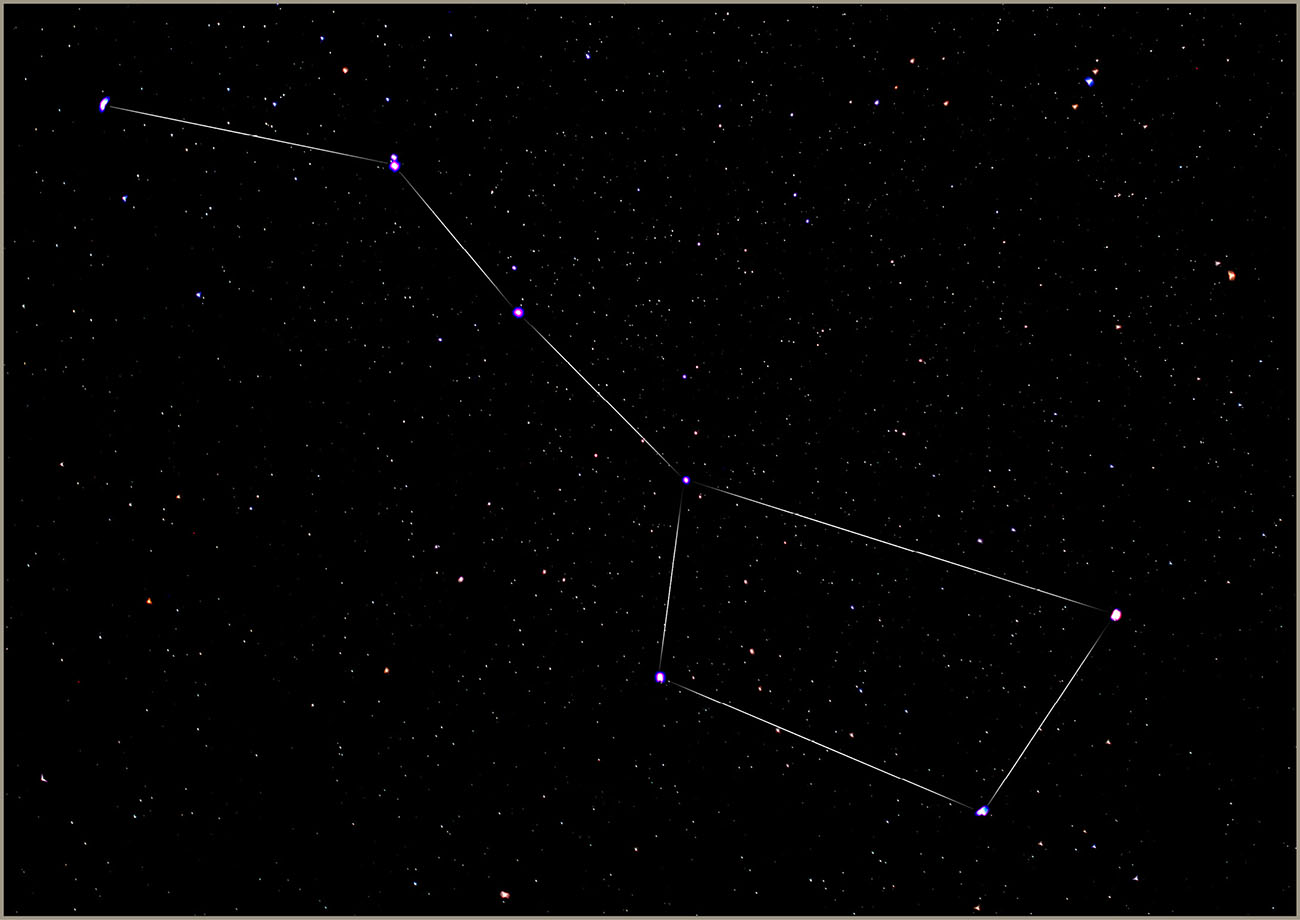

Williams wanted to point Hubble at a tiny patch of sky near the handle of the Big Dipper, in the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The patch covers an area as big as a grain of sand held at arms length. The plan was to take hundreds of pictures of the target area during 10 days. Sophisticated computer software would combine them into a single image.

The goal was almost too ambitious to imagine. Williams and his team wanted to test the outer limits of space and time. We know that the Milky Way. Many other galaxies exist beyond the Milky Way. Hundreds of thousands of these massive systems were detected and photographed in the 20th century.

The Milky Way galaxy, which contains our solar system, fills the night sky.

But astronomers had yet to determine how far into the reaches of deep space galaxies existed. They also wondered when the first galaxies appeared. Have they always looked like they do today, or have their shapes evolved over time? And will they, along with the Williams and his team hoped that photographing some very distant galaxies might allow them to begin to answer some of these questions.

Hubbles camera pointed near the handle of the Big Dipper, a star pattern in the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear.

Using Earth-based telescopes, that little piece of space in Ursa Major appeared to be mostly black and empty of cosmic objects. It contained a few stars known to be in one of the Milky Ways outer arms. Telescopes had also detected a handful of tiny, blurry blobs of light in the target region, which might be galaxies. But if so, there were not many of them. Otherwise, the area Williams had singled out seemed to be composed mostly of empty space.

Considering these facts, several of Williams fellow astronomers felt that devoting 10 days of Hubbles time to such a venture might be a serious mistake. There was wide agreement that every minute of Hubbles time was scientifically valuable, even precious. What if, after the 10 days, Williams proposed photo showed mostly empty space?

Further complicating matters was the fact that Hubble already had gained a reputation for not living up to expectations. Not long after the telescopes launch, its first photos had been a disappointment. An unexpected flaw in its mirror had caused the pictures to be blurry.

Astronauts repaired Hubbles faulty mirror in December 1993.

A group of astronauts from the space shuttle he cordially asked.

PICKING THE PATCH

Some technical problems had to be overcome in order to take the Hubble Deep Field (HDF) photograph. One was getting around the many stars and other objects in the Milky Way in order to see galaxies lying far outside our local galaxy. Bob Williams and the other scientists who helped him take the HDF solved this problem by choosing a tiny patch of sky in the constellation Ursa Major. Because of the location, only a handful of stars inside the Milky Way would block the view of deep space.

exposure photos from a space platform moving at high speeds. As Earth travels around the sun, views from the planet of various objects in space are constantly changing. Because Hubble is in Earths orbit, whatever spot in the sky it sees also appears to be constantly and quickly changing position.

How, then, could astronomers keep Hubbles onboard camera focused on a spot long enough to take a long-exposure picture? NASA scientists overcame this challenge by developing sophisticated computer

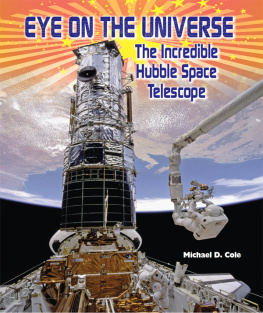

The Hubble Space Telescope floats gracefully above Earth.

But regardless of how many other scientists cautioned Williams, he continued on. He believed that the proposed photo would reveal at least some galaxies. Now that Hubbles optics were as good as new, he reasoned, they might be able to pick up the light of faint galaxies.

In fact, bursting with a spirit of exploratory zeal, Williams was willing to go full speed ahead no matter what the consequences might be.

Before and after photos of the galaxy M100 show the dramatic improvement in the Hubble Space Telescopes view of the universe after the 1993 repair mission.

There was another reason that Williams felt comfortable moving forward with his bold hunt for distant galaxies. As director of the

So Williams and his team began preparing in earnest to aim Hubbles great orbiting eye at a tiny piece of dark sky in the of up to 40 minutes. Simple math revealed that this would tie up Hubble for quite a number of its revolutions around the planet roughly 150 orbits in all.

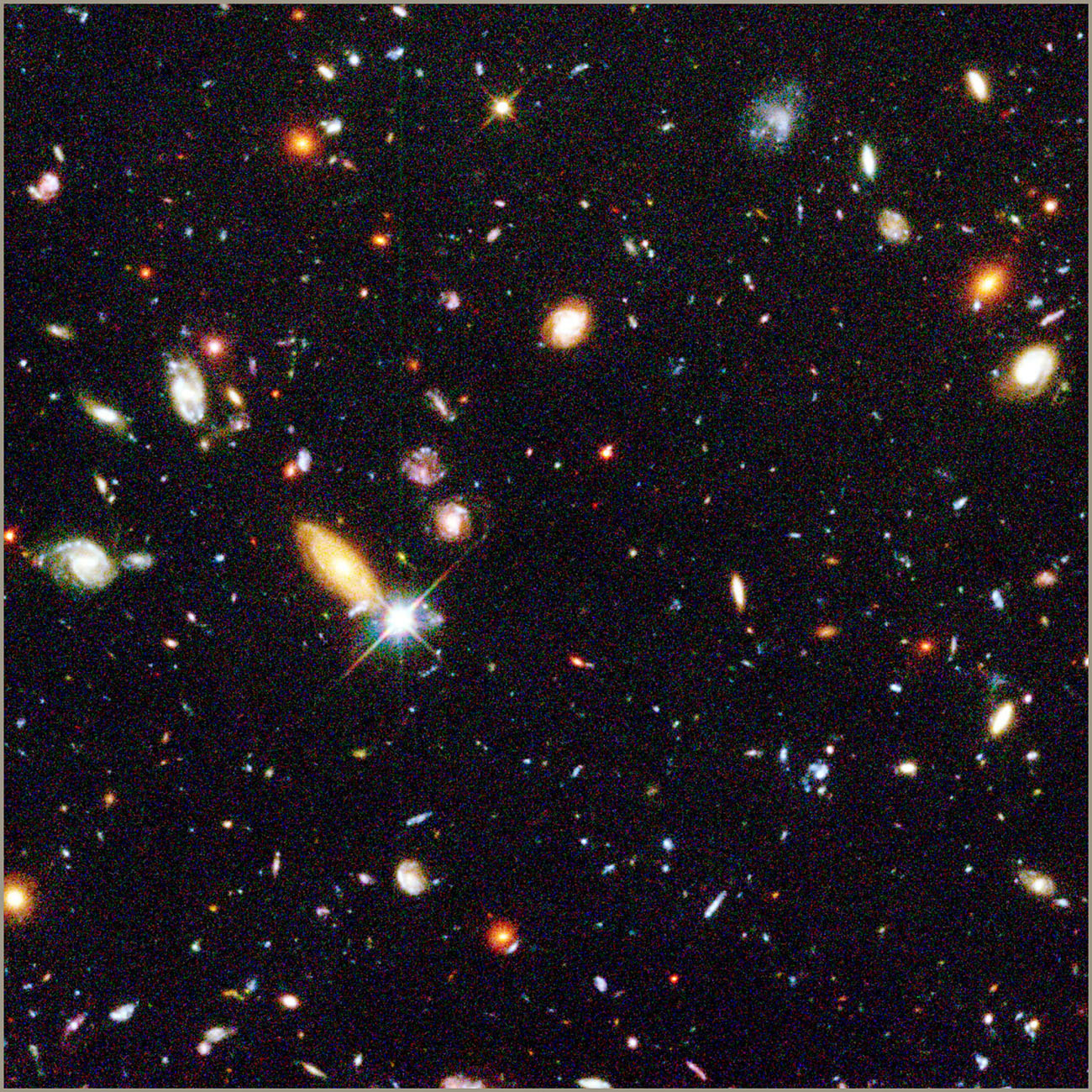

When Hubbles onboard camera began taking the photos on December 18, 1995, Williams and his associates wondered whether the images would show anything significant. If they did not, the public would likely never hear about this astronomical experiment. And Bob Williams might thereafter be known among scientists as learned and well-meaning, but largely a dreamer. No one involved foresaw the immense significance of what they were creating. One scientist later said that viewing the result of their efforts the photo known as the Hubble Deep Field was profound. It was, he added,

The Hubble Deep Field photo revealed galaxies never seen before.

Chapter Two

TO THE EDGE OF THE UNIVERSE