Copyright 2006 Patrick Brighton

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by Menasha Ridge Press

Distributed by Publishers Group West

First edition, first printing

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brighton, Patrick, 1962

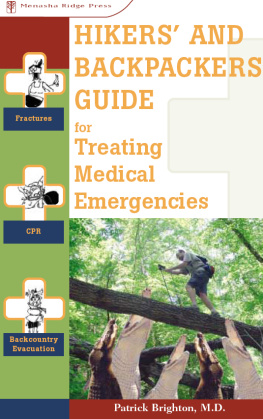

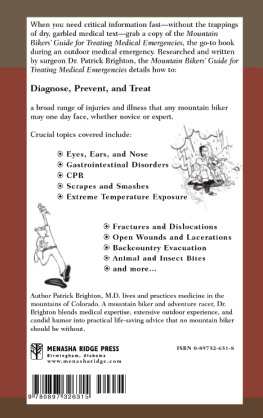

Hikers and backpackers guide for treating medical emergencies / Patrick Brighton.1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-89732-640-7

1. Hiking injuries. 2. Backpacking injuries. 3. First aid in illness and injury. 4. Medical emergencies. I. Title.

RC88.9.H55B75 2005

616.025dc22

2005049634

Illustrations by Tami Knight

Text design by Clare Minges

Cover design by Travis Bryant

Menasha Ridge Press

P.O. Box 43673

Birmingham, AL 35243

www.menasharidge.com

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dont you love it when the Academy Award winners launch into a 30-minute sermon in which they thank everyone from the person who cuts the hair around their poodles butt to Aunt Marthas financial adviser?

There are, however, a number of people who made this work possible, so if you enjoy any portion of it, send your thanks to them. Firstly, Bob Sehlinger at Menasha Ridge Press, who called me out of the blue and said, Why dont you get off your tokhes and do something constructive? Thats paraphrased, by the way. Also, I thank Russell Helms, Molly Merkle, and the rest of the wonderful Menasha Ridge staff. Next, Tami Knight, who has been kind enough to share with us her unsurpassed wit and insight through her illustrations.

Finally, I would like to say thank you to the person who has been my constant companion for the last ten years and who has truly shown me what it means to be able to enjoy a peaceful, balanced lifemy dear wife, Kimberley.

INTRODUCTION

Outdoor medical handbooks bear the burden of reducing an astronomical (and frequently controversial) volume of knowledge into a few brief (one hopes), useful pages. To further complicate the issue, these books are most useful during an actual emergency, when the reader of said book tries to locate this useful information in the throes of a medical crisis involving himself or a companion.

Bearing these facts in mind, I have attempted to produce a manual that those in medical-crisis situations find easy to use when they themselves are suffering from adrenaline-induced brain lock and are shaking like a Mr. Potato Head in the hands of a hyperactive 3-year-old. This simplistic presentation may make some medical personnel scoff (has anyone actually seen someone scoff?). However, even as a board-certified surgeon with extensive trauma experience, I have found myself hesitating momentarily in the backcountry during medical crises involving a close friend or family member. Another point is this: what a person with a certain medical expertise might do, and what a person with little or no medical experience might do frequently differ. This book is primarily geared toward persons in the latter category. So to all you medical personnel nitpickers, I say ttttthhhhhhhhttt!!!

The fact is, things are different when we find ourselves outside our asphalt-infested, sterile, citified lives and suddenly our wife or son is bitten by a rattlesnake or falls and breaks a leg and we are miles from help, and darkness and a storm are closing in.

The one thing that has served me well in hundreds of life-threatening situations through the years is remembering to relax! Sounds easy, right? Wrong! But it is vitally important to do so during a crisis. There are several things to bear in mind:

(1) Whatever events led up to the current emergency are now irrelevant. If preventable things happened (and they usually did), beat yourself up later, not now.

(2) KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid). This is never truer than during a medical emergency. No handbook (not even this one) or even complete trauma textbook can prepare you for every emergency, so use your common sense first and foremost.

(3) Following from the above instruction: consider what a very wise professor told me when I was an intern: No one ever died in five seconds. Unless you are actively rescuing someone from a dire situation (e.g., drowning, bear attack, etc.), you always have time to think. As it has for hundreds of thousands of years, the mind remains the most valuable asset of the biped. If a companion is injured, especially severely, you must take some deep breaths and think logically. If someone actually will die in five seconds, there is almost certainly nothing you can do about it anyway, as morbid as that sounds. However, if you do something rash, especially right after an emergency occurs, you can turn a salvageable situation into a hopeless one.

I sometimes diverge from the usual dogma to interject some appropriate humor (at least I think its appropriate) into this text. This is important: an entertained reader, instead of daydreaming about the beauty of a lonesome lake in the Wind River range, might find this book amusing enough to focus her or his attention on learning how to dislodge the partially rehydrated macaroni from a partners larynx and thereby save a life. If you are reading this manual, you already understand how wonderful backcountry travel is. You probably also have at least considered that harm might befall you or a companion while in the backcountry. Therefore, it would make some sense to anticipate as many potentially harmful scenarios as possible. (Go ahead and avoid those scenarios if you can.) In short, be prepared. Really, Im not kidding: be prepared for possible medical emergencies.

Most situations present obvious dos and donts; for example, dont walk up to the edge of a cliff, dont French kiss a Gila monster, do make sure you can run faster than your buddy in case of a bear attack. Some dos and donts are subtler. A few helpful and maybe not-so-obvious ones will be included in each chapter.

Given the constraints of space, this manual could not come close to being complete; however, should you notice some glaring omission, please feel free to contact me. Along those lines (disclaimer!), medical emergencies are just thatemergencies. Unfortunately, things dont always turn out as well as we would like. The information presented here should in no way be considered definitive. Outcomes following medical emergencies depend on many factors, including the skill of the treating person, the underlying condition of the patient, the available resources, the ease of obtaining definitive medical care, the phase of the moon, and so on. This information represents only what I would anticipate I would do given a certain emergency situation.

Sally forth and enjoy the backcountry safely!

MEDICATIONS

Dispensing

Medicationschemicals synthesized from raw materials ruthlessly extracted from our rapidly vanishing rain forests only to enhance our already pathetically easy existence wait a minute, wrong speech. Anyway, medications really are beneficialeven essential in certain emergencies in outdoor settings. Most medications are administered orally ( per os, for you Latin speakers). However, certain medications can be administered only by injection, either into a muscle or vein, and still others are given via inhalation, through patches applied to the skin, or by insertion into the rectum (wait a minute, I dont think I know you that well). Most medications are given orallyibuprofen, Claritin, and so onand we are all familiar with taking medications this way. In a medical emergency, however, the victim may not be conscious, may have an obstructed airway, or may not be able to otherwise swallow medications. Do not ever attempt to give a victim medications by mouth under these circumstances or if you have any concern that a pill may end up in his airway instead of his stomach.

Next page