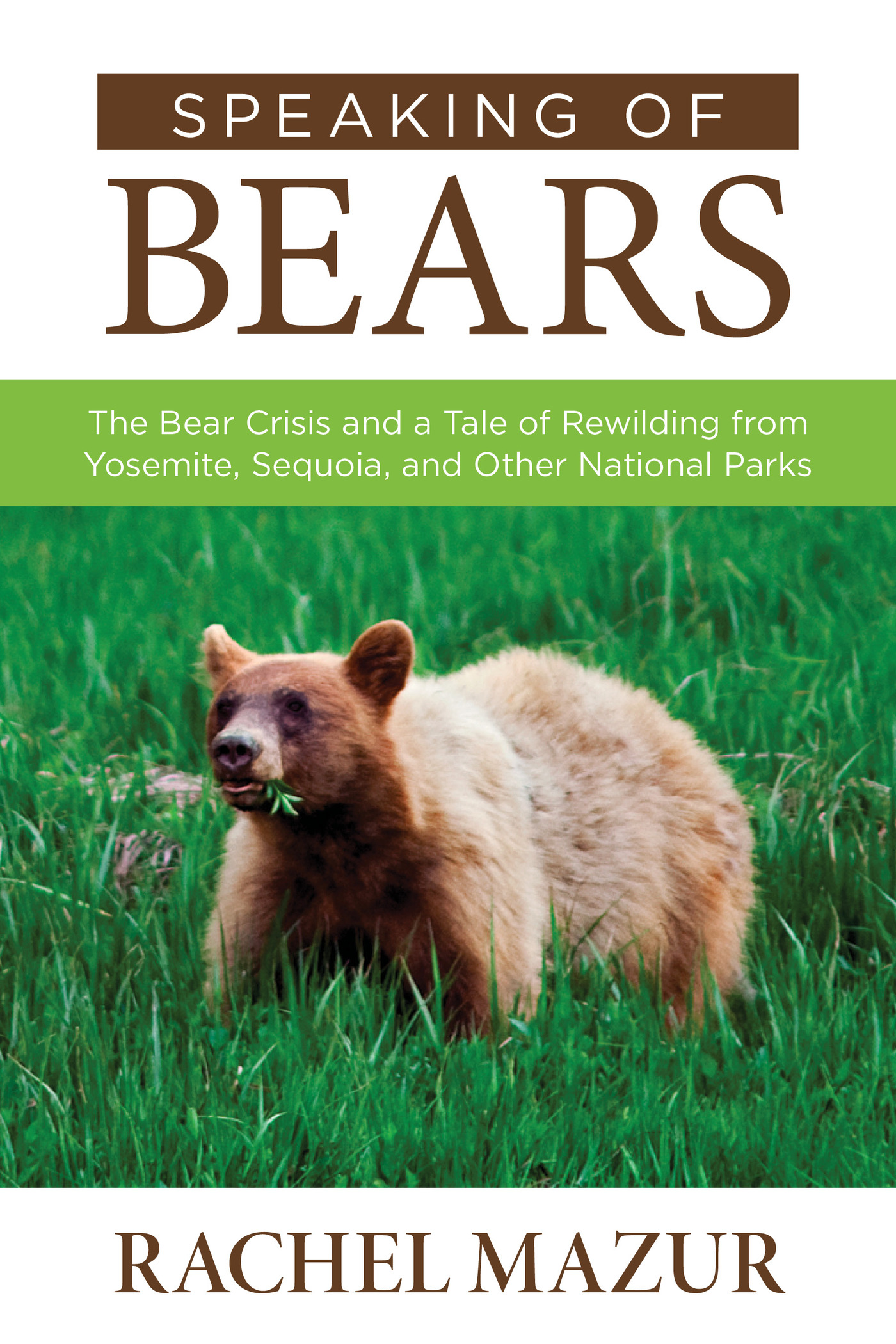

Speaking of Bears

Praise for Speaking of Bears

Speaking of Bears is a fascinating, rare, and eminently readable behind the scenes look at the complex world of bear management. It is filled with the stories behind the stories, all told by the people who lived them. After reading this book, even the casual bear aficionado will understand why it often takes more than sound science to solve human-wildlife conflicy; it also takes curiosity, intelligence, perserverance, and passion.

Linda Masterson, author, Living With Bears Handbook,

updated 2nd edition

Speaking of Bears is not only an essential history of bears in the Sierra, but an invaluable roadmap on how to balance wildlife and parks in the years to come.

Phil Schiliro, Former Special Advisor and Director of Legislative Affairs to President Barack Obama

Rachel Mazur has made a substantial contribution to the behavioral science research with this insightful work, but perhaps more importantly, she brings these stories to life.

Sean OKeefe, Fellow of the National Academy of Public Administration, Former Administrator of NASA, Secretary of the Navy, and Deputy Assistant to President George H. W. Bush

Until recently, black bears wanting peoples food or edible garbage in Yosemite, Sequoia, and Kings Canyon National Parks broke into cars, ripped into tents, threatened people, and more. Mazur tells the story of how the parks finally became close to bear proof by building her book around quotes from the people who were on the front lines of bear management. What results is a lively, fascinating tale.

Stephen Herrero, PhD, professor emeritus at the University of Calgary and author of Bear Attacks: Their Causes and Avoidance

Speaking of Bears

The Bear Crisis and a Tale of Rewilding from Yosemite,

Sequoia, and Other National Parks

Rachel Mazur

Guilford, Connecticut

Helena, Montana

An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Falcon, FalconGuides, and Outfit Your Mind are registered trademarks of

Rowman & Littlefield.

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2015 by Rachel Mazur

Maps by Melissa Baker Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-1-4930-0822-3 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-4930-1498-9 (e-book)

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The author and Rowman & Littlefield assume no liability for accidents happening to, or injuries sustained by, readers who engage in the activities described in this book.

For my father, who inspires me with his curiosity.

Preface

It was well after seven o'clock on a summer night in 2001 when Harold Werner, a longtime wildlife ecologist at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, Michelle [Monroe], and I arrived on site, but we had our capture equipment ready. As soon as Harold got a clear view of the unsuspecting black bear through the ponderosa pine trees outside Lodgepole Campground, he loaded the Telazol-filled dart, took aim, and squeezed the trigger. Even from a long distance at dusk, Harold darted the bear, also known as K95, perfectly in the rump.

Michelle and I then had the job of following K95, not so closely that he would run, but near enough not to lose him. At the time, I worked for Harold as the parks wildlife biologist, and Michelle worked for me as the lead bear technician. So off we went, over downed trees and boulders, and straight into the river where the bear decided to sit down, rest his head, and go into a deep, drug-induced sleep. Harold caught up quickly and held the bears head out of the water with the barrel of his dart gun. Meanwhile, Michelle and I scrambled up the hill to the employee recreation hall for help and blankets. It was late, and the only people there were three slightly inebriated off-duty maintenance workers who agreeably stumbled after us to help. Together, we pulled the four hundred-pound bear out of the river, wrapped him in a silver space blanket covered with a wool blanket for extra warmth, and put Michelle on top to keep him from slipping into hypothermia.

Evening became night before the drug wore off enough for K95 to stand and shake off the wool blanket. He wobbled, turned, and walked directly back to the campground, only now with new ear tags, a radio collar, and the silver blanket stuck to him like a superheros cape as he moved out of sight. Sadly, there were no real heroes in this particular tale because K95 had to be destroyed on his next capture. His habits of bluff charging employees and breaking into latched dumpsters would no longer be tolerated when they escalated into bluff-charging visitors and breaking into occupied trailers.

That was the tail end of a decades-long period when nights like this were business-as-usual for those living in the Sierra Nevada. Being immersed in that constant drama with bears, on top of being in charge of making it betterat least in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National ParksI often wondered how the situation became so bad and what had been tried over the years to fix it. Although a small part of that history can be found in annual reports, research summaries, and published articles, the bulk of it has never been documented. I therefore sought to learn the history by asking some of the longer-term employees, but found no one knew much beyond their own experience. Frustrated by the lack of information about the past, I went back to working with my mind solidly in the present. Then in 2009, I left my park job and moved to Reno to work for the U.S. Forest Service. During a family vacation to New York, I visited Ellis Island and and saw how to use oral histories to collectively research the past. Armed with new energy and the hope the people I sought were still alive and accessible, I started to interview them and record their memories. At the end of each interview, the interviewee would direct me to others who were involved with bears, and I found that while each person knew a different piece of the history, collectively, they knew the whole story.

Pat Quinn, a former trail crew member, recalled successfully reviving a bear with CPR after it was accidentally overdosed with Sucostrin. Dave Graber, the recently retired chief scientist for the Pacific West Region of the NPS and former bear researcher, described the trials and tribulations of installing the first food-storage lockers in Yosemite. Long-term wilderness ranger George Durkee explained how he and Mead Hargis figured out how to counterbalance rather than tie-off a backcountry food hang. Barrie Gilbert, an expert in bear behavior who was once badly mauled while studying grizzlies, explained the unexpected way he first conceived the idea to build a bear-resistant food canister. Former Yosemite biologist Kate McCurdy recalled making daily morning rounds to release bears stuck in dumpsters until her neighbor had an aha moment and thought of the simple solution that finally bear-proofed the dumpsters. As I listened to these people talk about past mistakes, failures, and successes, I realized how much could be learned from their stories, and

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.