Acknowledgments

For many years, all of my English publications have been edited by my wife, Alice Ogura Sato, and I take this opportunity to express my deepest appreciation for her dedication.

My great appreciation goes to Ms. Beth Corwin and Mr. Tom Wolsky, who readjusted their very busy schedules to help create the DVD. I am also grateful to Mrs. Betzi Robinson, past president of the Sumi-e Society of America, and to Mrs. Joan Lok, the current president of the Sumi-e Society of America, who both have provided information for this book; and to the members of Tuttle Publishing, especially senior editor Sandra Korinchak, editorial supervisor June Chong, and senior graphic designer Chan Sow Yun.

Finally, I would like to dedicate this book to the students who attended my intensive sumi-e workshops and eventually became my friends, who inspired me to take my creative energy to new heights in the constant search for a fresh way to create the art of black ink.

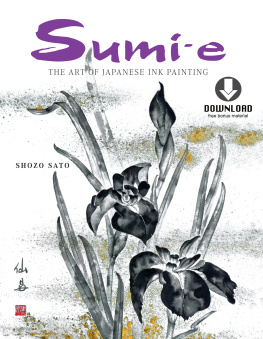

CHAPTER 1

The Art of Black Ink

The Relationship between Calligraphy and Painting

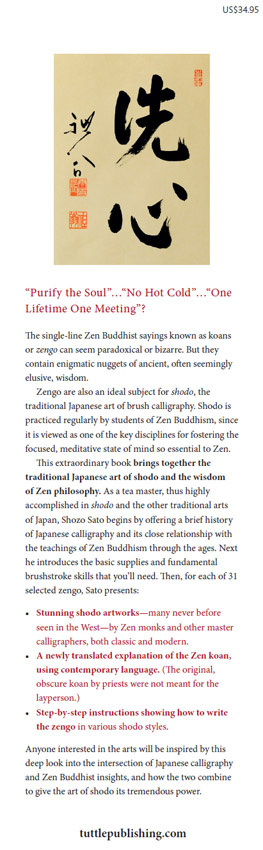

Among the historical differences between European-based cultures and the Far East is the method and tools of writing, so important for communication and keeping records. From the earliest times, a brush was used for writing in China and this practice continues today in many areas of Asia. The use of the brush as a tool in both writing and painting makes it difficult to draw a clear demarcation between them; there is an overlap between the utilitarian and the fine arts.

As we learned earlier, during the periods in history when China was ruled by emperors, among the populace were very well educated landlords and priests who were accustomed to dealing with brush, ink and paper every day. During their daily activities of copying sutras or writing documents for the government, they would take a break from their work to enjoy composing poetry and often would add a simple paintings to their work. Whether one would call it writing or painting, these works by the literati gradually became recognized as a genre of art. In Japanese their work is called bunjin-ga ( bun = letter, jin = person, ga = painting).

It has been recorded that the earliest Chinese paper appeared around 206 B.C. during the Han Dynasty. It is generally supposed that the fibers from various plants woven for clothing, such as varieties of flax, were also used for making of paper. Archaeological finds in remote Chinese provinces include paper made from flax. Eventually fibers from other plants began to be used. As papermaking developed from the primitive to the sophisticated, the making of sumi ink from soot was also perfected. As the availability of paper became widespread and brushes of various types and sizes were developed, both writing and painting undoubtedly became more commonplace. In the Far Eastern countries down through the ages, all documents and other written forms of communication required sumi ink and brush, until European cultural influences brought new ways to write. Today, the world over, the convenience of ballpoint pens, fountain pens and pencils makes them a daily necessity. And computer-generated text e-mails and such has taken over much writing.

Yet, writing with a brush continues today. In contemporary Japan, every first grader in school learns to write with a brush in a special class reserved for calligraphy. In contrast to pens and pencils, the use of a brush, whether for calligraphy or painting, carries with it established methods and rules both historically and traditionally developed. The various types of brushes and the effect they leave on the various kinds of paper are of paramount importance. The amount of ink the brush can hold must be controlled and the effects created when painting lines, from wide to narrow, in tones from dark to light, requires knowledge, skill and experience. When one is taught as a child, this may become routine, but when an adult is confronted with brush, ink and paper for the first time, it can be a daunting challenge.

Learning some basic lessons from writing can help you. The brush is used in a similar way for both calligraphy and painting, and I feel that learning the use of brush through calligraphy brings better understanding of the basic qualities of lines for a painting. Therefore, I consider this a very important first step.

When writing with a ballpoint pen, one moves the tip continuously across the paper, but when writing with a brush, one often lifts it up and then down as it moves across the paper in order to create a line which narrows or widens. When writing with a brush, the movement will be a combination of right to left and up and down. This simple movement appears to be easy, yet it is difficult to master. Here are some helpful ways to learn and embody the key principles and to make a physical connection with sumi-e.

KNOWING THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A PEN AND A BRUSH: ENERGY

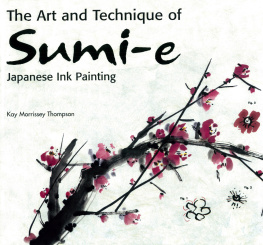

To understand the difference between the use of a brush and a ballpoint pen, let us first turn to the ideogram dai (great, big).

Use your pointing finger as an imaginative brush, and trace the character on the next page. Beginning on the left end of the horizontal line, give your finger a little pressure, then relax the pressure and move on to the right.

When you come to the end of the stroke, repeat a similar pressure but in addition bring your fingertip back a bit on the line, then lift your finger up. (This horizontal line alone is the ideogram for the number one. You have already written a word!)

The next stroke to trace begins at the top and moves to the left bottom. Give a slight pressure at the beginning and move down with a slight curvature, then gently release your finger from the paper. Your fingernail should be last to leave the paper.

The next stroke begins near the joint of the horizontal and upright lines. Make contact with the paper with your fingernail first, then as you move your finger to right bottom, the ball of the finger should make contact with the paper and give pressure. Gradually release the pressure so that your fingernail is the last to leave the paper.

Now you have experienced the writing of the ideogram of great. This simple exercise shows how different the use of a brush is from a ballpoint pen or pencil. Energy is a key difference. In the instructive text here, pressure with the fingers is used as a convenient way to explain the process but in reality, these pressures should be internalized chi or ki , energy which is centered in the lower abdomen to form a unity of body and spirit. The pressure of the ball of your finger should be accompanied with your inner energy. In the yin-yang balance of energy, this energy is considered yang. When pressure is reduced while the finger is moving to the right in the first stroke of dai the energy becomes yin, but the increased ending pressure is again yang. We can say, with only slight exaggeration, that the energy balance among yang-yin-yang has been experienced in this one line. This is the uniqueness of the use of black ink with a brush.

This ideogram is dai , or great. Following the exercise steps in the text, trace over it with your index finger to better understand the intrinsic nature of brushwork.