PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 2019

Text copyright Emma Smith, 2019

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Book design by Matthew Young

Cover by Matthew Young

ISBN: 978-0-241-36164-1

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

For Elizabeth Macfarlane

Introduction

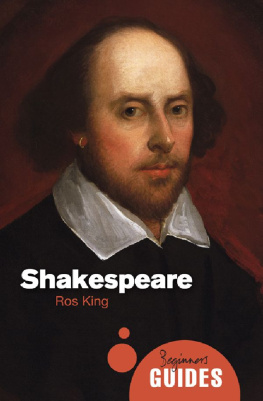

Why should you read a book about Shakespeare?

Because he is a literary genius and prophet whose works speak to more, they encapsulate the human condition. Because he presents timeless values of tolerance and humanity. Because his writing is technically brilliant and endlessly verbally inventive. Because he put it all so much better than anyone else.

Nope.

Thats not why; not at all. Sure, thats what we always say about Shakespeare, but it doesnt really get to the truth about the value of these works for the twenty-first century. The Shakespeare in this book is more questioning and ambiguous, more specific to the historical circumstances of his own time, more unexpectedly relevant to ours. Lots of what we trot out about Shakespeare and iambic pentameter and the divine right of kings and Merrie England and his enormous vocabulary blah blah blah is just not true, and just not important. They are the critical equivalent of dead-catting in a meeting or negotiation (placing a dead cat on the table to divert attention from more tricky or substantive issues). They deflect us from investigating the artistic and ideological implications of Shakespeares silences, inconsistencies and, above all, the sheer and permissive gappiness of his drama.

That gappy quality is so crucial to my approach that I want to outline it here. Shakespeares plays are incomplete, woven of whats said and whats unsaid, with holes in between. This is true at the most mundane level: what do Hamlet, or Viola, or Brutus look like? A novelist would probably tell us; Shakespeare the dramatist does not. That means that the clues to personality that we might expect from a novel, or from a film, are not there. If The Taming of the Shrews Katherine looks vulnerable, or ballsy, or beautiful, that makes a difference to our interpretation of this most ambiguous of plays, and if her imposed husband Petruchio is attractive, or boorish, or nervous, that too has an impact. Fantasy casting where you imagine a particular modern actor in a role is a very interesting game to play with Shakespeares plays: if you cast action-guy Mel Gibson as Hamlet (as Franco Zeffirelli did in 1990), you immediately produce a particular take on the play, which is quite different from casting Michelle Terry (at Shakespeares Globe in London in 2018), or Benedict Cumberbatch (directed by Lyndsey Turner, 2015). That we dont know what characters look like is one symptom of the absence of larger narration and commentary in a play. No authorial or narrative voice tells us more than the speeches of the characters themselves. Stage directions are relatively sparse and almost never tell us how a given action was performed: does Richard II give over his crown, orb and sceptre in Act 4 of his play to Bolingbroke sadly, gleefully, manically, or in fact not at all? The plays choreography is not spelled out for us, leaving this scene typically open to directorial and readerly imaginations. Shakespeares construction of his plays tends to imply rather than state; he often shows, rather than tells; most characters and encounters are susceptible to multiple interpretations. Its because we have to fill in the gaps that Shakespeare is so vital.

And there are larger conceptual and ethical gaps too: the intellectual climate of the late sixteenth century made some things newly thinkable (that religion is but a childish toy, as Shakespeares contemporary Christopher Marlowe had one of his characters claim), and overlaid old certainties with new doubts. Shakespeare lived and wrote in a world that was on the move, and in which new technologies transformed perceptions of that world. The microscope, for example, made a new tiny world visible, as Robert Hooke uncovered in his book Micrographia (1665), illustrated with hugely detailed pictures including fleas as big as cats. The telescope, in the work of Galileo and other astronomers, brought the in-effably distant into the span of human comprehension, and theatre tried to process the cultural implications of these changes. Sometimes, Shakespeares plays register the gap between older visions of a world run by divine fiat, and more contemporary ideas about the centrality of human agency to causality, or they propose adjacent worldviews that are fundamentally incompatible. These gaps are conceptual or ethical, and they open up space to think differently about the world and experience it from another point of view.

Gappiness is Shakespeares dominant and defining characteristic. And ambiguity is the oxygen of these works, making them alive in unpredictable and changing ways. Its we, and our varied engagement, that makes Shakespeare: its not for nothing that the first collected edition of his plays in the seventeenth century addressed itself to the great variety of readers.

His works hold our attention because they are fundamentally incomplete and unstable: they need us, in all our idiosyncratic diversity and with the perspective of our post-Shakespearean world, to make sense. Shakespeare is here less an inert noun than an active verb: to Shakespeare might be defined as the activity of posing questions, unsettling certainties, challenging orthodoxies, opening out endings. I wanted to write a book about Shakespeare for grown-ups who dont want textbook or schoolroom platitudes. Not a biography (theres nothing more to say about the facts of Shakespeares own life, and vitality is a property of the works, not their long-dead author); not an exam crib (Shakespeares works ask, rather than answer, questions, making them wonderfully unsuited to the exam system); not a Shakespeare-made-simple (Shakespeare is complex, like living, not technically and crackably difficult, like crosswords or changing the time on the cooker): I wanted to write something for readers, theatregoers, students and all those who feel they missed out on Shakespeare at some earlier point and are willing to have another pop at these extraordinary works.

We all know Shakespeare occupies a paradoxical place in contemporary culture. On the one hand his work is revered: quoted, performed, graded, subsidized, parodied. Shakespeare! On the other hand cue yawns and eye rolls, or fear of personal intellectual failure Shakespeare can be an obligation, a set text, inducing a terrible and particular weariness that can strike us sitting in the theatre at around 9.30 p.m., when we are becalmed in Act 4 and theres still an hour to go (admit it weve all been there). Shakespeare is a cultural gatekeeper, politely honoured rather than robustly challenged. Does anyone actually like reading this stuff?

Next page