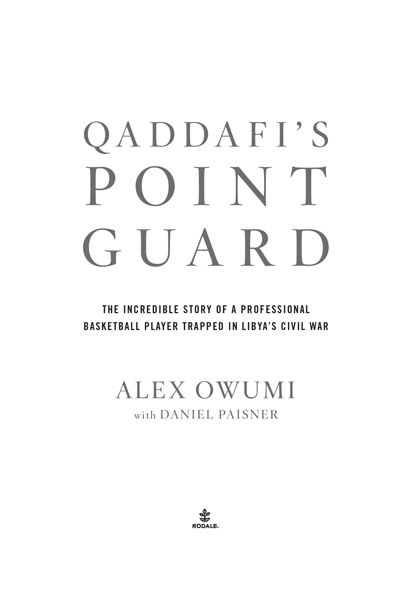

To God, to my family, and to all the lives that were lost during the Arab Spring

Although your people live in darkness, they will see a bright light.

Although they live in the shadow of death, a light will shine on them.

MATTHEW 4:16

CONTENTS

FEBRUARY 17, 20118:42 A.M . EET

Just up from a late practice the night before. Had my driver, Osama, stop for some pizza on the way home. He knows just a few words of English. He knows my name, Alex. He knows come and practice and bank and market. He knows the pizza place I like, where they make it fresh. He pretty much has all my basic needs covered.

Hes a funny guy, a good guy. Always talking shit about Qaddafi. I cant understand a word he says, but I can tell hes talking shit. Its like hes spitting the word Qaddafi onto the dashboard in front of him, like it disgusts him to even have the mans name on his lips. Osamas like a lot of the Libyans Ive met in the short time Ive been herevery expressive. We dont speak the same language, but their body language gives them away. When they are happy, I can tell. When they are angry, I can tell. When they are confused or overwhelmed, I can tell this, too, and with Osama I can tell this most of all. His mood is in his smile, in the way he spits Qaddafis name from his lips.

Id fallen asleep watching a European basketball game, and the television is still on when I wake up. Its a good thing I set the alarm. Without it, Id be dead asleep. With it, Im just dead tired. The plan is to hit the gym early, eight forty-five, just me and my coach. I want to stretch, get some shots in, work on a couple of things. Weve got a big game this weekend against our rival, Al-Ahly Benghazi. Its like the Celtics and the Lakers when our teams play, only with rocks and soda bottles being thrown onto the court. Last time we played was my first game for Al-Nasr, in a nice arena in Tripoli. Both teams are from Benghazi, but theres so much noise and excitement around these games that they need to put us in a big venue. The fans get into it, and so do the players, even if its just to avoid the rocks and the soda bottles, even if its a neutral-site game. Either way, itll be bloody, brutal. I want to be ready. I have not come all this way to play professional basketball in Libya, then sleep through my alarm just because Im dead tired.

Osamas running late. Hes not answering his phone, so I call my coach, Sherif Azmy. Coach Sherif is a local legend, the John Wooden of the Middle East. Hes got this reputation for running his players like crazy. Hes originally from Egypt, used to play himself. Knows his stuff: fundamentals, Xs and Os, all of that. Learned the game in the States, going around to Five-Star camps and clinics. Guys who play for him say he runs them so hard, it takes a couple of years off their careers, but he knows the game. He plays to win. Treats his players like family. Some, anyway.

Coach Sherif answers his phone like its already in his hand. He must recognize my number, because he answers in English. He says, What? (His English is good, but he doesnt want to wear it out.)

I say, Coach, its Alex. Im still waiting for Osama. Ill be a few minutes late.

He says, No, no, no. What are you talking about? Like Im crazy for even calling. Like Ive got no idea whats going on.

I say, For practice.

He says, There is no practice, Alex. Dont you see outside?

I cross to the window to see what he means. My apartment is on the seventh floor, overlooking the main square, the heart of Benghazi. The apartment actually belongs to one of Qaddafis sons, Mutassim, a lieutenant colonel in the Libyan army. Hes cleared out to make room for me for the run of the basketball season. Its furnished with his fine thingsbeautiful couches with gold trim, a big-screen television, interesting art. Hes about ten years older than me, but his tastes seem to come from another time. Still, its an amazing place. And convenient: two blocks from the arena where we play our home games; two blocks from the Al-Nasr Sporting Club, where we practice and train; one block from a place that reminds me of a Ruby Tuesday, where I take a lot of my meals.

I look out the window at a crowd of protestors on the street below. My view is obstructed by the other buildings, but it appears to be the same crowd from the day before, from the day before that. The same size, the same temper. Mostly men, some military. For four or five days now, there has been unrest. Shots have been fired into the air like exclamation points.

Since December, there has been a wave of protests throughout the Arab world. Demonstrations. Rallies. There has been the sudden overthrow of governments in Tunisia and Egypt. Last week, on what the newspapers are calling the Friday of Departure, Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak announced his resignation, following weeks of mostly civil disobedience. The news set off wild celebrations in the streets of Cairo and across the Middle East. I know this mostly because the pictures from these protests pop up on my home screen every time I go online. I do not know this from looking outside my window, from talking to people. I am too focused on basketball, on my team, to think too long, too hard about anything else.

Even so, the spirit of this Arab uprising is in the air and all around. It is impossible to miss. Here in Benghazi it has been a peaceable movement. That is how it starts: There is a call for change. There is anger and tension, yes, but there is also order and civility... for now.

Whatever is happening on the street below, it comes to me through my window like a lot of noise. It is nothing. And yet across the world, through the Internet, news of the protests on the streets of Libya reaches my family in the States like a warning. Just yesterday, before practice, my oldest brother Joseph pleaded with me on Skype to pack my bags and come home. He said, You have got to get out of there, Alex. Its bad.

I said, Its nothing. Everythings fine. Youll see.

Today, now, it still feels like nothingjust shouting and chanting and meaningless gunfire. I say as much to Coach Sherif. I say, This has been going on for four days, I say. This is nothing new.

He says, No, Alex, its turned. Theyre killing people. Look.

I look and look, but I cannot get a full view through my window, so I tell Coach Sherif Ill call him back. I set the phone down on the kitchen counter, then I open the heavy door to my apartment and take the steps to the roof two at a time. I live on the top floor, so it is only one flight. I have been to the roof almost every day since I arrived in Libya at the end of December. Its where I hang my clothes to dry when I do my wash. Its where I come to unwind, to take in the panorama of my strange new surroundings. From the roof, I can see the main square in front of my building. I can see across to the arena and over to the soccer field where I sometimes do my running. Today I look down and see the full swarm of protestors belowabout three hundred people, some of them wearing the deep green of the Libyan flag, pressed up against each other like they are at a concert. They are jumping, shouting, dancing. Almost everyone has a fist in the air in a show of defiance. There seems to be a great too many of them squeezed into a not-so-great, too-tight space.

The protesters all appear to be facing the same direction, looking at the same thing. I follow their gazes to a row of military police wearing white hats with a Libyan-green stripe. They are thirty, forty strong. They move slowly across the square to fill the space between the police line and the swarm of protesters. My first thought is that the police are only trying to break up the crowd, which has been bottlenecked into this narrow, open space.