Discovering Chess Openings

John Emms

First published in 2006 by Gloucester Publishers Limited, London.

Copyright 2006 John Emms

The right of John Emms to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic,

electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without prior permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 78194 582 7

Distributed in North America by National Book Network,

15200 NBN Way, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 17214. Ph: 717.794.3800.

Distributed in Europe by Central Books Ltd.,

Central Books Ltd, 50 Freshwater Road, Chadwell Heath, London, RM8 1RX.

All other sales enquiries should be directed to Everyman Chess.

email: info@everymanchess.com; website: www.everymanchess.com

Everyman is the registered trade mark of Random House Inc. and is used in this work under licence from Random House Inc.

Everyman Chess Series

Commissioning editor and advisor: Byron Jacobs

Typeset and edited by First Rank Publishing, Brighton.

Cover design by Horatio Monteverde.

Symbols

+ check

!! brilliant move

! good move

!? interesting move

?! dubious move

? bad move

?? blunder

1-0 The game ends in a win for White

0-1 The game ends in a win for Black

- The game ends in a draw

Introduction

The study of chess openings is difficult and never-ending. Its like Pandoras box: the more you study, the more there is to learn; and the more you learn, the more you realize how little you know. If thats the opinion of someone whos been trying for nearly 30 years to get to grips with openings, how does a newcomer to chess find this ever-spiralling science? Intimidating, or is that too mild a description?

So what is an aspiring player supposed to do? Although not strictly relevant here, I cant help but be reminded of one of Bobby Fischers famous quotes. On being quizzed over chess lessons, Bobby Fischer advised his biographer and founding editor of Chess Life magazine, Frank Brady, (tongue-in-cheek, Im sure): For the first lesson, I want you to play over every column of Modern Chess Openings, including the footnotes. And for the next lesson, I want you to do it again. Of course it goes without saying that opening encyclopaedias are an important part of chess literature, but I do wonder how I would have found the experience as a junior player of ploughing through the latest volume of intense opening theory. A bit bewildering, perhaps?

This book is a bit different and is mainly aimed at those who know nothing or very little about chess openings. Its also for those who do know some moves of opening theory, who have happily played these moves in their own games, but are perhaps not quite sure why they play them! One of my main aims was to give the reader enough confidence to face the unknown; to be able to play good, logical moves in the opening despite in many cases having a lack of concrete knowledge of the theory. After all, even in grandmaster games there comes a point when one or both players runs out of theory and has to rely on general opening principles, and sometimes this is sooner than you would think.

The initial inspiration behind Discovering Chess Openings stemmed from coaching sessions I did with some young students not experienced enough to have any real knowledge of opening theory. After revising the basic principles of opening play, I decided as exercises to give them a number of positions from typical openings, often only three or four moves deep into the game. I then let them spend some time finding logical moves and, in turn, appropriate replies to these moves. The idea was to find out how players with little or no knowledge of opening theory but with some understanding of general opening principles would fare when confronted with an opening position they knew nothing about.

This concept really appealed to me. The traditional approach had been to carefully go through the mainline openings, taking measures to explain the reasoning behind each move, but somehow it seemed so much more beneficial (not to mention more fun!) to watch the students trying to work out the best moves of their own accord; basically, trying to recreate opening theory! It was fascinating to revisit well known positions with players whose views were not influenced by previous knowledge; this definitely brought a certain freshness to their ideas. On the other hand, some suggestions that were made did reinforce one or two common misconceptions amongst improving players, and Ive included these in the book to emphasize what we should be particularly looking out for.

This book has also given me the opportunity to expand on a number of topics which arose when I was writing Concise Chess, a general guide for absolute beginners. These themes were too advanced for that book, so I was happy to be able to include them in a more suitable place.

Finally, a brief paragraph about how the book was written and what it contains. The first three chapters introduce the three main ideas behind opening play:

1) Control of the centre

2) Rapid piece development

3) King safety.

There are other important concepts, but as far as I can see these are usually just subsets of these three. Chapters 4 and 5 delve more deeply into these themes, with the latter chapter concentrating on the role pawns play in the opening. Finally, in Chapter 6 we take all the ideas of the previous chapters and see how they are used to create modern opening theory.

Whilst many mainline openings can be found within these pages, not everything under the sun is covered. As Ive already mentioned, it was never the intention to be encyclopaedic. Perhaps Ive indulged a little more in 1 e4 e5 openings, and if so I make no excuses for this. In my experience, these are the first openings that many newcomers learn, so they are likely to come across these more frequently than other openings in the initial stages of their development.

I think Ive said enough. I hope you enjoy this book and wish you the best of luck discovering chess openings!

John Emms,

Kent, July 2006

Chapter One

Central Issues

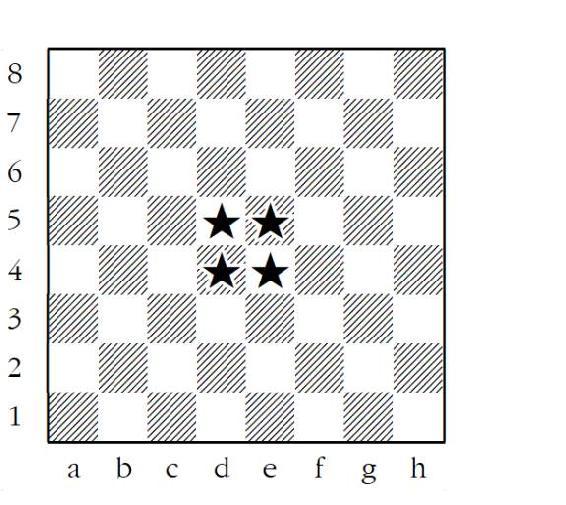

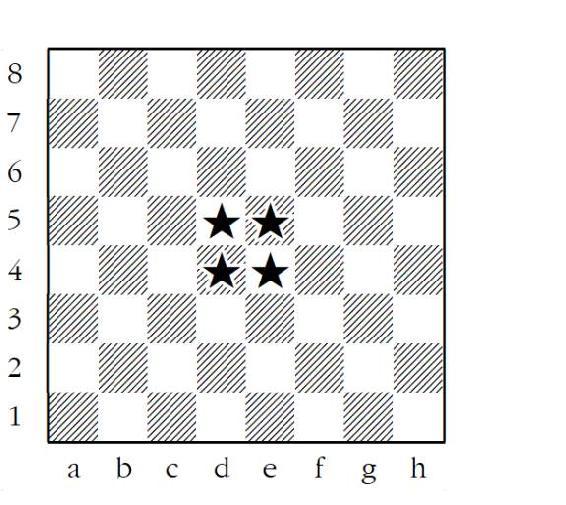

What is the centre? Okay, I admit this sounds a silly question, but even so Id be happier if I were able to confirm one or two definitions here. The centre is very often considered to be simply the four squares highlighted in the diagram below: e4, d4, e5 and d5.

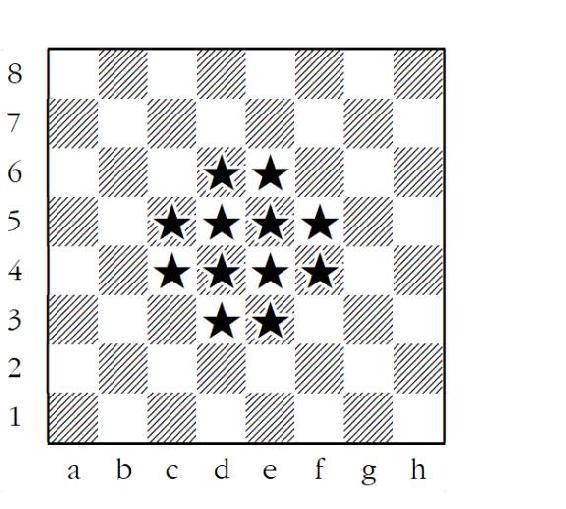

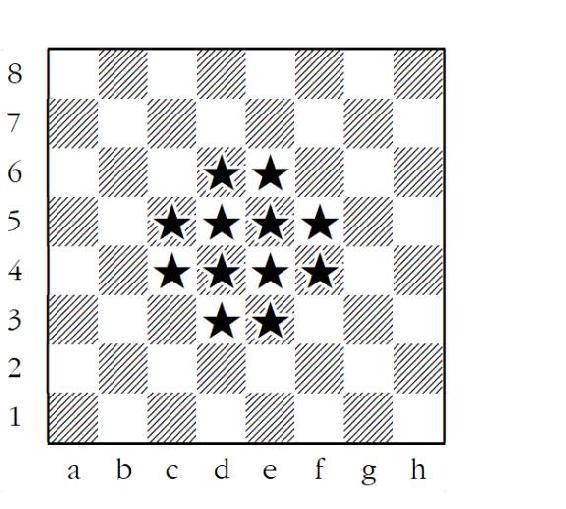

This definition, however, has always seemed a bit restrictive to me. I think you lose something if you say these four squares are the centre, everything else isnt; I dont think its as black and white as that (excuse the pun!). For this books purposes Id like to expand the centre a little to include the squares c4, c5, f4, f5, d3, e3, d6 and e6 (see the following diagram).

Id be the first to admit that these extra eight squares arent quite as important as e4, d4, e5 and d5, but they still carry some significance and so I think its right to include them here.

Why is it important to pay attention to the centre? Why not ignore the centre and play only on the flanks?