NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2019 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

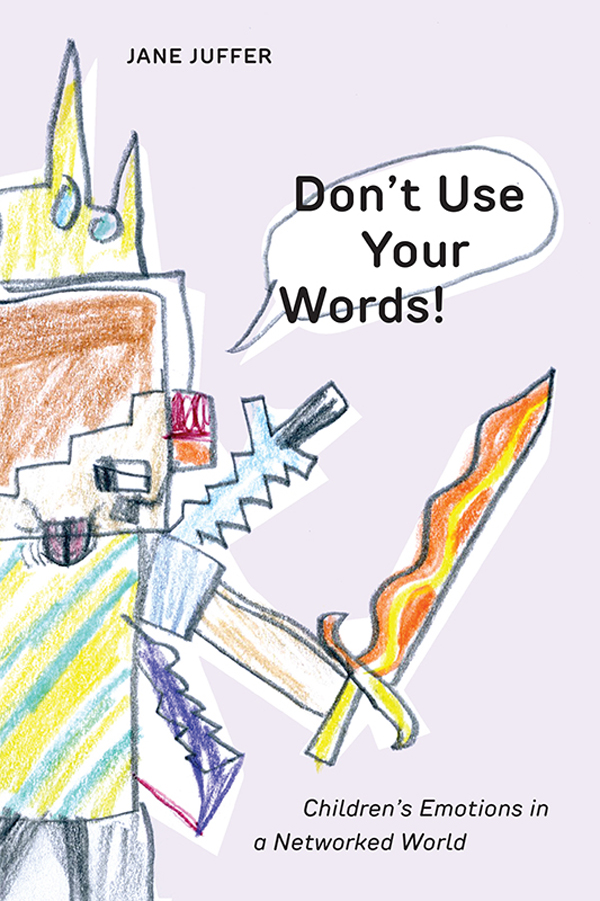

Names: Juffer, Jane, author.

Title: Dont use your words! : childrens emotions in a networked world / Jane Juffer.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018037668| ISBN 9781479831746 (cl : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781479833054 (pb : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Emotions in children. | Television and children. | Mass media and children.

Classification: LCC BF 723. E 6 J 84 2019 | DDC 155.4/124dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018037668

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

Introduction

Run Over by a Unicorn

What if you could see your feelings, and they were chasing you? says the child. Which one would be fastest? I ask. Quickness, he responds. But is that a feeling? I ask. Of course. I feel quick this morning. Sometimes I feel slow. And another morning, upon waking, he comments, I feel like Ive been run over by a unicorn.

Ezra, six years old

The scene in the therapists office goes something like this: she points to the chart on the wall with its rows of faces typifying different expressionshappy, sad, hopeful, angry, frustrated, scared; there are almost 50 faces represented. Then she asks the seven-year-old to point to which face best describes how he is feeling. The idea, she explains to the parent, is if children can put a label on it, they can begin to manage their emotions. Children often respond bodily when they are feeling out of control, she adds: they may hit or scream or run away. If they can name the feeling, they may be able to respond with their words rather than their bodies. The child, however, is not convinced. He studies the chart for a few minutes, then responds, How Im feeling is not there. She asks what he is feeling. Irritated, he says, sighing. Can I go now?

The gap in expression between adult and child is at the heart of this book. My goal is not to close the gap but to let it remain, to perhaps even widen it, in the interest of allowing children a semi-autonomous space in which to express themselves. I do not dispute the importance of therapy for some children, nor the need for a language children can use to help them navigate the world. I am convinced, however, that this language, often taught by the most well-intended adults, fails to capture childrens affective intensities even as it valorizes the realm of emotional expression. In fact, the very objective of naming ones emotions in the interest of controlling ones body almost certainly dampens the intensity and range of the feelings and their expression, especially their expression through the body. Self-regulation becomes appropriate bodily comportment. Extreme emotions should be subsumed, with happiness and niceness the goal. In the language of problem solving that has become central to television programming for young children, the problem that needs to be solved is the emotion that threatens social order. Being run over by a unicorn would not be considered a viable expression.

Media for children is one of the primary sites for the production of this therapeutic discourse. It is also one of the primary sites available to kids for creating alternatives to the management of emotions. This negotiation, this struggle, drives this book. On one side, the discourse of emotional intelligence across educational, therapeutic, and media sites aimed at young children valorizes the naming of certain emotions in the interest of containing affective expressions that dont conform to the normative notion of growing up. On the other side, kids, through the appropriation of these media texts and the production of their own culture, especially on the internet, resist these emotional categorizations, creating an archive of feelings Why do so many policy makers, parents, and pedagogues treat feelings as something to be managed and translated?

The therapeutic influence on media produced for kids is sometimes derived directly from the private-sector counseling world; there exists what Stuart Hall would call an articulation, bringing together the sites of childrens television, therapy, parenting, and elementary education. For example, three Nickelodeon preschool shows Ni Hao, Kai-Lan ; Blues Clues ; and Wonder Pets used the consulting services of a therapist named Laura G. Brown to advise them in creating the characters and the stories. Nickelodeons 2007 press release announcing the premiere for Ni Hao, Kai-Lan , a show featuring a five-year-old Chinese American girl, described Kai-Lan as an emotionally gifted child who is driven to understand the world and how things are linked together both physically and emotionally (quoted in Hayes 2008, 42). A recent article in Psychology Today is headlined Can TV Promote Kids Social-Emotional Skills? Help Your Child or Student Learn Positive Social-Emotional Lessons from TV (2014). Its authors, academics Claire Christensen and Kate Zinsser, draw on and quickly redirect the familiar concern that television causes kids to be violent: As a parent or educator, youve heard it before: violent TV creates violent children. But, what about TV shows that depict getting along with others, solving problems, or handling emotions constructively? If kids can learn to fight from the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, can they also learn to share from Daniel Striped Tiger? Their answer is yesif the shows feature characters with strong socioemotional skills such as sharing and if parents engage their children in conversation about what is being represented. They should ask questions such as Did you see Dora cooperate with Boots? Why did she do that? How did it make Boots feel? and You look nervous. Do you want to try taking deep breaths like Rabbit did?

The therapeutic approach puts a new spin on the title of Marie Winns influential 1977 The Plug-In Drug, in which she lamented televisions addictive effects on children and urged parents to regain control of the powerful medium. Television is still a drug, but now its a helpful drug, like the stimulants used to treat kids with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In fact, one executive in the childrens television industry, in response to the criticism that television can become addictive to children, said, Everything is fine as long as the dosage is right. Its prescription drugs being given without a prescription. If you take too much, you get a stomachache. If you take the right amount, your headache is gone (quoted in Hayes 2008, 15). Receiving the right dosage makes children more, not less, socially adjusted.