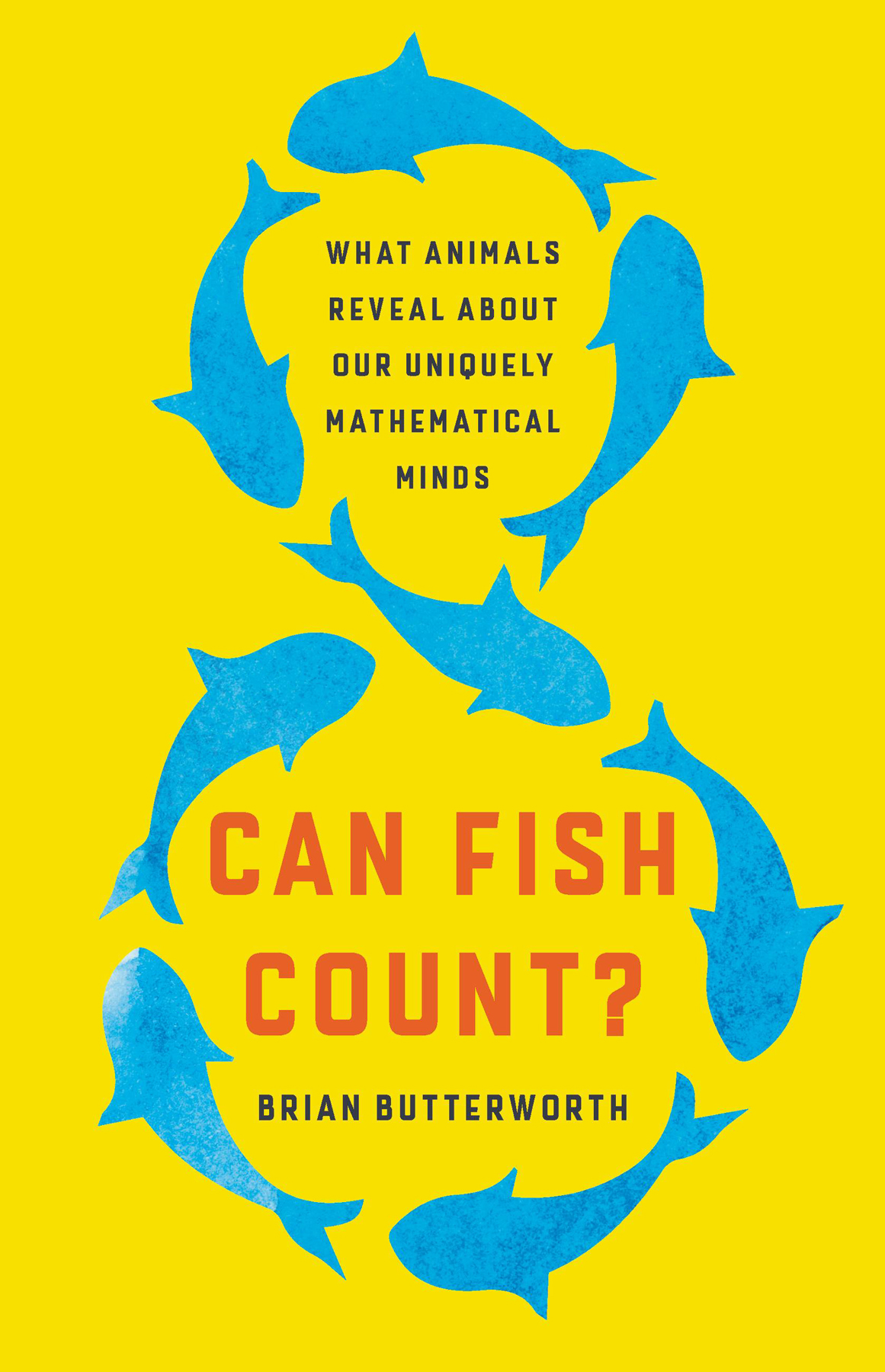

Copyright 2022 by Brian Butterworth

Cover design by Chin-Yee Lai

Cover images ami mataraj / Shutterstock.com; VETOCHKA / Shutterstock.com

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

Originally published in 2022 by Quercus in Great Britain

First US Edition: April 2022

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Illustrations by Jeff Edwards

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022931977

ISBNs: 9781541620810 (hardcover), 9781541620827 (ebook)

E3-20220318-JV-NF-ORI

To Diana, Amy and Anna, who all count

Modern science is a team sport. Whos in the team is partly a matter of luck, and I regard myself as being particularly lucky in the teams Ive played with over the years. Not only couldnt I have written this book without chance meetings over the years with many people, I wouldnt even have thought about it.

One such meeting, at a conference in Ravello, was with Carlo Semenza, psychologist, psychiatrist and neuroscientist from Padua University in Italy. This led to a long collaboration, initially on disorders of language, but latterly on mathematical cognition and their disorders.

I probably wouldnt have started thinking seriously about numerical abilities without the initial prompt of my then-student Lisa Cipolotti. Lisa was one of Carlos brilliant students, who asked to come to London to do a PhD on aphasia, but when she actually arrived she decided that rather than aphasia which was very well studied she wanted to work on a disorder very few people were researching. So we agreed to study the neuropsychology of mathematics, which at that time very few people anywhere were working on. Together with Carlo and his Austrian student Margarete Hittmair, we formed a team with the pioneering neuropsychologist Elizabeth Warrington at the National Hospital for Neurology in London, to investigate acquired disorders of mathematics, supported by a grant from the European Community. This also created a longer-term link between Padua and London that continues to this day.

Studying neurological patients revealed, first, that the key brain region for numerical processes was in a small part of the parietal lobe, and the adult brain network appeared to be independent of other cognitive processes (this was not a new discovery, but recapitulated in more detailed studies going back to the 1920s), but more interestingly it seemed to be organized into distinct components, each of which could, in some cases, be separately affected by brain damage. This was the adult brain, but I started to think that about how the brain develops these components and why these particular regions. Do we inherit a brain organized to extract numerical information in the environment? And if so, how deep into evolutionary history do these roots go? Can this inheritance go wrong, as in colour blindness?

In 1989, when Lisa first came to work with me, studies of numerical cognition were confined to separate silos with very high walls: neuropsychology of mathematical disorders, adult cognitive psychology, child development, animal studies, mathematical education, philosophy of mathematics and the beginnings of brain imaging. Practitioners in these silos rarely talked to each other, but I and a few others thought that the whole field would be advanced if they did. Then came another slice of luck. My friend Tim Shallice, at the International School of Advanced Studies in Trieste, found some money to fund a week-long workshop in Trieste in 1994, with which we were able for the first time to bring together many of the worlds top scientists, and some of the worlds top students, and give them the opportunity to talk to each other. As an almost immediate result, I managed to organize and find funding for a European network of six labs, Neuromath, and then a second network of eight labs, Numbra, to collaboratively pursue this interdisciplinary approach. Through the Trieste meeting and the networks, I have been able to meet, discuss and collaborate with an astounding number of inspiring scientists. Stanislas Dehaene was at the Trieste meeting and has been one of the most important shapers of this whole field, and his contribution has been fundamental to my own thinking. No high-class symposium would be complete without a philosopher, and we were lucky that my colleague at UCL , Marcus Giaquinto, was an outstanding philosopher of mathematics, and was able to keep us, me in particular, on the philosophically straight and narrow.

One student who was in Trieste at the time but wasnt officially at the Trieste meeting was Marco Zorzi. He spent some time in my lab doing ground-breaking work on using neural networks to model reading, and later to model basic arithmetic processes. Currently, Professor Zorzi in Padua runs one of the most innovative labs in the world for mathematical cognition.

Randy Gallistel and Rochel Gelman also were at the meeting, where we became friends, and I have since spent many happy hours in various parts of the world, often starting at breakfast, with Rochel and Randy, arguing about the nature of mathematical abilities in humans and other animals. Their approach to these issues, as you will see, has influenced me profoundly.

Randy, Giorgio Vallortigara, a brilliant animal experimenter at the University of Trento in Italy, and I organized a wonderful four-day meeting at the Royal Society in 2017 on The Origins of Numerical Abilities that attracted an amazing group of scientists approaching the subject from many different perspectives, from archaeology to insects. Four days devoted to number actually five, because the previous day Ophelia Deroy organized an international symposium on the philosophy of mathematics at the Institute of Philosophy in London. Five days on number: I was in heaven. In one sense, this book is an attempt to make the contents of these meetings available to the general reader.

Christian Agrillo from Padua, at the time a student, first got me interested in the numerical abilities of fish. I am currently collaborating with Caroline Brennan and Giorgio on a project about the genetics on numerical abilities of zebrafish. Tetsuro Matsuzawa, who I first met at a Neuromath network summer school, invited me to the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University to observe his inspiring work with chimpanzees.

Fundamental to my whole approach has been my work with Bob Reeve on the early development of numerical abilities in mainstream Australia and with indigenous groups there.