Copyright 2022 by Cornell University

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu.

First published 2022 by Cornell University Press

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rigord, approximately 1145approximately 1209, author. | Field, Larry F., translator. | Gaposchkin, M. Cecilia (Marianne Cecilia), 1970 editor. | Field, Sean L. (Sean Linscott), 1970 editor.

Title: The deeds of Philip Augustus : an English translation of Rigords Gesta Philippi Augusti / Rigord ; translated from the Latin by Larry F. Field ; edited by M. Cecilia Gaposchkin and Sean L. Field ; foreword by Paul R. Hyams.

Other titles: Gesta Philippi Augusti. English

Description: Ithaca, [New York] : Cornell University Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021052230 (print) | LCCN 2021052231 (ebook) | ISBN 9781501763144 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781501763151 (paperback) | ISBN 9781501763168 (epub) | ISBN 9781501763175 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Philip II, King of France, 11651223. | FranceHistoryPhilip II Augustus, 11801223.

Classification: LCC DC90 .R5413 2022 (print) | LCC DC90 (ebook) | DDC 944/.023092dc23/eng/20220105

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021052230

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021052231

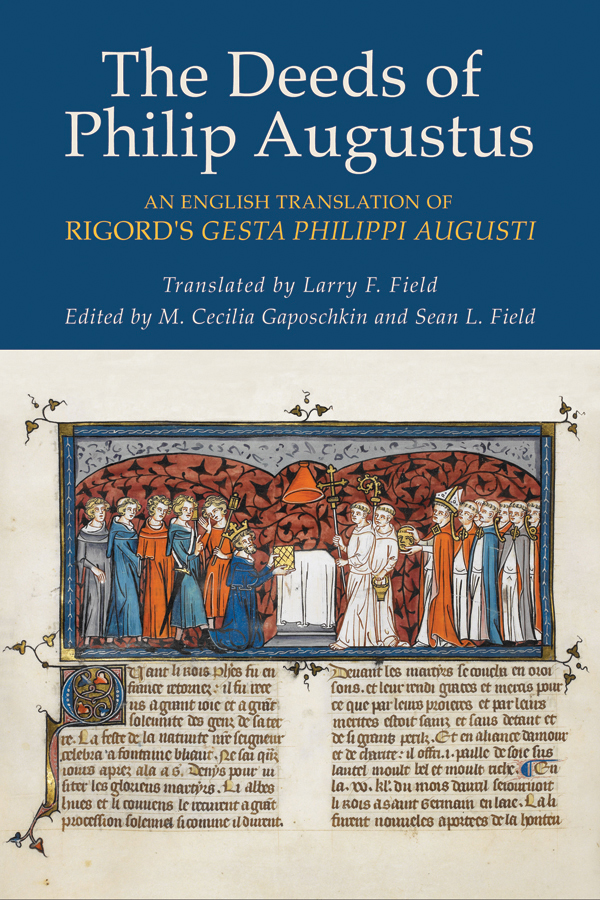

Cover art: Philip II making his offering to Saint-Denis. London, British Library, Royal MS 16 G VI, fol. 353v. Used by permission of the British Library.

Illustrations

Maps

Figures

Foreword

My acquaintance with Rigord is long-standing but began rather fortuitously. When I was still new at Cornell University, I started to create a course with two main aims. First, it would introduce students, who preferably had some knowledge of the Middle Ages already from my survey course, to the great watershed moment of the long twelfth century through an in-depth study of the French hexagon and the Capetian monarchy. Second, it would offer a variety of translated source texts, whole works where possible, to display the extra richness of primary materials over secondary studies.

This array of primary texts would illustrate key themes, including chivalry; the emergence of vernacular literature, especially French, and the transition from epic to romance with its new notions of love, continence, and binding marriage; and the myths about Arthur and the Grail. My students would have the opportunity to see what they could make of some masterpieces of medieval culture, not merely as beautiful works in themselves, but also as ways into the harsher realities arising with the systems of power within which everything operated. I looked especially for narrative texts on the twelfth-century resurgence of a nation-state in France. Sugers Life of Louis the Fat (d. 1137) was an obvious choice for the one bookend, as it were, but there was no evident equivalent on Philip Augustus (d. 1223) in English. I would have to provide something myself. Rigords life of Philip Augustus seemed an enticing proposition because of its unusual mixture of topics, among them the paving of Paris streets, the Third Crusade, Rigords obsession with the Jews, and his apparent fascination with eclipses. Additionally, I thought he offered a more than average number of passages to provoke fertile class discussion. What puzzles me is usually a good place to start such discussion.

One cannot rush a translation that must bridge the gulf between minds of the twenty-first century and the twelfth. My rough-and-ready translation only reached so far (the first ten years of Philip IIs reign) before the looming semester made me stop, for the time being. I hoped to return and complete the job, perhaps with a grad student partner who might use a first publication to impress the academic employment market. The first ten years was quite enough for a weeks reading anyway, and it quickly found its way beyond my campus via the Internet, where it remains to this day, my small contribution to the cooperative Internet I had always wanted to see. Though my effort was never completed, we now have something much better than I, no French historian, would have produced. This book is the real thing: a readable, accurate rendering of Rigords Latin presented in a form that one can certainly enjoy, but also use in the multifarious ways that a sound scholarly translation makes possible.

But possession of the book takes us only halfway. I have always felt that we scholars fail to remember from our own pasts how hard it is for readers new to the Middle Ages to make sense of its writings. The gulf between our minds and those of Rigord and his contemporaries remains massive. As someone once remarked, even if people could speak the language of lions, they would never experience a satisfying conversation with one. Still, a translation as carefully prepared as this one is a good place from which to prise our way into the France of Rigord and his king, especially if there is on hand a capable professorial guide to help. To get the best out of this text, students should actively look out for the passages that make no sense to them, grapple with these, and thenbut only thenchallenge their instructors to lead them on to a deeper understanding of what to make of the words. A generation before Rigord took up his pen, one great Parisian, Peter Abelard, encouraged his students to challenge him, telling them that by doubting they could be led to question, and through their questions hope to reach toward truth. So, ask on. If that is what a real-life professor in the first great university to emerge in northern Europe taught his students, we should hope for nothing less from ours, if they first give Rigord full enough attention to single out the most perplexing difficulties.

Let me end with one such passage that I only noticed late in my own reading, when I realized it presented questions I could not answer. The passage in question is found at the end of chapter 61 about the disastrous Third Crusade:

And note that in the very same year of our Lord when the Lords Cross in Outremer was captured by this same Saladin [1187], babies who were born since that time have only twenty-two teeth, or only twenty, when before then they would usually have thirty or thirty-two.

Any critical appraisal of this passage throws up all kinds of questions. What if anything could Rigords intended readership have made of it? Where did he get his information, and why did he bother? Did he really believe that God would change His global child development schedule to punish the crusaders in so esoteric a fashion for this specific default among so many? Why did Rigord even notice so minute a change? Numbers are otherwise scarce in his work. He shows no great interest in observation and causal explanations elsewhere. Where did he get these confidently precise ones?

A preliminary Internet search sheds some light, by confirming that whereas most adults do indeed possess thirty-two teeth, young children normally have no more than twenty milk teeth. Then, prompted by a friend, I searched for babies and twenty-two teeth. The results brought me to some later writers who peddled exactly the same numbers as Rigord, but used them to make sense of putatively punitive plagues without any mention of him or his cross. There must be a larger story here, one perhaps known to his few literate peers but not more widely. It seems unlikely that it began with Rigord. While it is not inconceivable that he had picked up his dental information orally, it more probably reached him from something he had read, possibly during his medical training. The next step is to pursue his words back into the early Middle Ages, which I can and will do in due course by usingthis being the twenty-first centurysearchable databases. Naturally being in Latin, these resources are open to me, but not to everybody.

Next page