ISBN 978-3-11-026595-8

e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-026640-5

e-ISBN (EPUB) 9783110370348

ISSN 2191-5806

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de .

2014 Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin/Boston

Typesetting: Drlemann Satz GmbH & Co. KG, Lemfrde

Printing and binding: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Gttingen

www.degruyter.com

Epub-production: Jouve, www.jouve.com

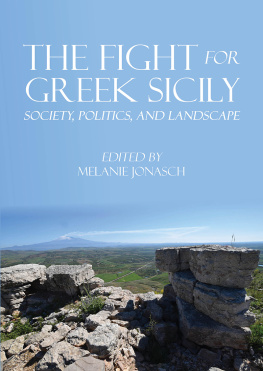

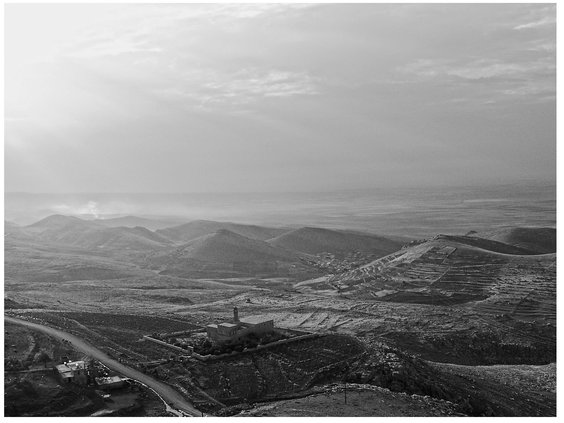

The Upper Mesopotamian plain viewed from the Tur Abdin Mardin.

Dominik Bonatz

Introduction

This volume presents the proceedings of an international workshop entitled The Archaeology of the Upper Mesopotamian Piedmont in the Second Millennium BC , which was held from 21 to 22 January 2010 within the framework of the Topoi Excellence Cluster at the Freie Universitt Berlin. One of the main goals in organizing this workshop was to privilege discussions in which scholars could exchange and confront results of recent archaeological research in the upper Mesopotamian piedmont regions. When the outcomes of the discussion were summarized, the question of political space(s) arose as a central topic for almost all of the papers collected here. This introductory piece therefore has the two-fold aim of describing the background of archaeological research in the upper Mesopotamian piedmont and providing a starting point for further discussion of the creation of political space(s) in this area and beyond.

The landscape

Visitors to the old city of Mardin, situated on the high ridge of the Anatolia, are inevitably attracted to the spectacular views of the broad panorama of the upper Mesopotamian piedmont. They are enchanted by the abrupt changes in the landscape and realize that a new geographical horizon is opening before their very eyes. Here lies the gateway to Greater Mesopotamia, the millennia-old heartland of agriculture, cities, and political changes.

The scenic character of the upper Mesopotamian plain immediately south of the Tur Abdin/Maz Da mountain range changes throughout the year: it is sprinkled with snow in winter, a lush green in spring, and finally a dusty yellow in summer. Climatic conditions in this area are very favourable for human life. Annual precipitation is usually sufficient to ensure agriculture without irrigation, and the many karst springs guarantee a year round supply of water. Several small tributaries emerging from these springs create the triangular-shaped catchment area of the upper Jazirah. This region is currently divided by the Turkish-Syrian border, but in the past it formed a single geographic zone in which one of the longest and most dynamic cultural sequences of the Ancient Near East developed.

When weather conditions are clear, the steep mountains of Tur Abdin/Maz Da which form a distinct geographic barrier in the direction of the Anatolian highlands can be viewed from many mounds in the Khabur headwater region. From a Mesopotamian perspective, however, this mountain range has apparently never been perceived as the worlds end. Instead, it was seen as an invitation to cross the border and explore the richness of resources hidden beyond. As early as the 13th century BC, Assyrian sources mention the Kaiyari Mountains identical with the Tur Abdin and provide a vivid glimpse of the efforts to gain access to this region (Radner 2006). One of the most convenient routes, still used today, runs along the Tigris valley, which actually forms another piedmont zone sandwiched between the northern slopes of the Tur Abdin and the foothills of the eastern Tauros.

The upper Khabur Triangle were on the crossroads of the routes connecting the Anatolian mountains with the Mesopotamian plains. They were highly important for early trade networks and drew larger polities which aimed to extend their economic resources and political power.

Political space(s)

Mittani state in the middle, and the Middle Assyrian state at the end.

However, historical records tend to be fuzzy and imprecise when they are used to identify the concrete limits of political spaces. A well-known example is the Middle Assyrian designation Land of Hanigalbat (mtanigalbat), apparently applied to those territories that were conquered within the Mittani realm in the 13th century, but the geographical scope of this desigantion is hard to determine (Harrak 1987; Szuchman 2009). Although administrative texts found in the capital Assur and some provincial sites show that this huge western part of the empire was organized into numerous districts ( pahutu ), it is impossible to describe the size of the individual districts and their overall pattern in the landscape (Jacob 2003). As a result, two further approaches are required one heuristic and the other empirical in order to identify the political spaces in these distinct geographic areas. The methodology must take into account the archaeological data or hard facts which primarily originate from the area under investigation.

To start with the heuristic approach, one important question is what distinguishes political space from political landscape. In The Political Landscape (2003) Adam T. Smith has cogently disentangled the oft-conflated concepts of space, place, and landscape. He defines landscape as a concept arising in the historically rooted production of ties that bind together spaces, places, and representations (Smith 2003, 11). The political within this concept is described as a set of relationships central to the production, maintenance, and overthrow of sovereign authority ( ibid. ). Hence, political and landscape mainly relate to each other in sociological terms. Within the concept of space, however, the meaning of the political lies in its specific forms of delimiting physical experience. Subjects are bound to the interests of political regimes through spatial relations that cannot be infinite but need to be framed by ideologies and their materializations (DeMarrais / Castillo / Earle 1996).

Political space is articulated in many different ways. It can be characterized in terms of the actual patterns of provision of governance in areas of widespread interest and salience (Jones 2002, 228). This has been termed the supply side of political governance in which we locate any exercise of political power such as communication networks, technologies, and built environments. For archaeologists, it seems that the supply side provides a good starting point for investigations into the structures of political governance in ancient civilizations. As for the analytic equation, the demand side which refers to patterns in the need forgovernance ( ibid. ) is ultimately hard for archaeologists to identify. Furthermore, it should be stressed that political space need not necessarily be connected to the authority of a state since the existence of autonomous political space formed in the absence of a state is a rather common occurrence in the history of political space(s) (Dark 2002, 6265). Hence the shifting relationships between politically active groups, geographic environments, and territories may provide another clue for understanding the formation of political space(s) in the past. What contribution can archaeology make to such an approach?