Published in 2014 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2014 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2014 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to http://www.rosenpublishing.com.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J. E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Hope Lourie Killcoyne: Executive Editor

Vincent Hale: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Brian Garvey: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hale, Vincent.

Mesopotamian gods & goddesses/edited by Vincent Hale -- 1st ed.

p. cm.(Gods & goddesses of mythology)

Includes index and bibliography.

ISBN 978-1-62275-162-4 (eBook)

1. Mythology, Assyro-BabylonianJuvenile literature. 2. Civilization, Assyro-BabylonianJuvenile literature. I. Title.

BL1620.H35 2014

299d23

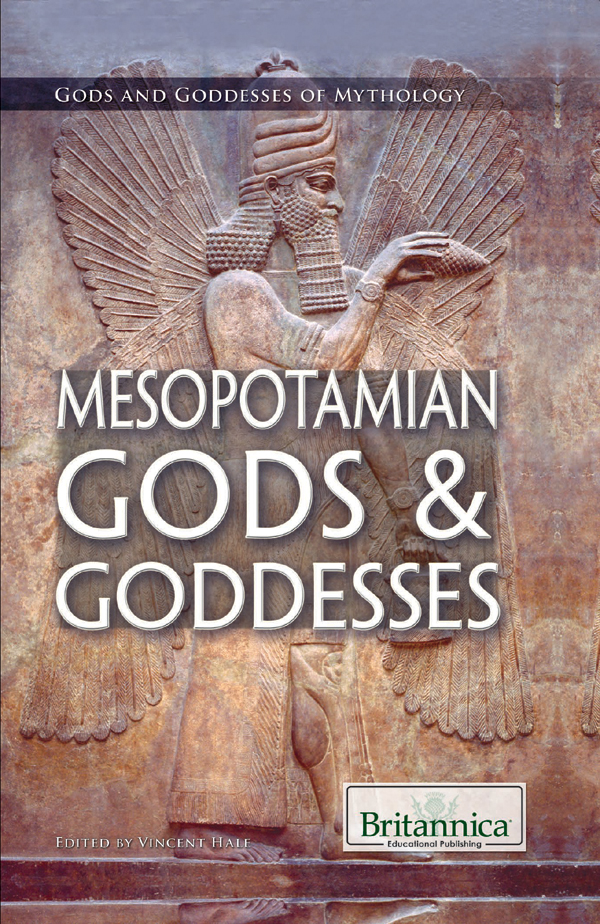

On the cover:Relief of Mesopotamian god Marduk. jsp/Shutterstock.com

Interior pages (cuneiform) khd/Shutterstock.com; back cover iStockphoto.com/DavidMSchrader

Contents

Assyrian wall illustration bearing cuneiform script. khd/Shutterstock.com

M esopotamian religion and mythology were the beliefs and practices of the Sumerians and Akkadians, and their successors, the Babylonians and Assyrians, who inhabited ancient Mesopotamia (now in Iraq) in the millennia before the Christian era. These religious beliefs and practices form a single stream of tradition. Sumerian in origin, Mesopotamian religion was added to and subtly modified by the Akkadians (Semites who emigrated into Mesopotamia from the west at the end of the 4th millennium BCE ), whose own beliefs were in large measure assimilated to, and integrated with, those of their new environment.

As the only available intellectual framework that could provide a comprehensive understanding of the forces governing existence and also guidance for right conduct in life, religion ineluctably conditioned all aspects of ancient Mesopotamian civilization. It yielded the forms in which that civilizations social, economic, legal, political, and military institutions were, and are, to be understood, and it provided the significant symbols for poetry and art. In many ways it even influenced peoples and cultures outside Mesopotamia, such as the Elamites to the east, the Hurrians and Hittites to the north, and the Aramaeans and Israelites to the west.

The genre of myths in ancient Mesopotamian literature centres on praises that recount and celebrate great deeds. The doers of the deeds (creative or otherwise decisive acts), and thus the subjects of the praises, are the gods. In the oldest myths, the Sumerian, these acts tend to have particular rather than universal relevance, which is understandable since they deal with the power and acts of a particular god with a particular sphere of influence in the cosmos. An example of such myths is the myth of Dumuzis Death, which relates how Dumuzi (Producer of Sound Offspring; Akkadian: Tammuz), the power in the fertility of spring, dreamed of his own death at the hands of a group of deputies from the netherworld and how he tried to hide himself but was betrayed by his friend after his sister had resisted all attempts to make her reveal where he was.

A carved stone vessel known as the Uruk Vase, illustrating the Sumerian goddess Inanna, located in the city of Uruk in modern-day Iraq. Marc Deville/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

A similar, very complex myth, Inannas Descent, relates how the goddess Inanna (Lady of the Date Clusters) set her heart on ruling the netherworld and tried to depose her older sister, the queen of the netherworld, Ereshkigal (Lady of the Great Place). Her attempt failed, and she was killed and changed into a piece of rotting meat in the netherworld. It took all the ingenuity of Enki (Lord of Sweet Waters in the Earth) to bring Inanna back to life, and even then she was released only on condition that she furnish a substitute to take her place. On her return, finding her young husband Dumuzi feasting instead of mourning for her, Inanna was seized with jealousy and designated him that substitute. Dumuzi tried to flee the posse of deputies who had accompanied Inanna, and with the help of the god Utu (Sun), who changed Dumuzis shape, he managed to escape, was recaptured, escaped again, and so on, until he was finally taken to the netherworld. The fly told his little sister Geshtinanna where he was, and she went in search of him. The myth ends with Inanna rewarding the fly and decreeing that Dumuzi and his little sister could alternate as her substitute, each of them spending half a year in the netherworld, the other half above with the living.

A third myth built over the motif of journeying to the netherworld is the myth of The Engendering of the Moongod and His Brothers, which tells how Enlil (Lord of the Air), when still a youngster, came upon young Ninlil, the goddess of grain, as sheeager to be with child and disobeying her motherwas bathing in a canal where he would see her. He lay with her in spite of her pretending to protest and thus engendered the moon god Su-en (Sin). For this offense Enlil was banished from Nippur and took the road to the netherworld. Ninlil, carrying his child, followed him. On the way Enlil took the shape first of the Nippur gatekeeper, then of the man of the river of the netherworld, and lastly of the ferryman of the river of the netherworld. In each such disguise Enlil persuaded Ninlil to let him lie with her to engender a son who might take Su-ens place in the netherworld and leave him free for the world above. Thus, three additional deities, all underworld figures, were engendered: Meslamtaea (He Who Issues from Meslam), Ninazu (Water Knower), and Ennugi (the Lord Who Returns Not). The myth ends with a paean to Enlil as a source of abundance and to his divine word, which always comes true.

Most likely all of these myths have backgrounds in fertility cults and concern either the disappearance of natures fertility with the onset of the dry season or the underground storage of food.

As Enlil is celebrated for engendering other gods that embody other powers in nature, so also was Enki in the myth of Enki and Ninhursag, in which Enki lay with Ninhursag (Lady of the Stony Ground) on the island of Dilmun (modern Bahrain), which had been allotted to them. At that time all was new and fresh, inchoate, not yet set in its present mold. There Enki provided water for the future city of Dilmun, lay with Ninhursag, and left her. She gave birth to a daughter, Ninshar (Lady Herb), on whom Enki in turn engendered the spider Uttu, goddess of spinning and weaving. Ninhursag warned Uttu against Enki, but he, proffering marriage gifts, persuaded her to open the door to him. After Enki had abandoned Uttu, Ninhursag found her and removed Enkis semen from her body. From the semen seven plants sprouted forth. These plants Enki later saw and ate and so became impregnated himself. Unable as a male to give birth, he fell fatally ill, until Ninhursag relented andas birth goddessplaced him in her and helped him to give birth to seven daughters, whom Enki then happily married off to various gods. The story is probably to be seen as a bit of broad humour.