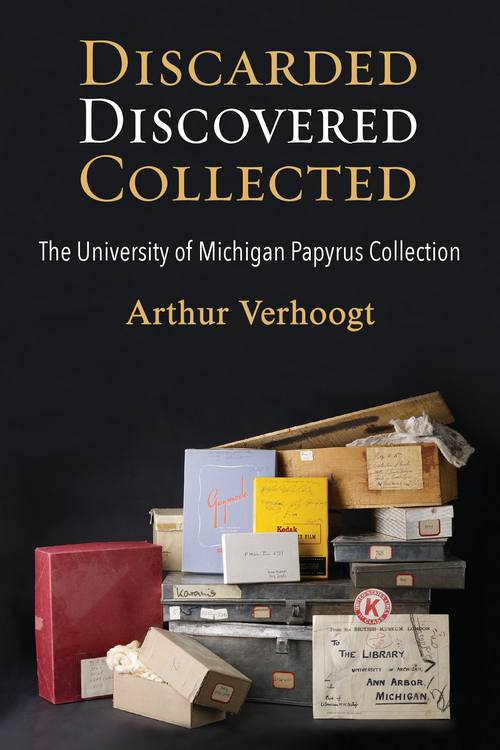

Discarded, Discovered, Collected

Discarded, Discovered, Collected

The University of Michigan Papyrus Collection

Arthur Verhoogt

University of Michigan Press

Ann Arbor

Copyright 2017 by Arthur Verhoogt

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States of America by the

University of Michigan Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Verhoogt, A. M. F. W. (Arthur M. F. W.), author.

Title: Discarded, discovered, collected : the University of Michigan papyrus collection / Arthur Verhoogt.

Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017011110| ISBN 9780472073641 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780472053643 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780472123162 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: University of Michigan. Library. Papyrology Collection. | Manuscripts (Papyri)

Classification: LCC PA 3343 . V 47 2017 | DDC 808.80074/77435dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017011110

Publication made possible in part through the support of Virginia and William Dawson.

Contents

Visitors to the University of Michigan papyrus collection often ask whether there is a book about the collection. Until now, this question had to be answered negatively, although I would always refer patrons to the website of the collection (http://www.lib.umich.edu/papyrus-collection), where much information can be found. This answer satisfied some, but not all, and in discussions with the then collection manager, Adam Hyatt, we agreed that a book like the one you are holding now would be a good idea.

This book presents the history, scholarship, and impact of the University of Michigan papyrus collection with the help of some 40 texts from that collection. It will provide readers with an opportunity to actively discover something about the ancient world themselves through looking at and reading texts from the Michigan papyrus collection. It is my hope that this presentation will convey some of the excitement that comes with dealing with original documents from the ancient world that is felt by everybody who visits the papyrus collection. What I was looking for in writing this book is to provide a written version of what it is like to visit the papyrus collection for a tour.

In a way, what follows is my interpretation of the University of Michigan papyrus collection rather than its objective presentation. In selecting the texts to present and discuss, I have taken into account what visitors to the collection are always intrigued by, but I have also included some lesser-known texts from the collection that I find interesting. Many readers will point at gaps in what this book covers. One significant gap in this book is late antiquity. This is unfortunate, because the collection includes a number of interesting and worthwhile texts from this important period in Egyptian history. The main reason for not including them is that I am not a specialist in Byzantine Egypt. Another issue with Byzantine papyri is that the more interesting ones are very long and difficult to incorporate in the vision I had of this book, which privileges breadth and diversity over exhaustive coverage of any single text. The online database of the collection allows anybody to search for texts that she is interested in and that are not covered in this book or to find out even more about the ones that are.

The field of papyrology was among the first to adopt the possibilities of the digital age starting in the early 1990s, when the Duke Database of Documentary Papyri (DDbDP) was first developed. Papyrology has continued to be at the forefront of digital humanities with numerous online projects. In this light, it may seem old-fashioned to present the Michigan papyrus collection in a printed book form. However, it will soon become clear to the reader that this book does not stand apart from the online world of papyrology but provides a gateway into it.

This book builds on the contributions of numerous scholars who worked in the Michigan papyrus collection. It is a tribute to their hard work and at the same time an invitation to others to come and study the riches of the Michigan papyrus collection.

The idea for this book took shape between 2010 and 2013 when I served as acting archivist for the Michigan papyrus collection after the unexpected death of Traianos Gagos in April 2010. During those years, I had a great team to work with, and I am grateful for their support. In the first year, Peggy Daub and Shannon Zachary provided a much needed connection with the library administration, while graduate students R. James Cook and Adam Hyatt did the day-to-day work to keep the collection running. I am much obliged to the collection managers, first Adam Hyatt and then Monica Tsuneishi. The latter has been instrumental in making sure that this book includes illustrations and charts.

Several people read the manuscript in various stages and added their expertise. I am very grateful for the friendship, good cheer, and support of the current archivist of the collection, Brendan Haug, during the long process of this books genesis. Henrike Florusbosch edited the whole manuscript in its final stages and made sure that it all made sense. I want to acknowledge Shannon Zachary, head of the Library Conservation Department, who read through the entire manuscript in an early stage. Library conservators Leyla Lau-Lamb (now retired) and Marieka Kaye commented on drafts for chapter 3. Randal Stegmeyer made most of the images included in this book. He was also kind enough to comment on the section in chapter 4 that describes the various photographic techniques.

I am fortunate to have a wonderful group of friends, colleagues, and students at the University of Michigan and elsewhere. Terry Wilfong read through parts of the manuscript and I was once again impressed with his sensitive editorial eye. He also kindly gave me permission to use the translation of his forthcoming edition of the Book of the Dead (fig. 6.1). I am grateful to Graham Claytor and Lizzie Nabney for reading parts of the manuscript and making detailed suggestions for its improvement. In Leiden, my Doctor-buddy Koen Donker van Heel once again came to my rescue when I was stuck in a Demotic text and provided the translation for figure 6.2. Rob Sier kept me focused by consistently asking the right question: What would be first, this book or the next national soccer championship for AZ Alkmaar? I won.

At the University of Michigan Press I am grateful to Ellen Bauerle who ever so cheerfully kept me on track for this book project when other equally interesting projects interfered. She was responsible for finding the two anonymous reviewers who provided the kind of feedback that makes books better, and I am grateful to them both for taking the time to do so.

I did most of the writing for this book during the 2014/15 academic year when I was a Fellow-in-Residence at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in Wassenaar. I wish to thank its staff and all my fellow fellows for creating a productive environment in which to work. In particular, I am grateful to Marwan Kraidy, Mark Moritz, and Diederik Oostdijk for stimulating discussions about the art of writing in our very different disciplines.

Next page