Blacksmithing

Projects

Blacksmithing

Projects

Percy W. Blandford

Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, New York

Copyright

Copyright 1988 by Percy W. Blandford

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2006, is an unabridged republication of 24 Blacksmithing Projects, originally published by Tab Books Inc., Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania, in 1988.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Blandford, Percy W.

Blacksmithing projects

p. cm.

Originally published: 24 blacksmithing projects. Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Tab Books, c1988.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-486-45276-X (pbk.)

1. Blacksmithing. I. Blandford, Percy W. 24 blacksmithing projects. II. Title.

TT220.B42 2006

682dc22

2006046819

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501

Introduction

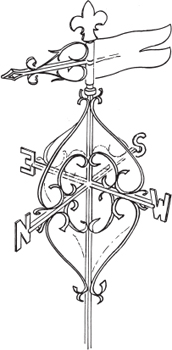

Blacksmithing is one of the oldest crafts. Ever since man discovered how to produce iron he has worked it hot into useful and decorative things. The techniques of the craft have changed little over thousands of years and a modern blacksmith, whether professional or amateur, carries on the tradition in ways that a blacksmith of earlier times would recognize.

In industry today much metalwork is done by machinery. Mass-produced items have a superficial resemblance to the products of a traditional blacksmith, but they lack the individuality of a hand-forged piece of metalwork. The traditional blacksmith often combined his skill with that of the farrier, in shoeing horses. This is now a very specialized craft, and not one that would be lucrative sparetime work.

The modern blacksmith may use a forge with a hand or electric blower, or rely on propane or other gas for heating. For work requiring heat over a large area, a coal-burning forge cannot be equaled, but it is possible to make a large range of projects with the more limited heat from gas flames. The same applies to tools. You will need the anvil and basic hand tools, but with a few more general metalworking toolsparticularly a drill press or hand electric drilla great many interesting, useful, and decorative articles may be made with comparatively limited resources.

What to make might sometimes be a puzzle. This book is intended to offer ideas that are complete in themselves, but that can also be modified to your needs or act as starting points for articles you can finish differently. The projects described range from those that can be made with few tools, improvised equipment, and a single propane torchto others that will require all the skill and equipment of an experienced smith. Blacksmithing is a skill that requires coordination of brain and hands. Only practice brings the ability to fashion steel into the forms you want. Anyone still learning should select fairly easy projects and concentrate on producing the best possible results, then move on to more advanced work, still aiming for quality in the finished product. In that way, the traditions of this long-standing craft will be carried on through another generation.

This is an idea book, not instruction on blacksmithing techniques. The book is complete in itself, but anyone requiring instructions in craft and methods of blacksmithing should refer to the authors Practical Blacksmithing and Metalworking, Second Edition (Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania: Tab Books, 1988).

Blacksmithing

Projects

Set of Punches and Chisels

A metalworker, whatever the particular branch of metalwork that interests him or her, needs a variety of punches and chisels. It might seem that there is never a large enough variety, that there are always different sizes and shapes that would suit a particular job better. Some of these tools also have uses, as they are or slightly modified, in working wood, leather, stone, and other materials. The blacksmith is able to make all these tools for his own or other craftsmens use, even if his equipment is not as comprehensive as he would like. It should be possible to make most of the tools in this project with only a propane torch as a source of heat and an iron block as an anvil.

The material is high-carbon steel, which may be round, square, octagonal, hexagonal, or almost any other rod section. It need not be new and can be salvaged from discarded tools, springs, and similar things. Some commercially produced punches and chisels are made from special alloy steels. They need precise heat treatment unavailable to most individual blacksmiths, so these steels are better avoided. Ordinary high-carbon steel can be hardened and tempered satisfactorily with simple equipment.

A few punches, but not cutting tools, can be made from mild steel, which cannot be hardened and tempered, because it is unaffected by cooling in water. Remember not to do this with high-carbon steel; cooling in this way not only hardens it, but makes it brittle. Until you intentionally harden the steel it should be allowed to cool slowly.

Although short pieces of rod can be held with tongs, it is always easier to work on the end of a long rod, which can be held and then cut off. Where possible, do not cut the steel to length until after shaping its end.

If you wish to make something from high-carbon steel that has previously formed something else, it is advisable to anneal it to remove its temper and make it as soft and ductile as possible before reforging it. This is done by heating to redness and allowing to cool as slowly as possible. Leaving it in a fire overnight to cool is a good way of achieving ultimate softness.

A simple project is a center punch () to minimize spreading when being hammered.

File or grind the tapered part to a bright finish. Finishing with emery or other abrasive cloth can follow, because the better the surface polish, the easier it is to see oxide colors when tempering.

Start from the end and heat about 1 inch to redness. Hold with tongs and plunge vertically into water (). Be careful not to let the steel go in at an angle, which might cause cracking. Brighten the end again with abrasive cloth. This could not be done if it had not been previously polished; because the point would be very hard and brittle.

To temper, use a propane torch () or similar flame and heat between 1 and 2 inches from the point. Watch the spread of oxide colors towards the point. Heat will continue to spread, even when you take the flame away. The slower the heat, the greater the widths of the oxide colors, and the greater the width of steel at a particular temperature. The first color to reach the end will be a pale straw, which will deepen. When it has passed through dark straw to brown, plunge the point vertically into water. That should give a suitable hardness for a center punch.

An alternative method requires quicker action, but with only one heating. Have the tapered part bright and heat to redness as before, but only plunge a short distance into water. While the steel is still hot higher up, brighten the last inch and watch the spread of colors from the hot part. When you get the correct color, quench the steel completely.

If you let the colors go too far with either method, return to hardening before trying to tempter again. Most high-carbon steels can be hardened and tempered in water at room temperature. Some are intended to be quenched in brine (saturated salt solution) and some in oil. If you buy new steel, the supplier will indicate what to use. If you are re-using steel, and water causes the steel of a test piece to crack, use one of the other liquids.

Next page