PRACTICAL BLACKSMITHING

Compiled and Edited by

M.T. Richardson

CONTENTS

Guide

FOREWORD

By hammer and hand, all the arts do stand.

The author of the above quote is unknown, and the profound truth captured in those nine words escaped me on first reading. Yet the veracity of this proverb, after a moment of contemplation, is undoubtedly true. True at least for the industrial and mechanical arts. Recognizing the hammer as a foundational aspect of the human experience, seeing its vital contribution to the advancement of society, is reason enough to justify this reprinting.

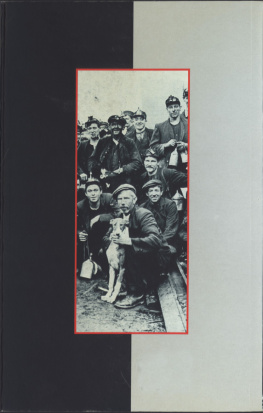

Drawn from the pages of the monthly journal, The Blacksmith and Wheelwright, the narratives, the detailed drawings and instructions contained herein not only recall the past developments of the trade but can serve as guide and inspiration in the present. The ancient and venerable skills described in these four volumes often served to meet an existential need. They paved the way for progress and efficiency. The purely functional aspects of metal working were, for our forebearers, of critical importanceeven a matter of life and death. Through Richardsons Practical Blacksmithing, we recall the role of the blacksmith in matters of war. The development of weapons, armor, and chainmail are detailed. Many lives, those saved and those lost, might well have depended on the quality of workmanship at the forge and anvil. Beyond such deadly results wrought by man we remember the hammer, the sickle, the plow, the horseshoe and more that allowed a new freedom and means of survival for communities across the globe.

My own journey into this ancient and historic world began in 1978. The mainstream and standard world of the so-called professions seemed to me a prison sentence. I found myself in search of meaningful and fulfilling work, work not for anothers profit, but work that might allow me to meet my own needs on my own terms. This very book, then in a newly released edition, helped me find my way.

Through these pages, I entered a world steeped in history and practical knowledge. As I read, I found there is a kind of poetry and delicacy of expression nestled beside technical drawings and metallurgical science. I found the book to be beautifully illustrated, brimming with creative ideas; all gathered and presented to the reader on a scale available nowhere else.

To my surprise, there is often an unexpected and dry sense of humor woven throughout these pages. I recall, for example, the frustration of a poorly functioning grinding stone, a stone that must be wetted down to prevent glazing, is delightfully captured in Volume Two. Water has a decided tendency to disassociate itself from a stone that capers about too lively, thereby giving the smith an unwanted soaking.

For the lover of the metal arts, or the student of history, for the collector of antiques, for the professional, or the weekend enthusiast there is something of value to be discovered. I encourage you to enjoy connecting to a long line of working men, joined today by working women blacksmiths, who found fulfillment at the anvil. Those who then and now, in their own small way, changed their lives and the world through the art and science of blacksmithing.

Bob Weick

Philadelphia, 2017

INTRODUCTION

Some time since, Mr. G. H. Birch read a paper before the British Architectural Association entitled: The Art of the Blacksmith. The essential portions of this admirable essay are reproduced here as a fitting introduction to this volume:

It is not the intention of the present paper to endeavor to trace the actual working of iron from primeval times, from those remote ages when the ever-busy and inventive mind of man first conceived the idea of separating the metal from the ore, and impressing upon the shapeless mass those forms of offense or defense, or of domestic use, which occasion required or fancy dictated.

Legends, both sacred and profane, point retrospectively, the former to a Tubal Cain, and the latter to four successive ages of gold and silver, brass and iron. Inquiry stops on the very edge of that vague and dim horizon of countless ages, nor would it be profitable to unravel myths or legends, or to indulge in speculation upon a subject so unfathomable. Abundant evidence is forthcoming not only of its use in the weapons, utensils and tools of remote times, but also of its use in decorative art; unfortunately, unlike bronze, which can resist the destructive influence of climate and moisture, ironwhether in the more tempered form of steel or in its own original statereadily oxidizes, and leaves little trace of its actual substance behind, so that relics of very great antiquity are but few and far between. It remains for our age to call in science, and protect by a lately discovered process the works of art in this metal, and to transmit them uninjured to future ages. In the

RETROSPECTIVE HISTORY OF THE BLACKSMITHS ART

no period was richer in inventive fancy than that period of the so-called Middle Ages. England, France, Italy, and more especially Germany, vied with each other in producing wonders of art. The anvil and the hammer were ever at work, and the glow of the forge with its stream of upward sparks seemed to impart, Prometheus-like, life and energy to the inert mass of metal submitted to its fierce heat. Nowhere at any period were the technicalities of iron so thoroughly understood, and under the stalwart arm of the smith brought to such perfection, both of form and workmanship, as in Europe during this period of the Middle Ages.

The common articles of domestic use shared the influence of art alike with the more costly work destined for the service of religion; the homely gridiron and pot-hook could compare with the elaborate hinge of the church door or the grille which screened the tomb or chapel. The very nail head was a thing of beauty.

Of articles for domestic use of a very early period handed down to our times we have but few specimens, and this can easily be accounted for. The ordinary wear and tear and frequent change of proprietorship and fashion, in addition to the intrinsic value of the metal, contributed to their disappearance. New lamps for old ones, is a ceaseless, unchanging cry from age to age. In ecclesiastical metal-work, of course, the specimens are more numerous and more perfectly preserved; their connection with the sacred edifices which they adorned and strengthened proved their salvation.

IRON TO PROTECT THE HUMAN FORM.

Without going very minutely into the subject of arms and armor, it is absolutely necessary to refer briefly to the use of iron in that most important element, in the protection of the human form, before the introduction of more deadly weapons in the art of slaying rendered such protection useless. In the Homeric age such coverings seem to have been of the most elaborate and highly wrought character, for, although Achilles may be purely a hypothetical personage, Homer, in describing his armor, probably only described such as was actually in use in his own day, and may have slightly enriched it with his own poetic fancy. From the paintings on vases we know that sometimes rings of metal were used, sewn on to a tunic of leather. They may have been bronze, but there is also every reason to believe that they were sometimes made of iron. Polybius asserts that the Roman soldiers wore chain-mail, which is sometimes described as