Chapter 1: Understanding Blacksmithing Basics

A Brief History of Blacksmithing

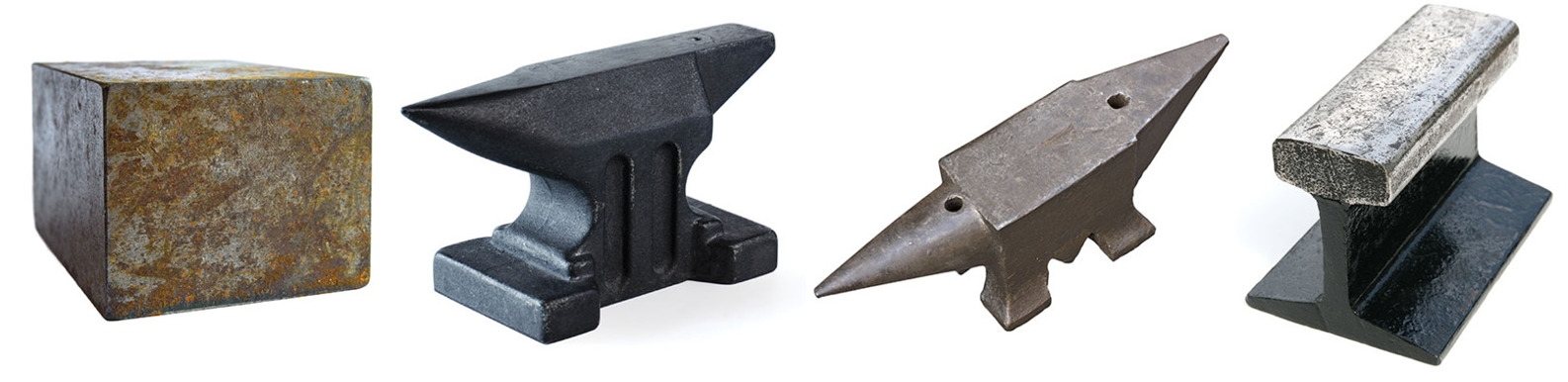

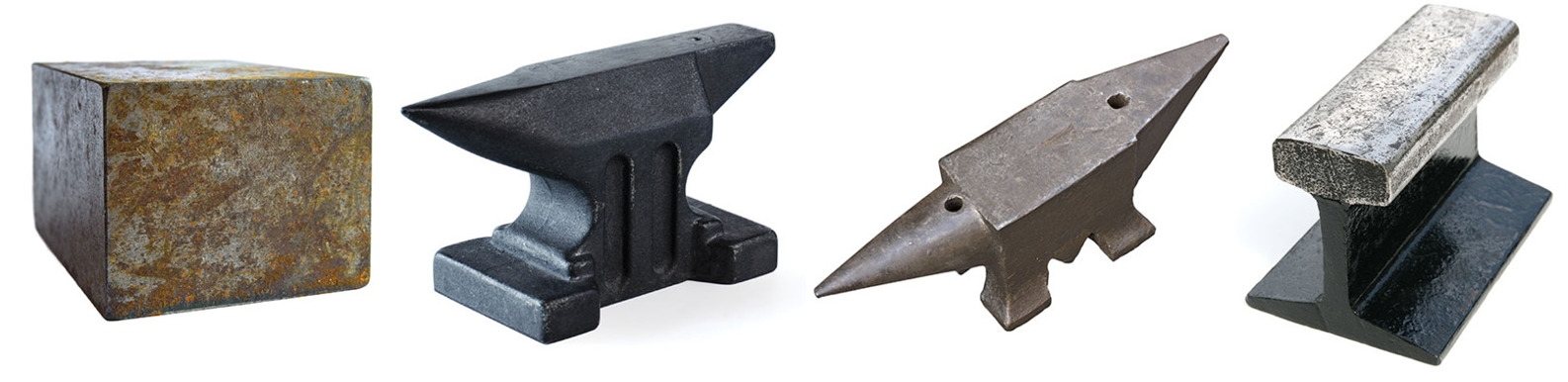

For new blacksmiths, knowing how our craft has evolved is extremely important in helping you set up your first forge without a lot of cost and time spent looking for materials. Ask a number of blacksmiths from around the world what the tools in a blacksmiths forge should look like, and you will get a dozen different answers. This is because, over time, blacksmithing tools have evolved differently in different parts of the world. Ask a North American or European smith what an anvil should look like, and he or she will describe a stereotypical London-pattern anvil with a horn and a heel, straight from the cartoons. At the same time, an Asian smith may say that it is simply a square block of steel. If you went back to the Middle Ages, a European smith would give you the same answer as the Asian smith. Go back even further and any smith would point to a large, flat rock.

Today, beginner Western blacksmiths get caught up trying to find a London-pattern anvil, thinking that it is the only style of anvil that will work. This often leads to frustration, which can further lead a blacksmith to either purchase an inferior cast-iron anvil from the local welding shop or spend too much money when a simple block of steel would work. Others will spend more time looking for a good piece of railway steel, which has become the ubiquitous makeshift beginner anvil. I have used everything from Peter Wright and Hay-Budden anvils to simple steel cutoffs and hydraulic shafts stood on end. The railway anvils I have used are often as bad as cast iron because they dont have the proper mass underneath the hammering surface to support heavy forging, instead flexing and absorbing too much of your hammers blow.

I discuss in more detail what to look for in an anvil in a later chapter, but I feel that a little blacksmithing history will help you choose your tools more easilyalong with the understanding that it isnt the tools that make you a blacksmith, but rather the techniques. Blacksmiths tools have changed with the need for and availability of fuel, iron, and science. Your forge can be the same: an evolution based on necessity and availability.

By around 1200 BC, iron was becoming the principal metal for tools and weapons, with some overlapping of the Bronze Age. Prior to this time, iron artifacts were scarce as different cultures experimented with the newly discovered technology. While iron is stronger and makes longer lasting tools, it was slow to become a commonly used metaland eventually overtake bronzebecause it was more difficult to produce iron from its rock ore, and it needed higher temperatures to work. Eventually, civilizations advanced their iron-smelting technologies and began using iron for more items, including art. Iron improved a societys production, agricultural, and warfare abilities, and the blacksmith was considered the king of craftsmen because he created the tools for all other trades.

Each area of the world started forging iron with similar tools, likely either rocks or bronze hammers and the same anvils or boulders that they had been using to work bronze and copper. Until relatively recently, in the grand scheme of things, blacksmiths used blocks of steel or stake anvils and hammers that were fairly similar. Around the 1600s, Western European blacksmiths began to develop an anvil shape that most smiths are familiar with: the London or Continental pattern anvil. Unfortunately, this change from centuries past creates many issues for new blacksmiths today because usable antique anvils are hard to find and can be expensive, while good-quality new anvils are even more expensive. All the while, the original anvil shapea simple block of steelsits in the scrap yard, waiting to be melted down and recycled.

The forge is another part of the blacksmiths shop that has changed significantly over the past centuries, both in design and in fuel source. An early forge was simply a fire pit fueled by charcoal, and the air supply was likely a pair of leather sacs opened and closed by the blacksmiths assistant, with a wooden or reed pipe connecting the bellows to the fire pit. Over time, this side-draft forge was raised off the ground, and different styles of bellows evolved in different regions.

Eventually, as coal became a more prevalent fuel, bottom-blast forges with blast pipes (tuyeres), known as duck-nest tuyeres, became more common and were often sold in mail-order catalogs. Modern blacksmiths now have access to other forge fuels, such as propane and acetylene, as well as electric induction. Later in the book, I will go deeper into the different forge fuels and how to make your own charcoal so that you dont waste time and money trying to find and buy blacksmithing coal.

Historically, blacksmiths forged pure iron, known as wrought iron . Wrought iron was created from iron ore with very little added carbon. These days, it is difficult to purchase pure wrought iron, so most blacksmiths use what is known as mild steel , a low-carbon steel alloy. Because of this, many smiths use the term iron for mild steel because it has replaced pure wrought iron as the most common metal for blacksmithing. This terminology allows for a differentiation between steel , which has enough carbon to harden properly for tools, and mild steel, which will not harden. Because you will be making your own tools for the forge and around the house and farm, this is an important distinction.

Now that you are armed with a brief history of what tools and fuels blacksmiths commonly used in the past, we can move on to understanding how metal moves. Once you understand how metal behaves when its forged, you can find many unconventional tools in scrap yards, just like the blacksmiths of old had to.

Same Techniques, Different Times

Realizing that blacksmithing is about the techniques, not the tools, will make setting up your first shop much easier. While the tools may have changed over the years, the techniques that blacksmiths use have remained the same.

Did You Know?

Use chilled modeling clay to practice the different forging techniques or when starting a new project. It will save money on fuel and iron because it can be reshaped and reused.

The Physics of Moving Metal

Before we get into finding tools and the actual techniques of blacksmithing, it will be helpful to look at how iron behaves when forged, so that we can start to understand how the variously shaped tools move metal. By learning how shapes, rather than specific tools, move metal, your eyes will be opened as you wander through your local scrap yard. In my experience, most beginning blacksmiths end up reading a beginners blacksmithing book that leads off with a description of the tools in a typical post-1800s blacksmith shop that used coaland then the new blacksmith spends all of his or her time searching for the tools in the book. Instead, new blacksmiths need to understand how metal can be controlled and then find the tools that have the shapes to do it. This makes setting up a shop much easier.

The great thing about iron is its immense strength when cool and its plasticity at higher temperaturesif you heat iron hot enough in a fire, it moves like clay and can be molded easily by a hammer and anvil. Because hot iron moves like clay, a great way to practice without wasting metal is to chill modeling clay in a refrigerator and then shape it into rods of iron to forge.

The tools that you use as a blacksmith have two types of shapes: shapes that force metal outward uniformly or shapes that move metal in two directions. Shapes that are uniform in all directions, such as a full-faced hammer or the peen on a ball-peen hammer, push the metal out in all directions. A fuller is any wedge-shaped tool that pushes the metal in two directions.

Next page