Contents

Promoting Inclusion

and Diversity in

Early Years Settings

A Professional Guide to Ethnicity,

Religion, Culture and Language

Chandrika Devarakonda

Contents

Introduction

Migration and globalisation have resulted in increased diversity of the population in many developed countries (Nargis and Tikly, 2010). The increase in migration into Europe, which includes families with young children, is due to a range of factors, including economic migration, people seeking asylum and/or those fleeing political unrest or war (refugees) (Nargis and Tikly, 2010). The rapid change in social, cultural and political context in the receiving countries like the United Kingdom and other European countries implies that early years and primary education settings are highly diverse and exceedingly culturally rich learning communities (Nargis and Tikly, 2010). For example, in England, net migration in 2018 showed an increase of 29 per cent over the previous 15 years (DfE, 2018). This led to an increase in the diversity of pupils, from the perspective of their ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religious backgrounds and English as an additional language in primary and secondary schools (Nargis and Tikly, 2010). This has resulted in an additional expectation on teachers to acknowledge and identify the diverse and unique needs of all children. Further, teachers will have to understand the need to relate to and appreciate the diverse backgrounds of the pupils in the classroom and provide opportunities to include them. But do teachers feel prepared to teach in diverse settings?

Diversity refers to children who are from different contexts and backgrounds and have different needs and abilities. This includes ethnicity, gender, age, disabilities, race, religion, Gypsy, Roma and Traveller families and other categories. Paine (1990) proposed four categories of diversity perceived as layers:

individual differences relating to biological and psychological dimensions such as being tall, shy, etc.

categorical differences belonging to specific categories such as class, ethnicity and gender

contextual differences defined by social contexts and are socially constructed

pedagogical view of difference relating to how the differences found in individuals and groups have implications on their teaching and learning experiences.

UNESCO highlighted diversity in its definition of inclusion:

as a process of addressing and responding to the diversity of needs of all learners through increasing participation in learning, cultures and communities, and reducing exclusion within and from education. It involves changes and modifications in content, approaches, structures and strategies, with a common vision which covers all children of the appropriate age range and a conviction that it is the responsibility of the regular system to educate all children. (2005, p.13)

Promoting inclusion and diversity means acknowledging and respecting differences. Diversity can be promoted through a set of conscious practices that involve:

understanding that the needs of people belonging to specific groups are not homogenous

mutual respect for people and experiences that are different

recognising that individual and institutionalised discrimination will result in privileges for some while others are disadvantaged

building bridges, which can eliminate all forms of discrimination.

Examples of categories related to diversity in a community related to children and families:

Gender | Race | Ethnicity | Culture |

EAL | Socioeconomic status | Area of residence | Levels of education of parents |

Looked after child | Foster care/adopted | Ability/disability | Migrant/refugee/asylum seeker |

Country of origin | Age | Religion |

Sometimes, children are assigned a label and are considered disadvantaged or vulnerable as a result of stereotyping. The needs of children cannot be assumed based on their visible characteristics. For example, all White children are not privileged and advantaged.

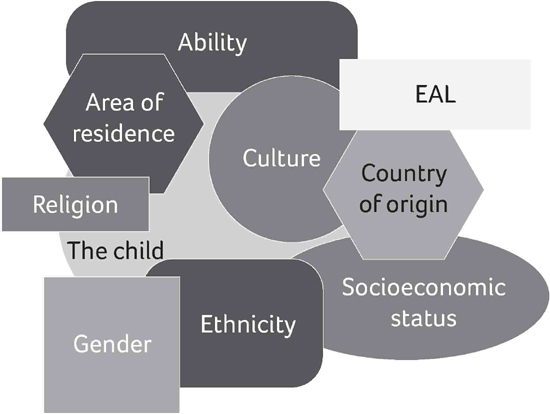

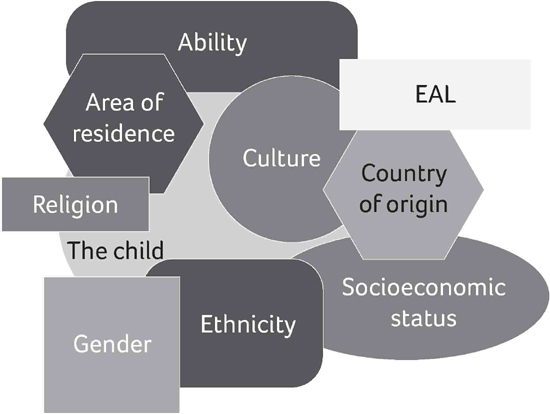

Diversity can be perceived to be in several layers. These layers can be visible or invisible due to overlap of categories or over-emphasis of certain categories.

highlights layers showing the categories the child belongs to and the influence of these categories on the child. The child can be covered by several categories of labels and experience discrimination. The categories overlap, which can result in the child being identified with a specific label(s) rather than seen as a holistic child. Some categories seem to rise above others in different contexts, especially home and school/early childhood settings. Some people might focus on certain categories and homogenise the needs of the child. Further categories can be added that are relevant to people and are considered important to identify themselves. Some categories will have greater relevance and significance for some groups of people (e.g. ability will be more obvious to teachers; gender will be significant to peers).

Figure I.1: Categories of labels attached to children

A child might be labelled as belonging to some of the above categories. Their perception relating to these categories might vary depending on the context of the setting. A child might relate to one or two categories that they identify with when comparing themselves to others. For example, Lauren, a three-year-old girl, might classify herself as a girl with curly hair. Other children might refer to Lauren as a kind and cheerful child. A parent might emphasise one or two other categories such as gender or ability, and that might be different to how a friend/peer or a practitioner/professional might highlight more visible categories relevant to learning and development. Once a child is labelled, stereotypes associated with that label can influence how the child is perceived.

CASE STUDY

CASE STUDY

A three-year-old girl, Maaya, has Down syndrome. She lives in London and attends a private nursery. Her parents are from Malaysia and Italy.

Maaya might identify herself as a girl who loves dance and music.

Peers might identify Maaya as a three-year-old girl who has curly hair, is funny and is their friend.

Practitioners and professionals might see her as a disabled child with Down syndrome (maybe because of noticeable characteristics), who speaks English as an additional language (EAL). How they see her may also depend on the professional they are discussing her with, such as the speech therapist, educational psychologist, special educational needs co-ordinator (SENCO) or general practitioner (GP).

Her parents might relate to most of the attributes of the child such as gender, ethnicity, culture, religious affiliation and EAL ability.

Most of these attributes are visible. Some of these attributes can be more visible than others. How visible they are also depends on the individuals perspectives influenced by their knowledge and understanding, experiences and exposure to diversity.

CASE STUDY

CASE STUDY