Contents

CHAPTER I .

CHAPTER II .

CHAPTER III .

CHAPTER IV .

CHAPTER V .

CHAPTER VI .

CHAPTER VII .

CHAPTER VIII .

CHAPTER IX .

CHAPTER X .

CHAPTER XI .

CHAPTER XII .

CHAPTER XIII .

CHAPTER XIV .

Acknowledgments

TO FIRST EDITION

An attempt to record the names of all of the people who contributed to the concept of this book takes me back many years. I first became aware of the importance of literature as an influence on childrearing practices after reading and relying on Benjamin Spocks remarkable book Baby and Child Care. Medical school and internships in hospital pediatrics had in no way prepared me for coping with the real mothers of normal, healthy children and their problems. Dr. Spocks book made practice seem possible and even exciting. His wisdom has continued to support me and my patients mothers for nearly twenty years.

My colleagues in the practice of pediatrics, Ralph A. Ross, M.D., and John S. Robey, M.D., have helped me keep my feet on the ground and have been a constant source of rewarding suggestions. Teachers such as Allan M. Butler, M.D., Charles A. Janeway, M.D., Milton Senn, M.D., and Stewart Clifford, M.D., opened doors with their substantial knowledge of pediatrics and its role in a larger picture. To such colleagues as Gertrude Reyersbach, M.D., William Cochran, M.D., Katherine Kiehl, M.D., and Elizabeth Gregory, M.D., I owe many of the wiser statements in this book.

An immersion in child psychiatry opened my eyes to the role of the mother in shaping her child, to the childs important strength in shaping his environment, and to the fathers role in maintaining a safe anchorage for them both. At the James Jackson Putnam Childrens Center, Marian C. Putnam, M.D. and Beata Rank provided a unique climate for learning about child development and for observing the effects of early intervention in the disturbed homes of small children. In this remarkable center, such mentors as Gregory Rochlin, M.D., Dorothy MacNaughton, M.D., Eveoleen Rexford, M.D., Eleanor Pavenstedt, M.D., Samuel Kaplan, M.D., Harriet S. Robey, Marta Abramowicz, and Irene Anderson taught me how to see the underlying mechanisms that produced behavior in mothers, fathers, and their children. Grace A. Young taught me how to look at behavior and see the rich language that it represented. Without her imagination and her ability to see the importance of each bit of behavior, I could never have learned how to recognize the many ways in which infants and their parents communicate long before speech takes its symbolic role.

In the area of research, Lucie Jessner, M.D., John Benjamin, M.D., Louis Sander, M.D., Bettye Caldwell, Ph.D., Sally Provence, M.D., Mary Louise Scholl, M.D., Sanford Gifford, M.D., and Margaret Bullowa, M.D. have provided opportunities for developing ideas central to this book. More recently, Professor Jerome S. Bruner in cognitive development and Professor Evon S. Vogt and George Collier in anthropology have opened for me new and exciting areas in infant research.

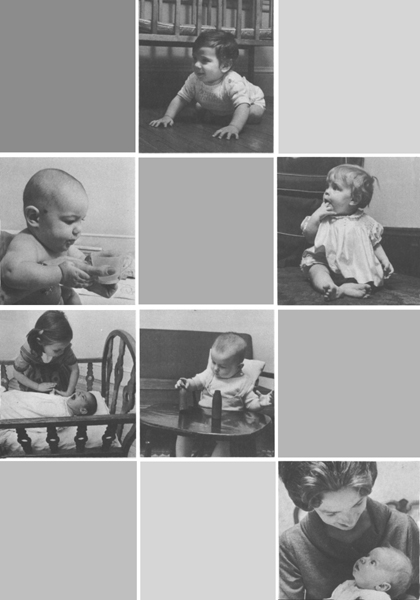

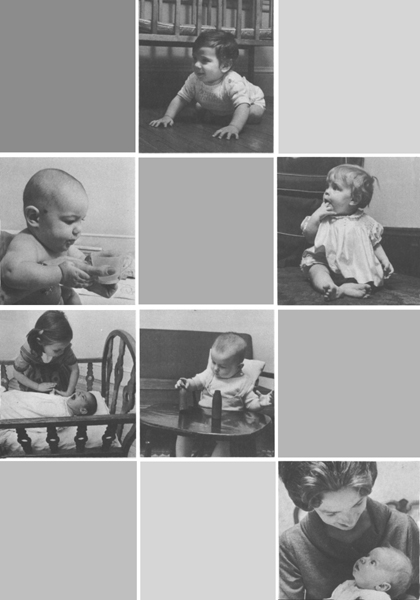

Deirdre Carr, editor of Baby Talk magazine, first urged me to conceptualize the three individual kinds of development that were possible in our culture. Stella Chess and Andrew Thomas had made it de rigueur to think of different styles of development in children after Margaret Friess remarkable paper in the early 1950s, which recorded the observable differences in newborn babies. Esther S. Yntema first thought a book could be written along these lines and spurred me to a start. Marian Poverman and Elizabeth Hoffman supported me through periods of self-questioning about the importance of such a book. My wife has acted as critic and editor throughout the ordeal of recording and sorting out its ideas. Merloyd Lawrence has been a source of creative ideas in its editing. Lew Merrim and Gary Schweizer-Tong, as well as several parents, have furnished its important visual dimension, the descriptive photographs. Those taken by Mr. Merrim appeared first in Baby Talk magazine.

But, most important of all, I must pay just homage to the many hundreds of mothers of patients who taught me all I know about child rearing. Their wisdom, their rewarding insights brought in to me on routine visits, their patience in enduring my often too-personal questions and my temperamental outbursts of frustration and/or fatigue have made the practice of pediatrics a rewarding way of life and have made the recording of all the experiences depicted in this book the frosting of such a way of life. Without this rich communication between doctor and patient, I can see that medical practice could become sterile and unrewarding on each side of the relationship. I hope this book may help to keep alive that personal interdependence of doctor and patient that is such a vital element in the practice of medicine.

Acknowledgments

TO REVISED EDITION

In order to capture the important role of fathers in the families of these babies, a number of fine photographs taken by Steven Trefonides have been added to this revision.

My daughter, Christina, has been of enormous importance in helping me clarify my thoughts about the changing pressures on young families. She helped me shape a new introduction and meticulously scoured the text for opportunities to include changes in the roles of fathers and working mothers, and in family styles. We found, as she and I worked, that the changes were so important and that there were so many implications for childrearing that they deserved an entire volume. Hence, instead of changing the focus of this book from its present oneon the individuality of the infantwe intend to write a new book on childrearing. This will be for single parents and for working mothers and fathers. I hope this present revision will meet some of their needs, and the future volume will speak to the concerns that weigh upon over half of young families today.

Over the past thirteen years, several of my associates in researchEdward Tronick, Heideliese Als, Kevin Nugent, Kenneth Kaye, Frances Horowitz, Myrtle McGraw, Leila Beckwith, Elizabeth Maury Fox, Michael Yogman, Suzanne Dixon, Constance Keefer, Robert and Sarah LeVine, Barbara Koslowski, and Mary Mainhave made lasting impressions on my thinking. I am deeply indebted to them all.

Foreword

TO FIRST EDITION

There is a zest and vitality in human infancy that shows itself at every turn. The infant looks with absorption, drinks in his environment well before he knows how to do anything about taking hold of it. He scouts his world for every sign of what is novel and monitors not only what goes on right before him but what is happening at the edges of his world. At the start, in the opening weeks of life, the baby is either alert, turned on, and in a mood to explore, or he is turned off in the total way that young infants have of turning off. Gradually, alertness spreads over longer periods and the infant begins on new taskssocial life, manipulation of things, and the gradual lacing together of the world of the eyes with the world of the hands. A career of self-projected travel begins earlyperhaps when the baby can turn from his back to his tummyand the realm over which control extends expands as no empire ever has.