Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the Print Version

Sara Guyer and Brian McGrath, series editors

Lit Z embraces models of criticism uncontained by conventional notions of history, periodicity, and culture, and committed to the work of reading. BoOks in the series may seem untimely, anachronistic, or out of touch with contemporary trends because they have arrived too early or too late. Lit Z creates a space for books that exceed and challenge the tendencies of our field and in doing so reflect on the concerns of literary studies here and abroad.

At least since Friedrich Schlegel, thinking that affirms literatures own untimeliness has been named romanticism. Recalling this history, Lit Z exemplifies the survival of romanticism as a mode of contemporary criticism, as well as forms of contemporary criticism that demonstrate the unfulfilled possibilities of romanticism. Whether or not they focus on the romantic period, books in this series epitomize romanticism as a way of thinking that compels another relation to the present. Lit Z is the first book series to take seriously this capacious sense of romanticism.

In 1977, Paul de Man and Geoffrey Hartman, two scholars of romanticism, team-taught a course called Literature Z that aimed to make an intervention into the fundamentals of literary study. Hartman and de Man invited students to read a series of increasingly difficult texts and through attention to language and rhetoric compelled them to encounter the bewildering variety of ways such texts could be read. The series conceptual resonances with that class register the importance of recollection, reinvention, and reading to contemporary criticism. Its books explore the creative potential of readings untimeliness and historys enigmatic force.

LOOK ROUND FOR POETRY

Untimely Romanticisms

Brian McGrath

Fordham University Press

New York2022

Fordham University Press gratefully acknowledges financial assistance and support provided for the publication of this book by Clemson University.

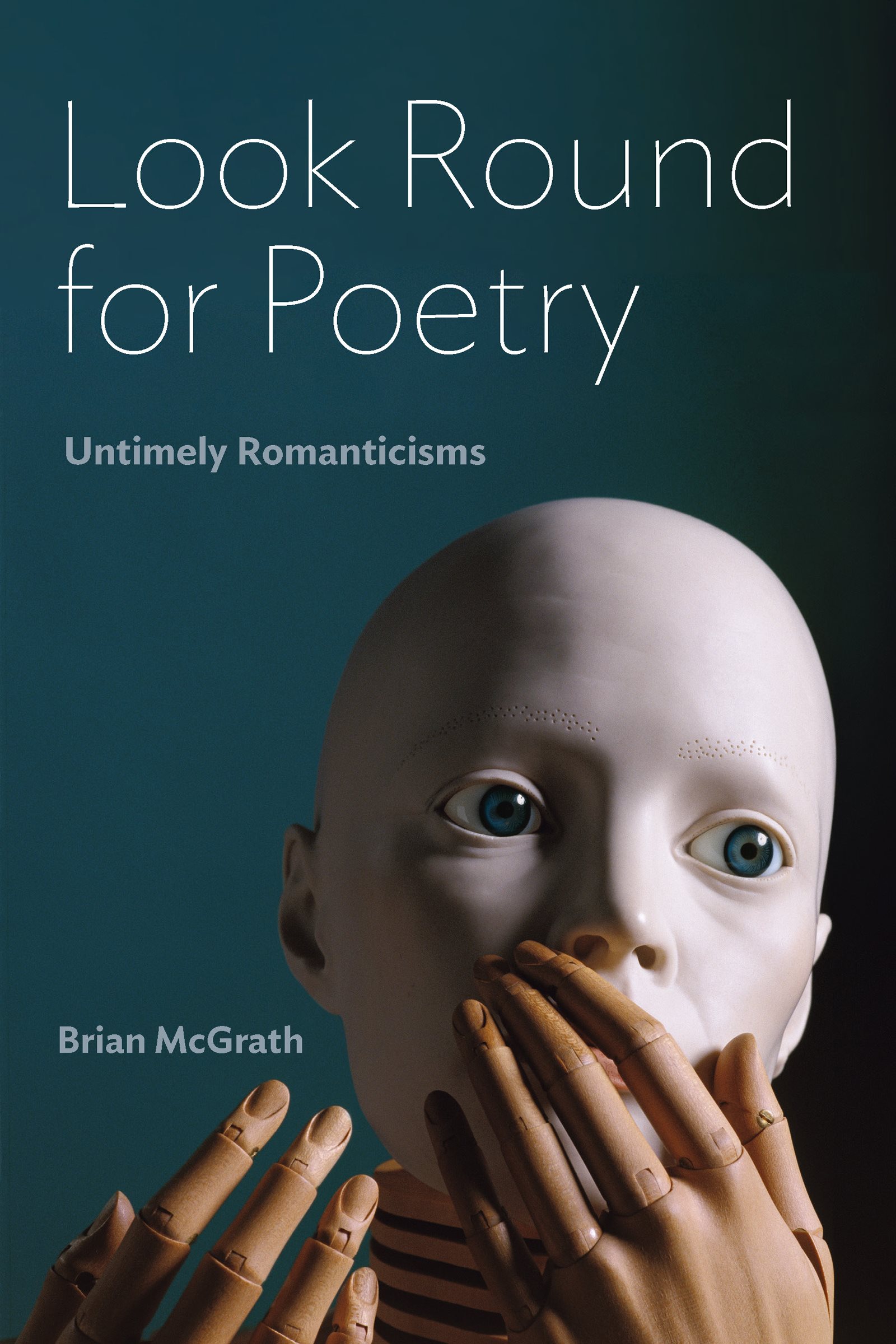

Cover art:

Elizabeth King, Animation Study: Pose 7, 2005, Chromogenic Print, 20 20 inches

Sculpture: Elizabeth King, Pupil, 198790; porcelain, glass eyes, carved wood, brass; half life-size, all joints movable; Collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden , Washington, D.C.

Pose and composition: Elizabeth King

Lighting and camera: Eric Beggs

Master printer: Lauren Kylie Wright

Copyright 2022 Fordham University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Visit us online at www.fordhampress.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available online at https://catalog.loc.gov.

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 225 4 3 2 1

First edition

Contents

Introduction

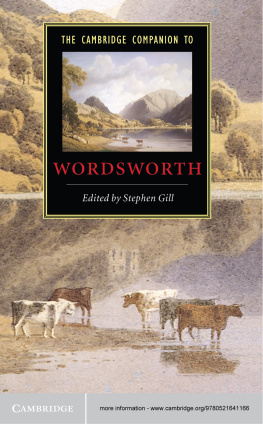

They will look round for poetry, and will be induced to enquire

William Wordsworth, advertisement to

Lyrical Ballads (1798)

The longer I linger with the grammatical and rhetorical structures that give a poem shape the more I feel I see these same structures around me. Linguists and psychologists have various terms for this experience (or condition), as selective attention leads to confirmation bias: when one learns something new or studies something for a while, one tends to see it more often and even all around one. The idea that one who studies poetry might see poetry all around may surprise few, but in Look Round for Poetry I take this experience as a charge. I place in apposition select poems and various tropes and figures common in economic, technological, and political discourse and celebrate poetrys capacity to make the rhetoric of contemporary life differently legible.

This book started to emerge as various social media platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter, became increasingly ubiquitous. At the time I was leading a Theory colloquium for students in a PhD program called Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design, during which we read a range of texts, from Aristotle to Wendy Hui Kyong Chun. The students were well prepared to think about rhetoric and interested in contemporary media and contemporary media theory. They were, generally speaking, less interested in poetry, but not because they disliked it. To many of them poetry just did not seem to fit the programs description. But the more we discussed the rhetoric of contemporary media, the more it felt, to me at least, like we were talking about poetry. As I only half-joked during one meeting, to me both Twitter and Facebook operationalize poetry for profit and so owe much to poetry. By happy chance, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) offers Geoffrey Chaucer, author of The Canterbury Tales, as the originator of the word twitter around 1380, used as a verb meaning to give a call consisting of repeated light tremulous sounds. Twitter owes at least its name to poetry. But extending this argument a little, one might say that Twitter realizes, or at least works to allow users to realize, a long-standing and relatively common poetic dream. To participate in Twitter, to tweet, is to imagine oneself a bird; and as many introductory poetry textbooks show, poets often write about birds, imagine themselves as birds, ask readers to imagine themselves as birds. The topic is an old one, but one put to dramatic purpose when one dominant form of human communication in the twenty-first century subtly (or not so subtly) blurs the line between human and nonhuman tweets. This argument was only almost persuasive in the colloquium, among students trained in the available arts of persuasion; so I tried another example. Facebooks name has a literal referent, a book of faces, but it also recalls a dominant poetic trope, prosopopoeia, by which a poet grants a face (and so the possibility of voice) to a nonhuman entity or inanimate object .When the poet-speaker is a corpse or a cloud, the poet gives voice and life to the voiceless and lifeless. And while this trope might appear only every so often and only in select poems, especially elegies, the rhetorical structure has been immensely important to the study of poetry, especially when authors of poetry textbooks discuss and celebrate the poets so-called voice. To learn to read a poem well is to learn to hear the poets voice. The poets voice lives in the poem. Readers are taught to grant the poem a face so that it might speak, so that they might hear it.

But these common rhetorical tropes that determine the study of poetry, of lyric, perhaps especially, also determine reading more generally. As Barbara Johnson explains in Persons and Things: poetry convinces the reader that the poet speaks, that the poem gives access to his living voiceeven though the individual author may have been buried for more than two hundred years. This is the immortality of literature brought about by readingto bring alive the voice of the dead author. A text speaks.