William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright Adam Nicolson 2019

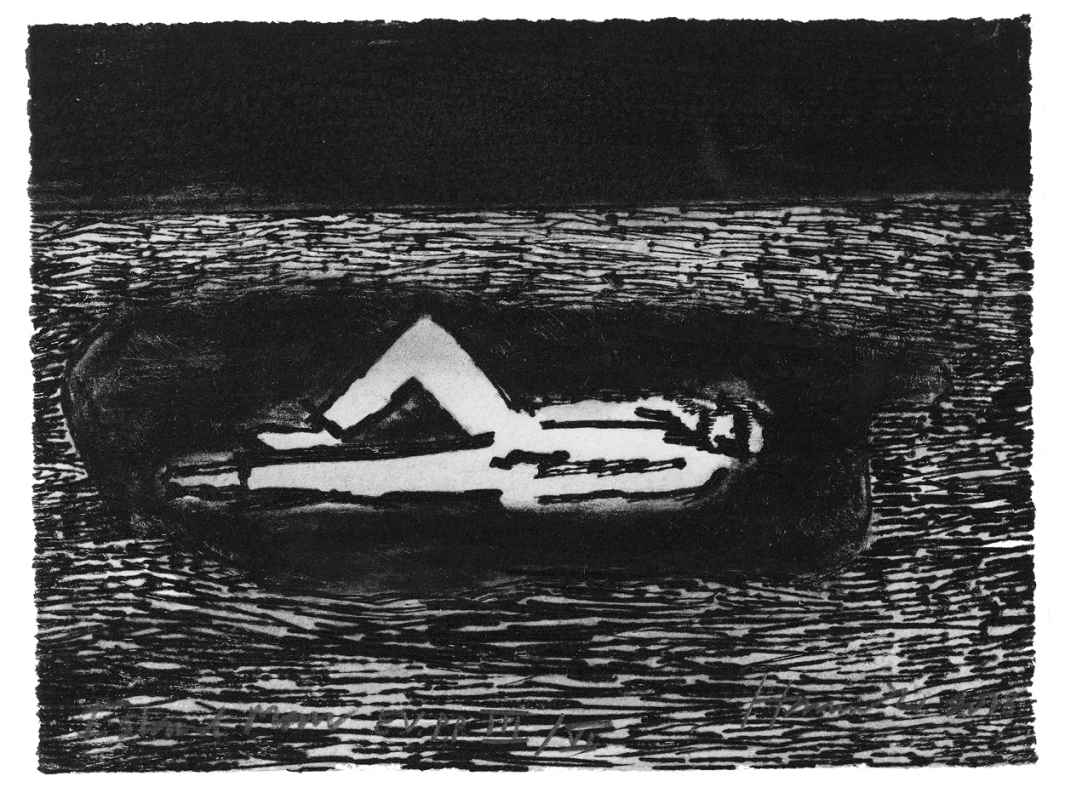

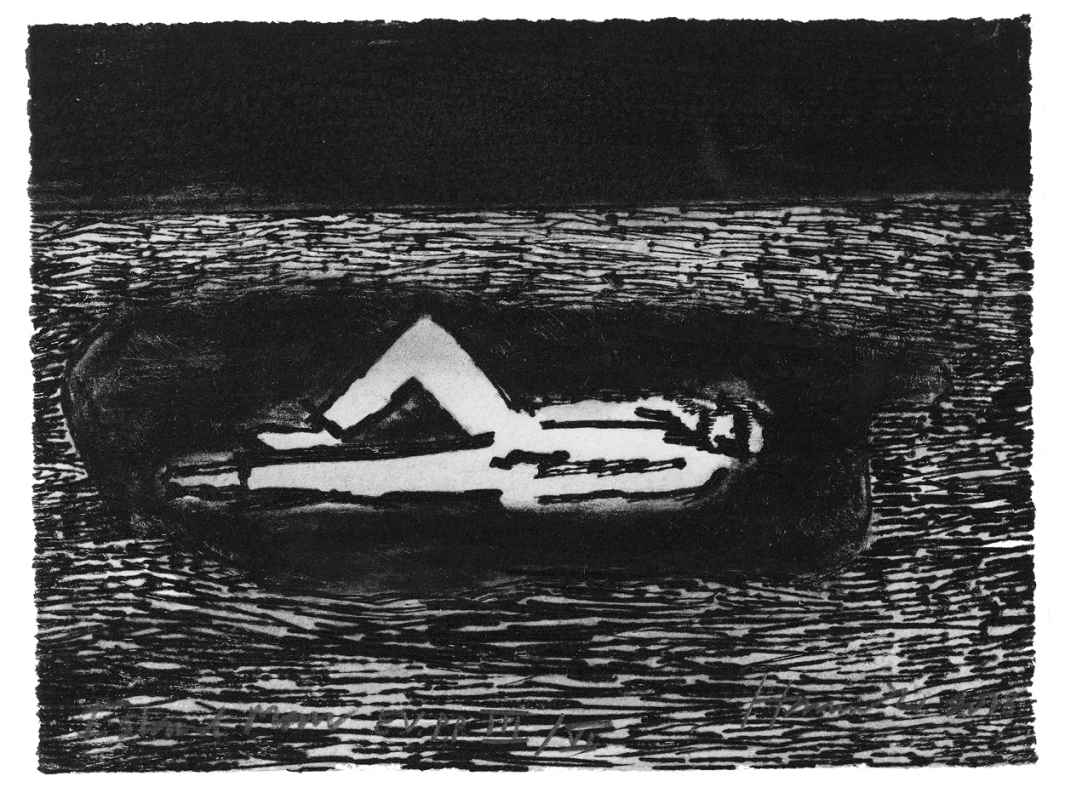

Cover image In Xanadu (Island Studio)

All woodcuts photographed by Leigh Simpson

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008126476

Ebook Edition June 2019 ISBN: 9780008126483

Version: 2019-05-20

For Tom Hammick

On the island of his self

The making of verses, the making of works, occurs in the edges of your life, of your time, in your late nights or early mornings And my words, the words for me, seem to have more nervous energy when they are touching territory that I know, that I live with I can lay my hand on [a place] and know it. And the words, the words come alive and get a kind of personality when they are involved with it for me. The landscape is image. Its almost an element to work with, as much as it is an object of admiration.

Seamus Heaney, speaking to Patrick Garland on Poets on Poetry, BBC 1, October 1973

Contents

1 Following

Acknowledgements

Also by Adam Nicolson

Landmarks

List of Pages

The year, or slightly more than a year, from June 1797 until the early autumn of 1798, has a claim to being the most famous moment in the history of English poetry. In the course of it, two young men of genius, living for a while on the edge of the Quantock Hills in Somerset, began to find their way towards a new understanding of the world, of nature and of themselves.

These months have always been portrayed by Wordsworth and Coleridge and by Wordsworths sister Dorothy as much as by anyone else as a time of unbridled delight and wellbeing, of overabundant creativity, with a singularity of conviction and purpose from which extraordinary poetry emerged.

Certainly, what they wrote adds up to an astonishing catalogue: This Lime Tree Bower My Prison, Kubla Khan, The Ancient Mariner, Christabel, Frost at Midnight, The Nightingale, all Wordsworths strange and troubling poems in Lyrical Ballads, The Idiot Boy, The Thorn, the grandeur and beauty of Tintern Abbey, and, in his notebooks, the first suggestions of what would become passages in ThePrelude.

The grip of this poetry is undeniable, but its origins are not in comfort or delight, or, at least until Wordsworths walk up the Wye valley in July 1798, any sense of arrival. The psychic motor of the year is something of the opposite: a time of adventure and perplexity, of Wordsworth and Coleridge both ricocheting away from the revolutionary politics of the 1790s in which both had been involved and both to different degrees disappointed. Wordsworth was unheard of, and Coleridge was still under attack in the conservative press. Both were in retreat: from cities; from politics; from gentlemanliness and propriety; from the expected; towards nature; and in a way that makes this year foundational for modernity towards the self, its roots, its forms of self-understanding, its fantasies, longings, dreads and ideals. For both, the Quantocks were a refuge-cum-laboratory, one in which every suggestion of an arrival was to be seen merely as a stepping stone.

The path was far from certain. One of Wordsworths criteria for pleasure in poetry was the sense of difficulty overcome, and that is a central theme of this year: their poetry was not a culmination or a summation, but had its life at the beginning of things, at a time of what Seamus Heaney called historical crisis and personal dismay, emergent, unsummoned, encountered in the midst of difficulty, arriving as unexpectedly as a figure on a night road, or a vision in mid-ocean, or the wisdom and understanding of a child.

It was not about powerful feelings recollected in tranquillity. Wordsworths famous and oracular definition would not come to him until more than two years after he had left Somerset. This was different, a poetry of approaches, journeys out and journeys in, leading to the gates of understanding but not yet over the threshold. Even now, 250 years after Wordsworths birth, it still carries a sense of discovery, drawing its vitality from awkwardness and discomfort, from a lack of definition and from the power that emanates from what is still only half-there.

This book explores the sources of this effusion. I wish to keep my Reader in the company of flesh and blood, Wordsworth would write a couple of years later, and that has been my guiding principle too. The place in which these poets lived, the people they were, the people they were with, the lives they led, the conversations they had: how did all of that shape the words they wrote?

The received idea of these poets puts its focus on the immaterial, the floatingly high-minded. But here, in 1797, that is at least partly the opposite of the case. Thought for them, as the young Coleridge had written in excitement to his friend Robert Southey, was corporeal. He would later coin both neuropathology and psychosomatic as terms to describe aspects of this new interpresence of body and mind. The full life was not the enjoyment of a view, nor any kind of elegant gazing at a landscape, let alone sitting reading, but a kind of embodiment, plunging in, a full absorption in the encompassing world, providing the verbal life and nervous energy that came from what Heaney would call touching territory that I know.

Here, then, was the invitation to which this book is an answer. If this was one of the great moments of poetic consciousness, it could best be understood as physical experience. By feeling it on the skin I could hope to know what had happened in the course of it. This was the subject that drew me: poetry-in-life, poetry-in-place, the body in the world as the instrument through which poetry comes into being.

The implication of that idea is that all currents must flow together. The way to approach this moment, its involutions and complexities, was to do, as far as possible, what the poets had done, to be in the Quantocks in all the moods and variations of the year at its different moments, to look for what happened and what emerged from what happened, to see how they were with each other, to feel the ebb and flow of their power relations and their affections. The timings and geography are closely known, often day by day, almost always week by week: what they were discussing, who they were meeting, how they were behaving, who their enemies and friends were, how poetry came from life-in-place.

Richard Holmes, the biographer of Shelley and Coleridge, has, unknown to him, long been my guide. When I was a young writer in the early 1980s he sent me a postcard out of the blue, encouraging me to keep going. So I have, and I think of this book as a tributary to the great Holmesian stream. Its method is his: to follow in the footsteps of the great, looking to gather the fragments they left on the path, much as Dorothy Wordsworth was seen by an old man as she was accompanying her brother on a walk in the Lake District, keeping close behint him, and she picked up the bits as he let em fall, and tak em down, and put em on paper for him.