Contents

List of Figures

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

for Kate Boxer

Heraclitus on the shore.

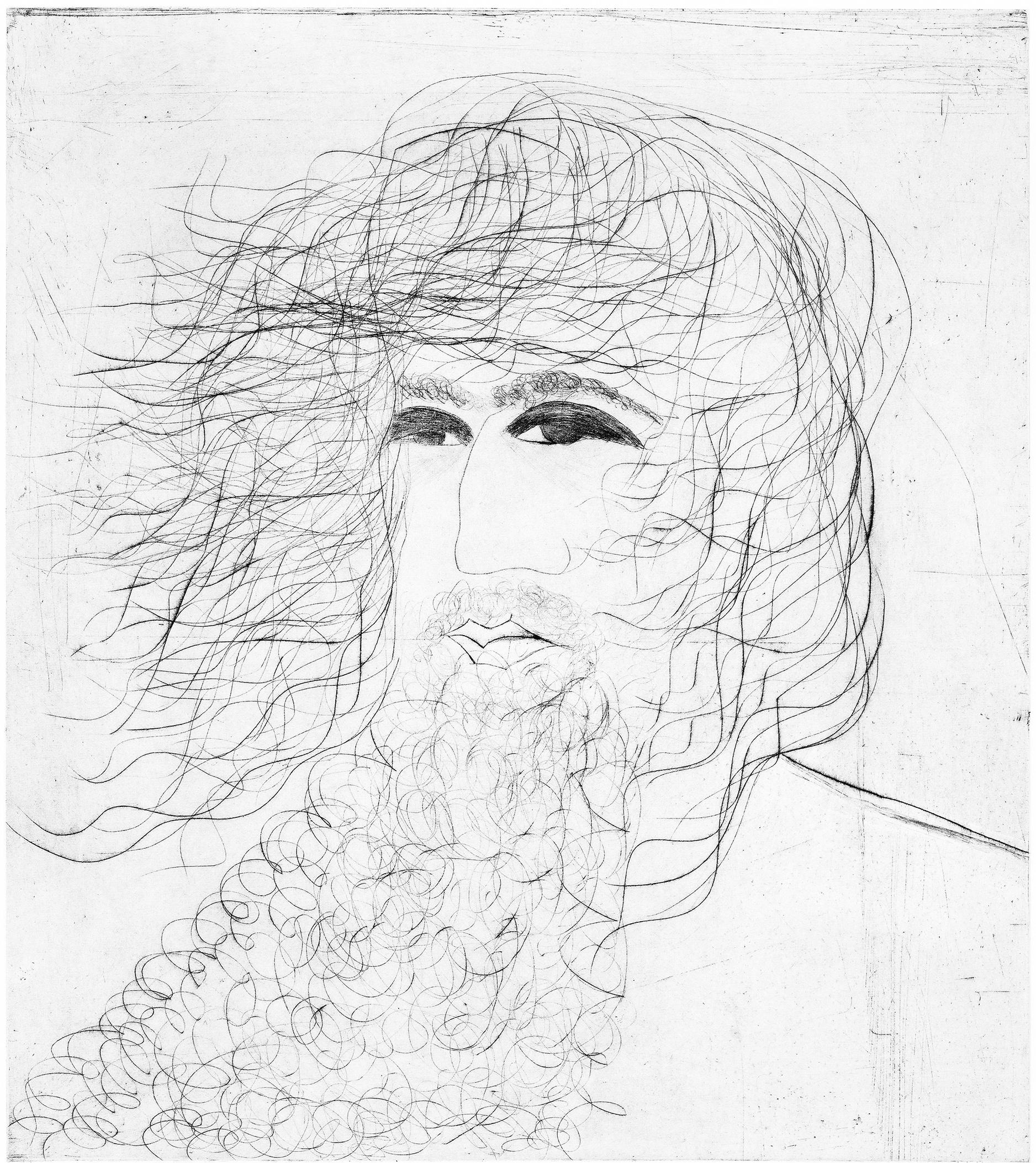

Picture sections: all photography authors own and all illustrations courtesy of Kate Boxer.

Sources of in-text photographs and illustrations not by AN or Kate Boxer

Eliza Dorville drawings of amphipods: from George Montagu F. L. S., Testacea Britannica, Supplement, London 1808, online at https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/

Pardi on the beach: from Guido Caniglia, Understanding Societies from Inside the Organisms. Leo Pardis Work on Social Dominance in Polistes Wasps (19371952), Journal of the History of Biology, Vol. 48, No. 3, Harvard Fatigue Laboratory (Fall 2015), pp. 45586, 461.

Thompson zoeae: from J. V. Thompson, Zoological Researches, 1828, 1, 3.

Thompson portrait: J. V. Thompson painted by M. D. Roux, Port Macquarie Museum, New South Wales.

T. S. Eliot on the porch of his familys summer house, on Cape Ann, Massachusetts, in 1896. Photograph by Henry Ware Eliot, Jr./Houghton Library, Harvard University modern ms am 2560 163.

Anthopleura elegantissima: from https://coldwaterdiver.net/cold-sub-aqua-photographs/dscn4340/

John Raven: from Raven family collection.

Bob Paine: from http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/paine-robert.pdf

AN sailing: photograph by James Nutt.

Descartes: from Ren Descartes, Principia philosophiae (1644), p. 84.

Newton: from https://qstbb.pa.msu.edu/ed/lectures/L9_Cosmology_Two_2/

Roy map extract: The British Library Board Roy Map Strip 11, Section 6c. Shelfmark: British Library Maps CC.5.a.441 11/6c.

Clachan: A Highland Clachan Loch Duich, Ross-shire, 2883 G.WW, Photograph Album No. 33: Courtauld Album Canmore National Record of the Historic Environment Courtesy of Historic Environment Scotland (George Washington Wilson).

Preacher: a minister of the Free Church of Scotland preaching the Gospel in the 1840s before the erection of its first church buildings, Rev. Thomas Brown, Annals of The Disruption, Vol. 1, Edinburgh 1877.

Spencer: Herbert Spencer. Photograph, 1889. Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Sources for Rosie Nicolsons figures and maps

All from sketches by AN except:

Fossat: adapted from Pascal Fossat et al., Measuring Anxiety-like Behavior in Crayfish by Using a Sub Aquatic Dark-light Plus Maze, bio-protocol.org/e1396 Vol. 5, Iss. 3 (5 January 2015).

Winkle: adapted from photographs in Robin Hadlock Seeley, Intense Natural Selection Caused a Rapid Morphological Transition in a Living Marine Snail, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Vol. 83, No. 18 (15 September 1986), 6897901.

Crab distribution: adapted from James T. Carlton and Andrew N. Cohen, Episodic Global Dispersal in Shallow Water Marine Organisms: The Case History of the European Shore Crabs Carcinus maenas and C. aestuarii, Journal of Biogeography, Vol. 30, No. 12 (December 2003), 180920.

Crab holding drawings: adapted from photographs in Michael Berrill and Michael Arsenault, Mating Behavior of the Green Shore Crab Carcinus maenas, Bulletin of Marine Science 32(2) (1982), 6328.

Crab headland: adapted from sketch map in Gro I. Van Der Meeren, Sex- and Size-Dependent Mating Tactics in a Natural Population of Shore Crabs Carcinus maenas, Journal of Animal Ecology, Vol. 63, No. 2 (April 1994), 30714.

UK tide: adapted from Sankaran, Abhinaya et al., Variability and Phasing of Tidal Current Energy around the United Kingdom, Renewable Energy 51 (2013) 34357.

Tidal squeeze: hydrography adapted from Admiralty Chart 2171: Sound of Mull and Approaches, UK Hydrographic Office.

Fairy map of Morvern: base map and contours adapted from Explorer 383 1:25,000, Morvern & Lochaline, Kingairloch, Ordnance Survey 2015.

Zigzag wrack graph: adapted from Stephen J. Hawkins et al., From the Torrey Canyon to Today: A 50-Year Retrospective of Recovery from the Oil Spill and Interaction with Climate-Driven Fluctuations on Cornish Rocky Shores, Abstract #138 for 2017 International Oil Spill Conference.

Exposure diagram: adapted from David Raffaelli and Stephen Hawkins, Intertidal Ecology (Chapman & Hall, 1996), p. 95.

Sound of Mull, summer 2020.

The sea is not made of water. Creatures are its genes. Look down as you crouch over the shallows and you will find a periwinkle or a prawn, a claw-displaying crab or a cluster of anemones ready to meet you. No need for binoculars or special stalking skills: go to the rocks and the living will say hello.

In the 1850s, when Victorian Britain fell in love with the seaside, the rock pool became the heart of a kind of nature- worship which saw in its riches and calm a reassuring vision of creation. Life in what Philip Henry Gosse, the great apostle of the pools, called these unruffled wells was a gathering of goodness and even happiness. It was as if the pools came from a time before the Fall, when life was innocent and unthreatened. Gosse, surely half-remembering the childrens rhyme, imagined Adam and Eve, stepping lightly down to bathe in the rainbow-coloured spray. At just the moment Darwin was challenging the God-ordained vision of nature, and setting the whole of life adrift on chance-driven change, the rock pools looked to those Victorians like gardens of prelapsarian bliss, glimmering enclosures in which nature seemed to have enshrined perfection and permanence.

We have inherited some of that Victorian longing for calm. We still go to the seaside for consolation and simplicity. Demands and anxieties seem to drop away there; things still are as they were when we were ten. The rock pools still beckon, the blennies and gobies still shimmer beneath us. But there are ironies in choosing the shore as a theatre for reassurance. Even if its changes are dependable and rhythmic, it is thick with variability. A tidal coast is filled with that paradoxical quality: reliable unreliability, both closed and open-ended, both familiar and strange. Regularity toys with uncertainty there. Nothing is more predictable than the coming and going of the tide and yet nothing about it can be relied on: daily revelation and daily erasure, daily loss and daily reacquisition.

This book is about those multiple layers between the tides, the ways in which the simple overlies the less-than-simple there, the extraordinary mirroring of human and animal life on its shores, in pools that are silent and beautiful and as full of threat as any rats alley or Roman circus. The intertidal is rich but troubled; as no coincidence, it is one of the most revelatory habitats on earth. Of all the great discoveries made in the science of nature, from a grasp of taxonomy, to the sequence of creatures through time revealed in the rocks, the adaptations of organisms to circumstance, the idea of natural selection finally crystallising in Darwins mind as he spent eight long years examining the inner structures of the barnacle the working of ecological webs and the governing importance of trophic cascades all these ways of understanding the pattern of life first emerged from studying what was happening to animals and plants between the tides.