insight text guide

Sue Tweg

Medea

Euripides

Copyright Insight Publications

First published in 1999, based on the translation by Philip Vellacott. Reprinted with corrections in 2009.

Revised and reprinted in 2014 with text revisions based on the translation by John Davie. Reprinted in 2015, 2016, 2017.

Insight Publications Pty Ltd

3/350 Charman Road

Cheltenham VIC 3192

Australia

Tel: +61 3 8571 4950

Fax: +61 3 8571 0257

Email:

www.insightpublications.com.au

Copying for educational purposes

The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10% of this book, whichever is the greater, to be copied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or the body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency under the Act.

For details of the Copyright Agency licence for educational institutions contact:

Copyright Agency

Level 11, 66 Goulburn Street

Sydney NSW 2000

Tel: +61 2 9394 7600

Fax: +61 2 9394 7601

Email:

Copying for other purposes

Except as permitted under the Act (for example, any fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review) no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All inquiries should be made to the publisher at the address above.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Tweg, Sue.

Insight text guide: Euripides Medea.

Bibliography

9781875882274

1. Euripides, 480406 BC Medea. 2. Euripides, 480406 BC Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. (Series: Insight text guide)

Other ISBNs:

9781925175677 (digital)

9781925175684 (bundle: print + digital)

Cover design: The Modern Art Production Group

Printed in Australia.

contents

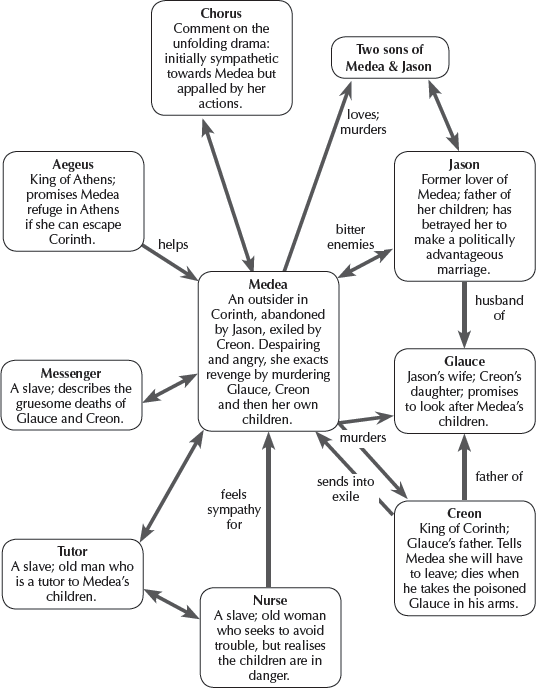

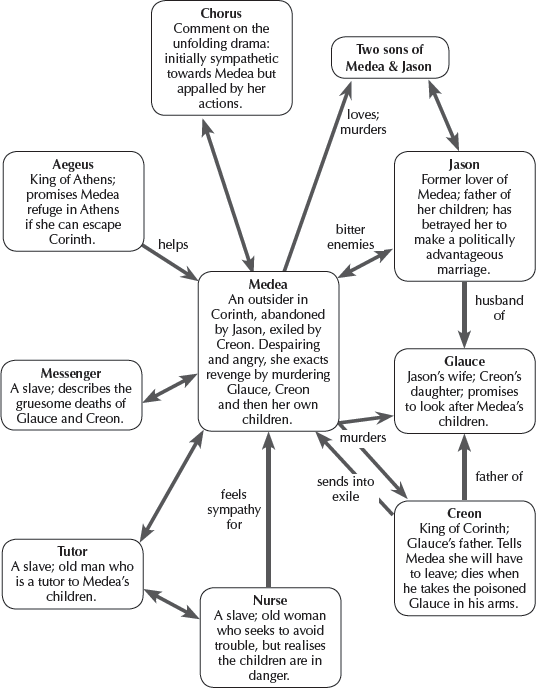

CHARACTER MAP

INTRODUCTION

Medea was first performed over two thousand years ago. Its one of a very select group of plays thirty-one in all (with several hundred others lost) that still speak across the centuries from fifth century BC Greece. Nineteen of all the plays that remain are by Euripides. Euripides version of Medea was the first, and is the only surviving, play out of seven on the same subject by other writers.

The underlying theme of this play is deadly conflict, somehow appropriate since Medea was first performed in 431 BC, the year hostilities broke out between the rival city states of Athens and Sparta. This was the beginning of the Peloponnesian War that would drag on for the rest of Euripides life. He died about three years before peace was concluded, with the defeat of Athens in 404 BC. Little is known about his life, although there is one poignant connection with the subject matter of Medea: for some reason, when he was over seventy, Euripides left Athens for voluntary self-exile in Macedonia, where he wrote his last great play The Bacchae.

Throughout its long performance history, Medea has moved audiences to pity and terror, the supreme tragic emotions according to Aristotle. Medea herself is one of the great roles for an actor, demanding psychological strength, intense emotion and nuance.

During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, Medeas cruelty in killing her children became a main focus of interest. Shakespeare connected Jason and Medea as tragic lovers in The Merchant of Venice, also identifying her as a sorceress, which was a favourite way of representing her in Pre-Raphaelite art. With her magic cauldron, she becomes the beautiful, cunning witch, sexually alluring but deadly.

Medea did not win the first prize for Euripides in the 431 BC festival, probably because it spoke out too plainly to Athenian citizens about mens relationships with women, passion set against reason, and a civilised citys rough treatment of aliens. The play also criticised a popular hero, and contained an ambiguous characterisation, bordering on the disrespectful, of Aegeus, the wily but sterile old king of Athens. Euripides was never a popular playwright in Athens: Medea, his first real tragedy, gives us some idea why.

BACKGROUND & CONTEXT

Greece in Euripides time

Ancient Greece, and Athens especially under the rule of Pericles from the mid-fifth century BC, is still popularly thought of as the home of democracy and the model of civilised life, a place where philosophers like Socrates and Plato could think and teach, where sciences and the arts could flourish. This romantic view of Athens as the ideal of civilised community life was absorbed into Roman culture, later filtered through the Middle Ages into Renaissance Europe and thence, through literature, mythology and art, into our world, which is where we begin to study Medea. If Athenian life in reality was less than glorious, we get hints about it through the work of Euripides.

Athenian democracy and citizenship

Medea is Athenocentric, conscious that it is playing to a crowd largely made up of Athenian citizens, who identify with every reference to their democratic state. At the heart of Greek tragedy as an art form is a concern about Athens and what it stands for: explicit criticism is rare, although, as well see in Medea, citizens at a play were often challenged to think about ingrained attitudes and assumptions.

Euripides, a citizen of democratic Athens, had certain rights and responsibilities. Since early in the fifth century BC, Attica, a geographical unit of ten tribes under the control of the most powerful city, Athens, was subdivided into townships or suburbs called demes. This is the origin of the word democracy: all citizens, rich and poor, were expected to play a part in the maintenance of their state and to demonstrate interest in what was going on through public debate of matters concerning Attica.

Of course, not everyone qualified to be a citizen, which is why it is praised in drama as something special, to be valued as a privilege. The greatest disaster that could befall a citizen was the loss of that identity. Medea is all about the trauma of exile and lost identity which Athens steps in to restore. One of the Choric odes specifically focuses on Athens as the epitome of harmonious civil life, blessed by the gods. In another play, by Sophocles, a character in exile declares that being without a polis (city) is equivalent to being dead.

Aristotle, writing a century after Euripides, defined a citizen as male, adult, freeborn, legitimate, of citizen descent on both the mothers and fathers sides, and with an active share in public decision-taking and office-holding. In Euripides time this meant about thirty thousand adult men in Athens, all of whom were expected to take some interest in state religious festival activities.

Theatre as a public educator

Greek dramatic spectacles were more than entertainment. They were acts of religion, involving the population as an ongoing public duty. Tragic theatre characteristically both confirmed and questioned Athenian democracy because it was political theatre, staged for and by the polis of Athens. One of the aims of Greek tragedy was to educate citizens in the practice of good citizenship: Look, this is how we do things; Listen, this is how to argue and make a debate. The ideal to be achieved in personal life was moderation, Nothing in excess. Plays like

Next page