Table of Contents

L. FRANK BAUM

Acknowledgments

The editors wish to thank the following persons: Frank J. Baum, son of L. Frank Baum, for supplying numerous details about his fathers life; Roland Baughman, head of the special collections department, Columbia University Libraries, for additions to the bibliography and for his great generosity in loaning a copy of the first edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz for the reproduction of certain of the original Denslow illustrations for this book; Anthony Boucher, editor of Fantasy and Science Fiction, for permission to reprint a heavily revised and expanded version of The Royal Historian of Oz, which first appeared in the January and February 1955 issues of his magazine; C. Beecher Hogan, lecturer in English at Yale University, for aid in the preparation of the bibliography; Fred Meyer, of Kinderhook, Illinois, for many valuable suggestions; and the late Jack Snow for providing the frontispiece photograph, the poster reproduced on the jacket, and much information about Baums life and writings.

Introduction

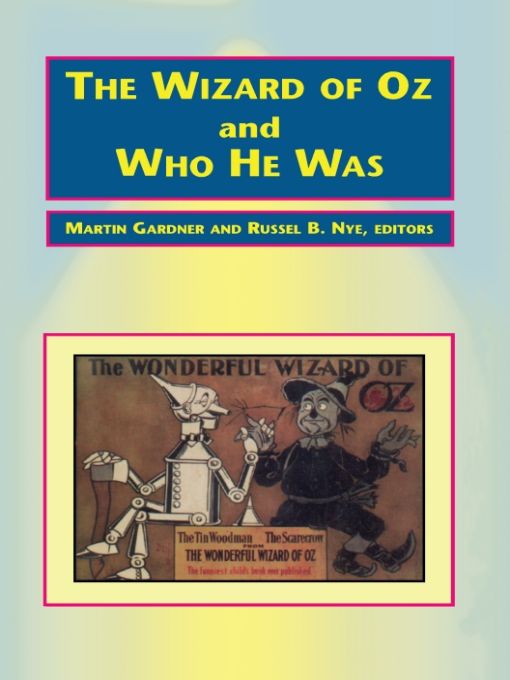

In 1957 popular culture was not yet an acceptable academic discipline : a Pulitzer prize-winning scholar would, in those days, have been expected to concern himself with weightier matters. Russel Nye, however, was a different kind of scholar, a scholar whose Jeffersonian political ideals extended beyond politics into a popular culture that others were denouncing as middlebrow. When Nye teamed up with Martin Gardner to bring out a new edition of L. Frank Baums childrens classic The Wizard of Oz and Who He Was the politics of culture came briefly into focus.

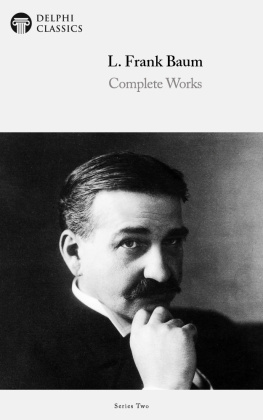

Martin Gardner in his introduction to the new edition addressed the question of who he was with a brief biographical essay on Baum. Lyman Frank Baum, we learn from Gardner, was born in 1856 near Syracuse, New York. He began his writing career in 1875 by founding the New Era, a newspaper still published in Bradford, Pennsylvania. He went on to manage opera houses, act in the theater, and establish a magazine for window dressers. In 1900 he wrote the first of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz books. Its popularity kept him writing Oz books for the rest of his life: and even beyond his life, for after he died in 1919 others were commissioned to write more books about the Wizard. Clearly, Baum was an American original, a gifted writer and a flamboyant promoter. In 1905 he purchased Pedloe Island off the coast of California and announced plans to build a miniature land of Oz for children. What might have been Americas first theme park was never built, but Baums Oz film company founded in 1914 did produce some silent screen versions of his tales. The 1939 film, starring Judy Garland, Ray Bolger, and Bert Lahr, was, in fact, the third film presentation of Oz.

Russel Nyes contribution to the new edition, aptly titled an appreciation, was a masterful combination of enthusiasm and scholarship, an overview of the world Baum created in fifteen admittedly uneven stories. Nye heard the echoes of Ben Franklin in Baums voice and noted specifically American virtues blended with European fairy-tale tradition. Nyes praise of Baum was tempered, however, by restraint and precision: he fairly acknowledged Baums limitations, as well as his gifts. Baums most unique gift, his uncanny understanding of children, explains, Nye noted, his failure to achieve critical or official popularity among the professional arbiters of childrens literature. The absence of overt moralizing provided parents with little help in adjusting and civilizing the young.

The writers understanding of children is one that the scholar seems to have shared. Commenting on Baums subtle and gentle humor, for example, Nye confidently predicted that children would enjoy the humor if adults can be prevented from explaining the joke. It should be noted, then, that Nyes appreciation of Baum is, most refreshingly, an appreciation of children, their needs, their joys, and, above all, their intelligence.

The urge to adjust and civilize was, it turned out, as compelling in 1957 as it had been years before when The Wonderful Wizard of Oz first appeared. When the Michigan State University Press published Nye and Gardners new edition with the original illustrations of W. W. Denslow no one expected that this childrens book would become a battlefield of clashing viewpoints.

The director of the Detroit Library, one Ralph Ulveling, triggered the battle when he attended a librarians conference at Kellogg Center. It had long been rumored that the Detroit library had been censoring books and Ulveling in his remarks about the Wizard seemed to confirm the rumors. Addressing the conference on April 3, 1957, or, as he later claimed, responding to a reporters question about The Wizard of Oz, Ulveling criticized the books for their negativism. Instead of setting a high goal, he continued, it drags young minds down to a cowardly level. The Oz books, he added, were old-fashioned and inferior to the modern books we stock. Although he acknowledged that there had been some demand for the book after the 1939 movie, he assured his audience that kids dont complain.

Ulvelings anti-Oz comments might have gone unnoticed if the Lansing State Journals staff reporter Neil Hunter hadnt featured his remarks under the headline Librarian raps Oz books. Aroused by the ugly odor of censorship, Lyle Blair, the director of Michigan State Universitys press, and Professor Nye responded rapidly with a press conference to defend the childrens classic. Blair defended the book as a great American literary work, and Nye remarked that, If the message of the Oz booksthat love, kindness and unselfishness make the world a better place was, as Ulveling said, of no value today, we should reassess a good many other things about our modern society besides the Detroit Librarys approved list of childrens books.

The United Press wires sent the story across the nation and Americas leading literary newspapers and magazines leapt to the defense of the Wizard. On April 28, 1957, the Boston Heralds commentator, the noted historian of the novel, Edward Wagenknecht, hoped that the books success would encourage Nye and Gardner to write a complete biography of Baum. The Washington Post picked up the story on the same day and, after giving Ulveling some lumps, predicted that Nyes prestige would rescue the Wizard from his enemies. Even conservative publications like the Wall Street Journal and William F. Buckleys National Review defended the Wizard. On May 1 the Wall Street Journal, quoting Martin Gardner, declared that Baum was Americas greatest writer of childrens stories, as everyone knows except librarians and writers of juvenile literature. On May 25, the anonymous editorialist of the National Review, displaying a Buckleyesque waggishness, issued a playful warning and threatened to turn Mr. Ulveling into an ass. The writer added that the citizens of Detroit having a deficient imagination will probably look at Mr. Ulveling and fail to see the change.

While the National Review threatened to change Mr. Ulveling into an ass, Anthony Boucher, writing in the August issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Fiction, tried to turn him into a verb. Ulvel, as Boucher defined it, was to homogenize; to render tasteless; to reduce to an indistinguishable and insipid mass; to apply such a process particularly to literature. Ulvel never caught on as a verb and Ralph Ulveling failed to achieve the infamy of William Bowlder, the nineteenth century purifier of texts, but he was provoked into launching a counter-attack in The American Library Bulletin. The whole alleged controversy, Ulveling charged, had all the ingredients of a publicity hoax. His librarys policy was to let copies of the Oz books wear out without replacing them. This is not banning, he insisted, it is selection.

Next page