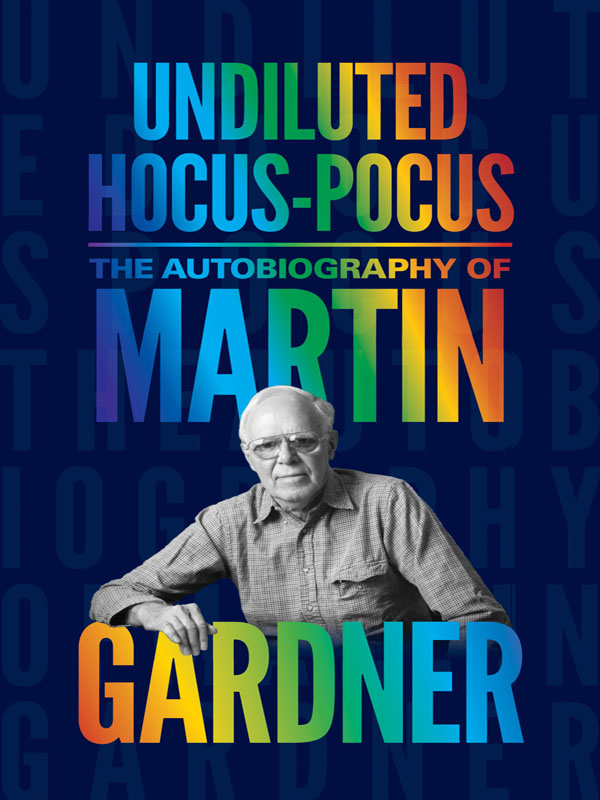

UNDILUTED HOCUS - POCUS

UNDILUTED HOCUS - POCUS

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF MARTIN GARDNER

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2013 by James Gardner as Managing General Partner,

Martin Gardner Literary Interests, GP

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

epigraph from Chicago, by Carl Sandburg, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

epigraph Woody Allen.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gardner, Martin, 1914-2010.

Undiluted hocus-pocus : the autobiography of Martin Gardner.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15991-1 (hardcover : acid-free paper) 1. Gardner, Martin, 1914-2010. 2. Science writersUnited StatesBiography. 3. Mathematical recreationsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 4. MathematicsSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 5. ScienceSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 6. JournalistsUnited StatesBiography. 7. MagiciansUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

QA29.G268A3 2013

793.74092dc23

[B]

2013016324

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Baskerville

10 Pro and League Gothic

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Jim and Amy,

ONE MORE TIME

We glibly talk of natures laws

but do things have a natural cause?

Black earth turned into yellow crocus

is undiluted hocus-pocus.

Piet Hein

CONTENTS

FOREWORD: MAGIC, MATHEMATICS, AND MYSTERIANS

LIKE THE HERO OF HIS CELEBRATED SHORT STORY, THE no-sided professor, Martin Gardner was an insider and an outsider at the same time. I first met him in the late 1950s at New Yorks 42nd Street Cafeteria. A magicians hangout on Saturday afternoons when the magic shops closed, it was a place where kids, serious amateurs, and professional magicians would traipse downstairs for coffee and whats new. There was always something new: a sheet of rubber you could pass a coin through, a down-on-his-luck gambler who had spotted the boys (there were hardly any girls) handling cards and stepped inside for a handout in exchange for showing them something they hadnt seen before. A typical Saturday had about fifty people scattered around five or more big circular tables. The youngsters (I was thirteen then) sat together. There was a fifteen-to-twenty-five age group and the big guys table. There were greats like Dai Vernon, Francis Carlyle, and Harry Lorayne, and various visiting pros and savants held court.

Martin was welcome at the big guys table. He was only ever a serious amateur magician, but he had invented some wonderful original tricks. Perhaps his best was lie speller, in which a spectator spelled out the name of a thought-of card, dealing one card off for each letter (j-a-c-k-o-f-c-l-u-b-s); at the end, the true thought-of card showed up even if the spectator lied along the way. Martin cataloged, compiled, and described The Encyclopedia of Impromptu Magic, which ran monthly in the beloved Hugards Magical Monthly. With hundreds of additions, a hardbound edition appeared a few years before his death.

Martin could perform a few obscure, difficult tricks really well. One was the invisible cigarette: a match is lit and the performer pretends to light an invisible cigarette; he mimes taking a puff and blows out a large cloud of real smoke. Another was a vanishing knot: a cleanly tied single knot in a handkerchief fades to nothing when pulled tight. He did a classical trick with two paper matches. Held interlinked at the fingertips, the matches just melted through one another. Martin had a high, quiet whisper of a voice. Frank Garcia, a top sleight-of-hand guy back then, would parody Martin whispering, Come closer; heres a trick with three human hairs. The diligent reader can find descriptions in Martin Gardner Presents.

By this time, Martin had started his epic Mathematical Games column in Scientific American. Often, tricks, puzzles, and games picked up at the cafeteria made their way into Martins columns. You might think that the magicians code of secrecy would have him banned, but the brethren loved having their discoveries read by an audience of close to a million readers. He was a center of attention both as a scholar and as a judge of what was new and worthwhile.

Martin was a quiet, nice guy, polite and enthusiastic, even to thirteen-year-olds. He was interested in everything: tricks, jokes (both black and blue), poems, psychology, and the philosophy of magic. Tricks with a scientific or mathematical background really tickled him, like the following. Find a single playing card. Make slight downward bends in two opposite corners. Hold it lightly from above by one hand, the thumb at one corner, pinky at the opposite. With no apparent effort, the card will slowly rotate until it is faceup. There is no trick to this, just a light touch. I was shown it in Toronto by Tom Ransom (himself an amazing magician and great puzzle collector). I showed it to Martin in New York the following week. He was fascinated, and I have five letters from him proposing theories of why it works, the physics of the thing. This is one of tens of thousands of things that Martin thought about.

About those letters: I got about twenty letters a year from Martin over a fifty-year period (you do the math). Sometimes these were elaborate descriptions of tricks of his or others. Sometimes they were brief notes or photocopies of letters others had sent him. Once he sent me a long, wonderful letter about how to write a readable article; it was his way of providing constructive criticism of my paper Statistical Problems in ESP Research (Science, 1978).

Martin interacted. Once, a book about psychic photography, The World of Ted Serios by Jule Eisenbud, M.D., had been sent to Scientific American for review. Martin got in touch with photographer/magician Charles Reynolds, technical expert David Eisendrath, and me, and arranged for us to go see Serios to try to figure out how he did it. We caught Serios cheating. The resulting review was too hot for Scientific American to handle, and the story was published in Popular Photography (October 1967). This was the first of many joint interactions with Martin in the world of psychic debunking. I got to visit two Stanford Research Institute (SRI) scientists, call them Puton and Offtarget, who were investigating psychic Uri Geller. My detailed reports on sloppy statistics and uncontrolled experiments were woven into Martins writings; see his two books in the Confessions of a Psychic series under the pseudonym Uriah Fuller (they even appeared in a legal settlement that Martin won from Offtarget). Martin often asked for help in checking the validity of statistics and in doping out methods for supposedly amazing feats. His cabinet of experts included magicians James Randi and Jerry Andrus, and the psychologist Ray Hyman. It was a lifelong battle for him. In addition to science and stealth, he introduced an important new tool to the field: the horse laugh. He just wouldnt go along with the academic tradition of treating crank science seriously.

Of course, Martin was a pioneer at researching pseudo-, fringe, and controversial science with his

Next page