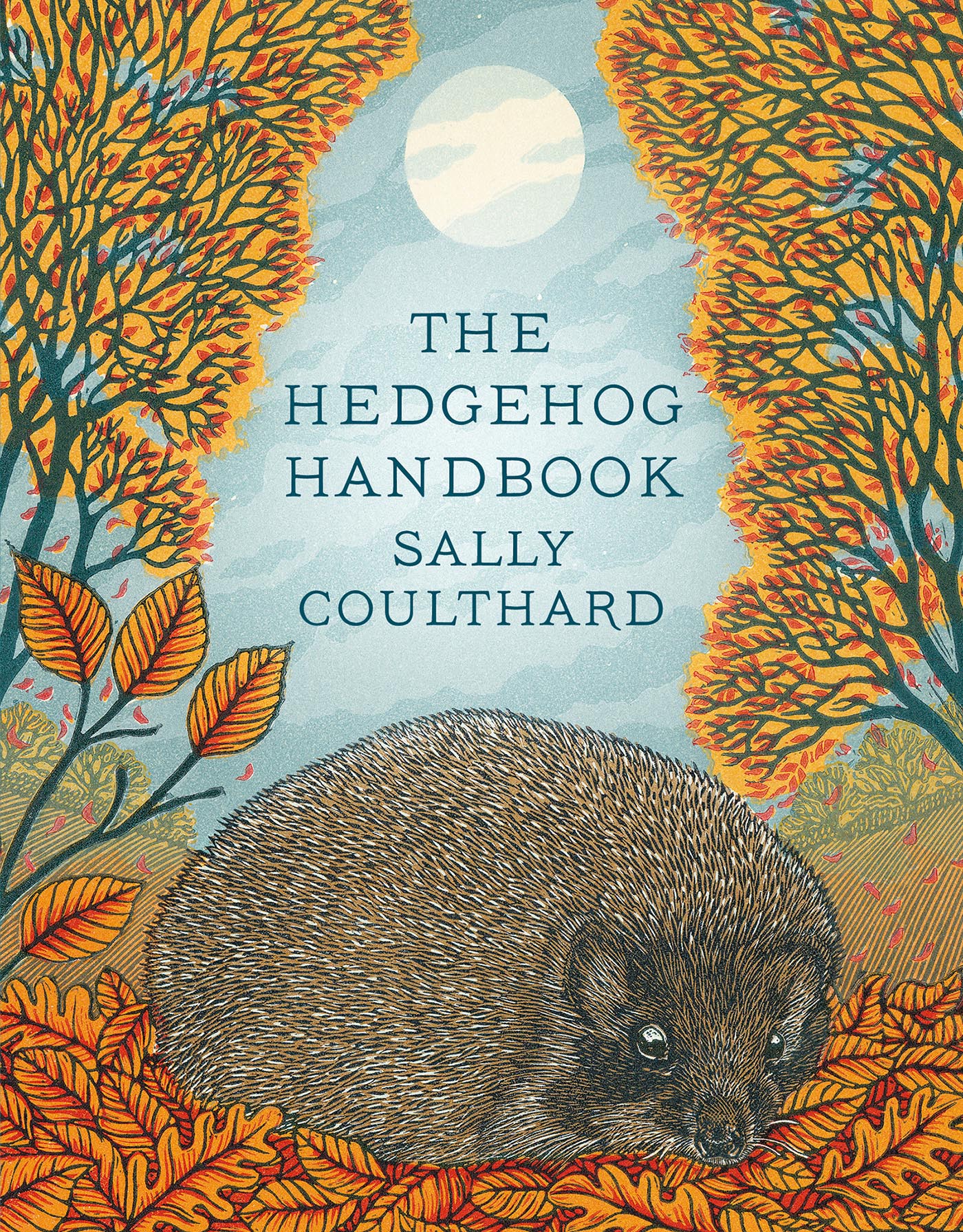

THE HEDGEHOG HANDBOOK

Sally Coulthard

www.readanima.com

A month-by-month celebration of one of the countrysides best-loved creatures.

Full to the brim with fascinating insights, The Hedgehog Handbook explores different facets of this enigmatic and much-admired mammal from its eating and sleeping habits to its literary heritage and what we can do to help preserve this icon of rural life.

Fun, sweet and warm-hearted, The Hedgehog Handbook is the perfect gift for anyone with a penchant for prickles.

CONTENTS

For Jane

Were a nostalgic bunch. Ask anyone over thirty and theyll always tell you that when they were kids, the summers were hotter, people were friendlier and it always snowed at Christmas. Probably not true, but memories have a habit of playing tricks on you.

But what about when people say they never see hedgehogs any more? Was there really a time when our gardens were regularly visited by our prickly friends? The sad fact is that, despite our propensity for rose-tinted glasses, there were more hedgehogs around when we were children. While most adults can remember a childhood visit from a real Mrs Tiggy-Winkle, few kids today have had the pleasure of coming face-to-face with a hedgehog.

And its not just that there are fewer hedgehogs than there were. Its estimated that in the 1950s there were around thirty million hedgehogs in the UK. Now, the best guess is that were down to less than a million . Its something of an understatement to say that not all is as it should be.

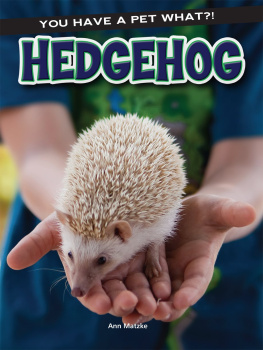

But the aim of this book is not to make you feel hopeless. Far from it. This is a book designed to do two things. The first is to give you a quick glimpse into the habits and lifestyle of one of the most enigmatic wild creatures we know. Hedgehogs are fascinating, theres no getting round it. From their night-time routines to their noisy eating, theyre full of character, vim and rambling charm. With their quiet determination and bristling, bumbling ways, theyre one of the most enduring symbols of the countryside and a traditional, rural way of life. This shy, shuffling animal has captured the imagination of children and grown-ups for centuries, from the timeless stories of Beatrix Potter to modern Instagram sensations such as Biddy the Hedgehog, an African pygmy pet hedgehog with his half a million followers (now sadly deceased, RIP).

But theres also a good reason to know more about hedgehogs only once we understand their nature and biology can we work out whats going wrong and, hopefully, fix it. Its not helpful to talk about hedgehogs being extinct in five, ten, fifteen years time not only does it give that outcome an air of inevitability but, more importantly, we simply dont know whats going to happen. The focus needs to be on helping hedgehogs cope with changed circumstances (i.e. a landscape thats not as hedgehog-friendly as it once was) and doing positive things that help existing hedgehog populations to carry on life as normally as possible (such as creating hedgehog highways and encouraging wilder, more natural areas in gardens).

So, the book takes you through a year in a hedgehogs life, starting in spring, when she wakes from a long winters hibernation. Woven throughout this narrative youll find practical advice on how to help hedgehogs in your own neighbourhood, and more information about their habits, biology and life cycle. If youve picked up this book theres a good chance youre already hooked on hedgehogs. If not, you should be. Theres a growing army of conservationists, volunteers and like-minded people who are passionate about preserving our prickly friend and we always need more recruits

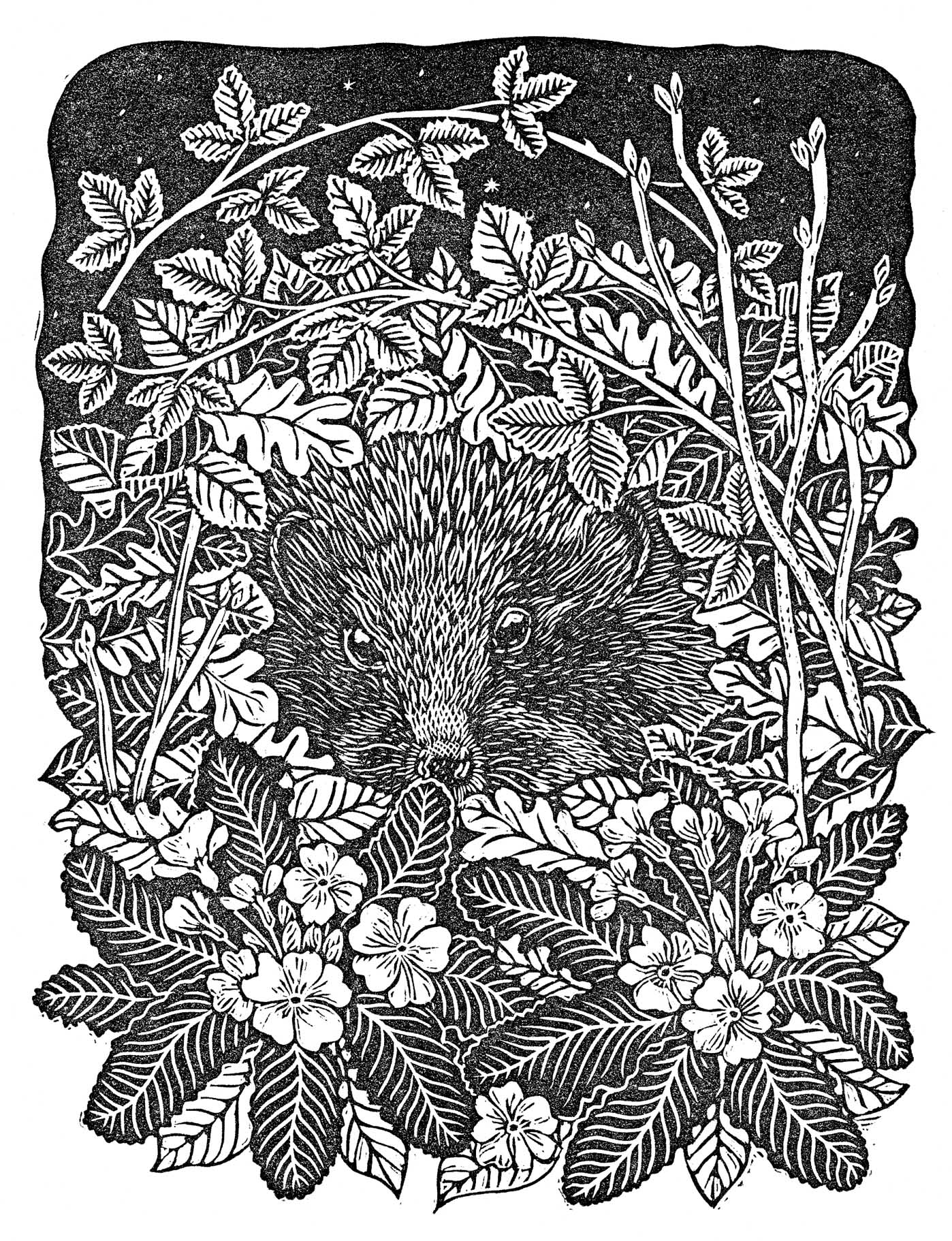

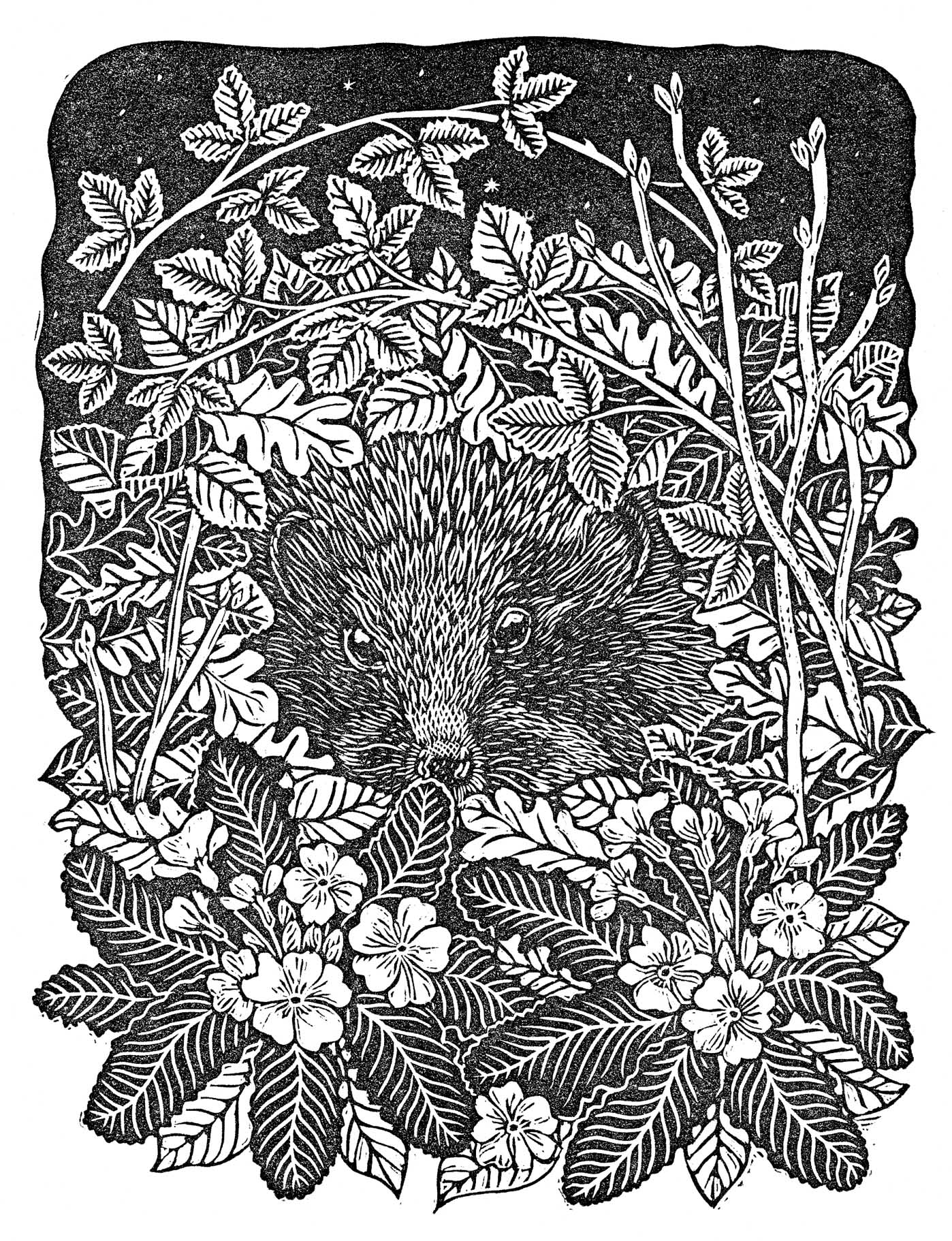

Its March, at last. Winter has loosened her icy grip and there are signs that spring is slowly emerging. Primroses and bluebell leaves push their way through the woodland floor, early bumblebees hum along the clearings, and in the trees rooks repair their unruly nests, shouting as they go.

Like keen shoppers at a spring sale, a handful of creatures are making the most of these lenient days after a long, hard winter. Courting hares fist fight in the open fields. Badgers scramble out of their setts while the cubs snooze underground. Even the odd brimstone butterfly, with his buttery wings, has been seen circling the air after months of ivy-covered sleep.

Come the dusk and, at the bottom of a blackthorn hedge, the tip of a snout appears from a pile of leaves, sniffing the air. Its a hedgehog, woken from three months of enforced isolation, and shes hungry.

The leafy nest has insulated her from the worst excesses of winter but shes also acutely attuned to any changes in the outside temperature. The last few days have been warmer, less hostile, and triggered her wake-up phase a gentle coming to from an entire season of suspended animation; barely breathing, immobile and cold to the touch.

Shes thin. During hibernation, shes lost over a third of her body weight and needs to build up her strength quickly. And so, with the thought of a fat slug or juicy worm whetting her appetite, she shuffles out into the night

The Hedgehog

The English like to think they invented the hedgehog. And, in a funny way, they did. Travel back six hundred years, to the Middle Ages, and you find the first recorded instance of the word hygehoge a simple marriage of hyge (hedge) and hoge (pig). It was a straightforward, no-nonsense name did exactly what it said on the tin and described the creature perfectly: a snuffling, grunting, hog-snouted beastie that liked nothing better than hanging around hedgerows.

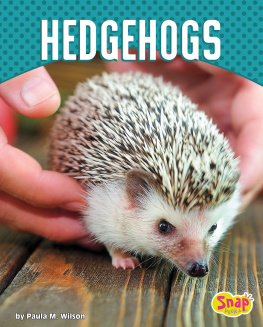

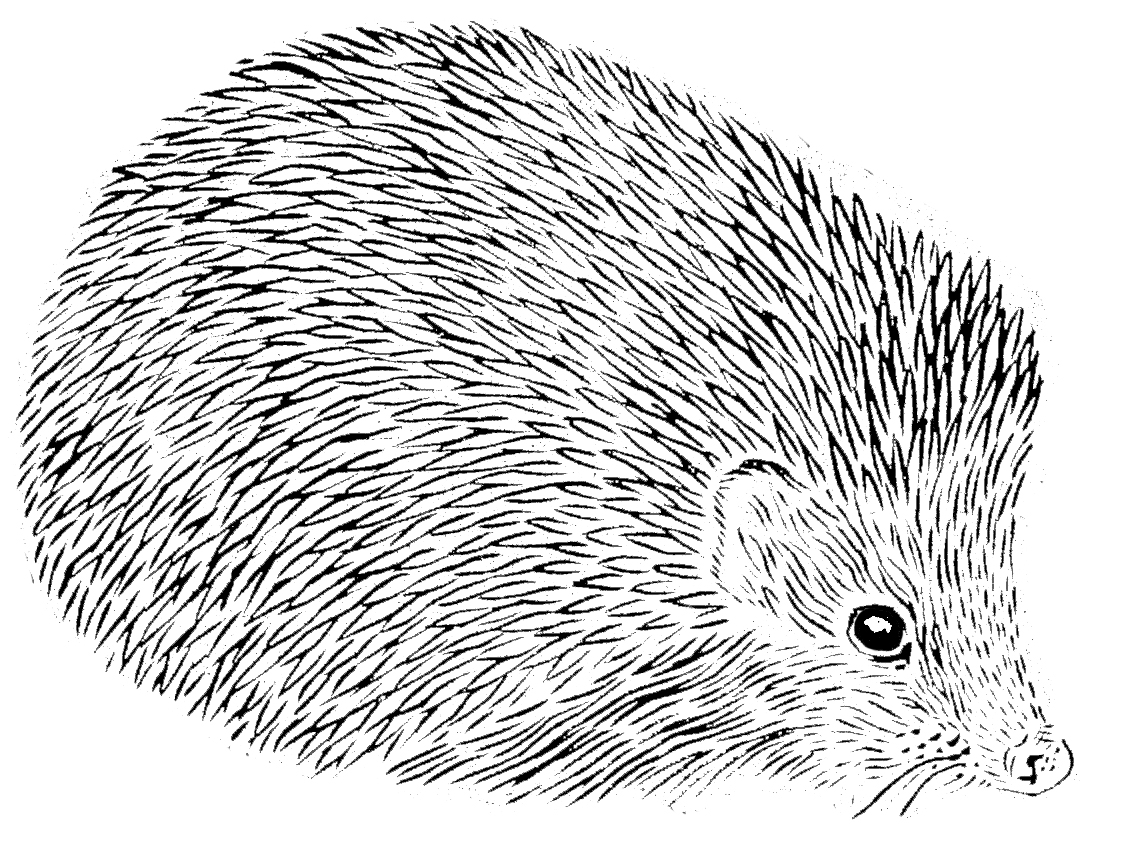

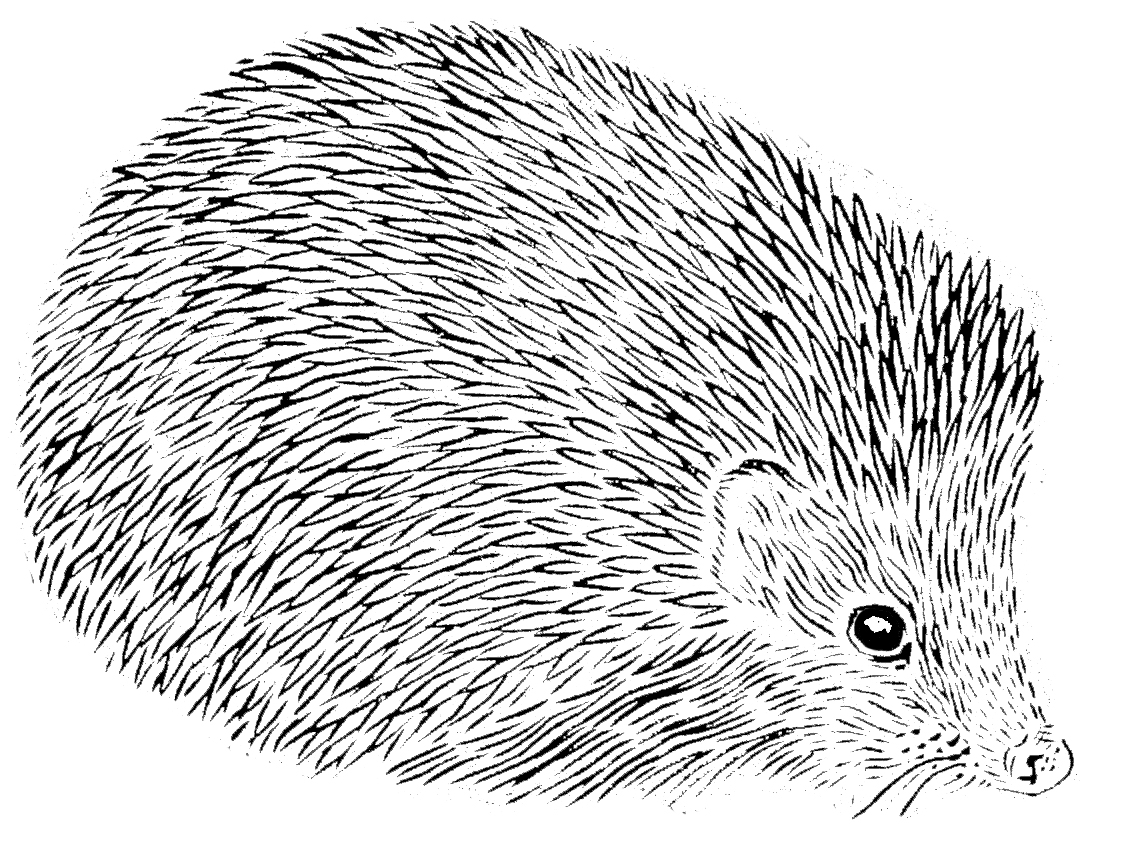

The name stuck. And describes the European hedgehog ( Erinaceus europaeus ) to a T. But nature is never that straightforward. There are, in fact, over fifteen different species of hedgehog scattered across the globe and some of them are not even that hedge-loving. Hedgehogs belong to a family called Erinaceinae , a group of mammals that can be found in terrain as diverse as arid desert, open savannah and lush woodland, and vary in colour from white albino to nearly black.

Despite their spines, hedgehogs share more in common, taxonomically speaking, with shrews and moles than other similar prickly mammals such as porcupines, and the European hedgehog is the biggest species of them all averaging between 450 grams and 1.2 kilograms (12 lb), although you do occasionally see the odd 2-kilogram (4 lb) whopper. At the other end of the spectrum, there are also some tiddlers the African pygmy, for example, the species most commonly kept as a pet, can weigh as little as 200 grams (7 oz) and fits neatly into a teacup.