BLOOMSBURY WILDLIFE

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

This electronic edition published in 2018 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY WILDLIFE and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2018

Copyright James Lowen, 2018

James Lowen has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work

For legal purposes the Image constitute an extension of this copyright page

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for.

ISBN: 978-1-4729-5008-6 (PB)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-5007-9 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-5006-2 (ePDF)

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters.

For all items sold, Bloomsbury Publishing will donate a minimum of 2% of the publishers receipts from sales of licensed titles to RSPB Sales Ltd, the trading subsidiary of the RSPB. Subsequent sellers of this book are not commercial participators for the purpose of Part II of the Charities Act 1992.

Contents

Meet the Hedgehogs

The star of Beatrix Potters The Tale of Mrs Tiggy-Winkle has worked its way into the hearts of successive generations of children and has long been coveted by gardeners for munching slugs. It is little surprise then that the Hedgehog routinely tops polls of favourite UK animals. Yet behind the Hedgehogs appealing front lies a little-known, scarcely seen and ever-rarer mammal with which humans have a contradictory and complex relationship that encompasses reverence and persecution, humour and hope, death and resurrection.

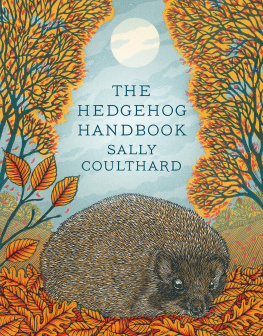

Cute face and spiny body: who can fail to be charmed by the Hedgehog?

There may be no more immediately recognisable European mammal than the Hedgehog Erinaceus europaeus. Packed with prickles, this is not a species that one can mistake. Yet many of us too many of us know the Hedgehog only by image or by icon. Just one-fifth of UK residents claim to have seen a live Hedgehog in the wild far fewer than are familiar with fictional characters such as Mrs Tiggy-Winkle or Sonic.

This is ironic, for Hedgehogs live among us manoeuvring between our gardens, trotting along our pavements and crossing our roads. They are often our closest wild-mammal neighbour, yet we understand so little about them. We have long been fascinated by their resurrection in spring, yet their waking months largely pass us by. Many people devote chunks of their life to caring for Hedgehogs, yet our recent ancestors treated them as vermin. This book seeks to redress the balance, to celebrate Hedgehogs and what they have meant to us across several millennia.

A welcome garden visitor.

Hedgehogs family tree

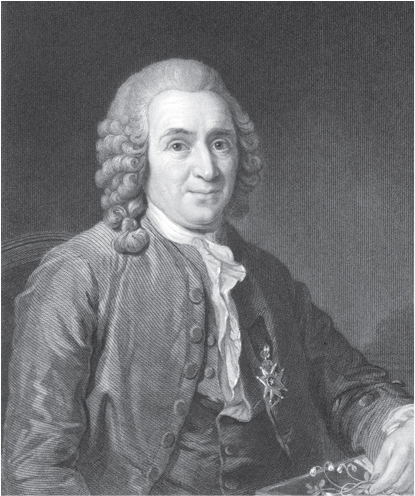

If there is one thing that biologists truly delight in arguing about, it is taxonomy the science of classifying species. In the mid-18th century, a Swedish naturalist named Carl Linnaeus produced a ground-breaking attempt to classify and name all life forms. Many of his decisions have stood the test of time. But with the rise of DNA technology, in particular, scientists are increasingly changing how they group animals (and plants and fungi, and so on). Hedgehogs bear witness to this.

Carl Linnaeus, the godfather of taxonomy.

Until the early 21st century, hedgehogs were associated with moles, shrews and other small mammals within the order Insectivora (literally insect-eaters). Biologists were aware that this grouping was a bit of a dumping ground for mammalian miscellanea not least because many of its members feasted on things other than insects. So there was comparatively little disgruntlement when various components of the Insectivora were spun off into separate groupings. Hedgehogs were granted their very own order, Erinaceomorpha, an accolade that suggested they had no particularly close relatives.

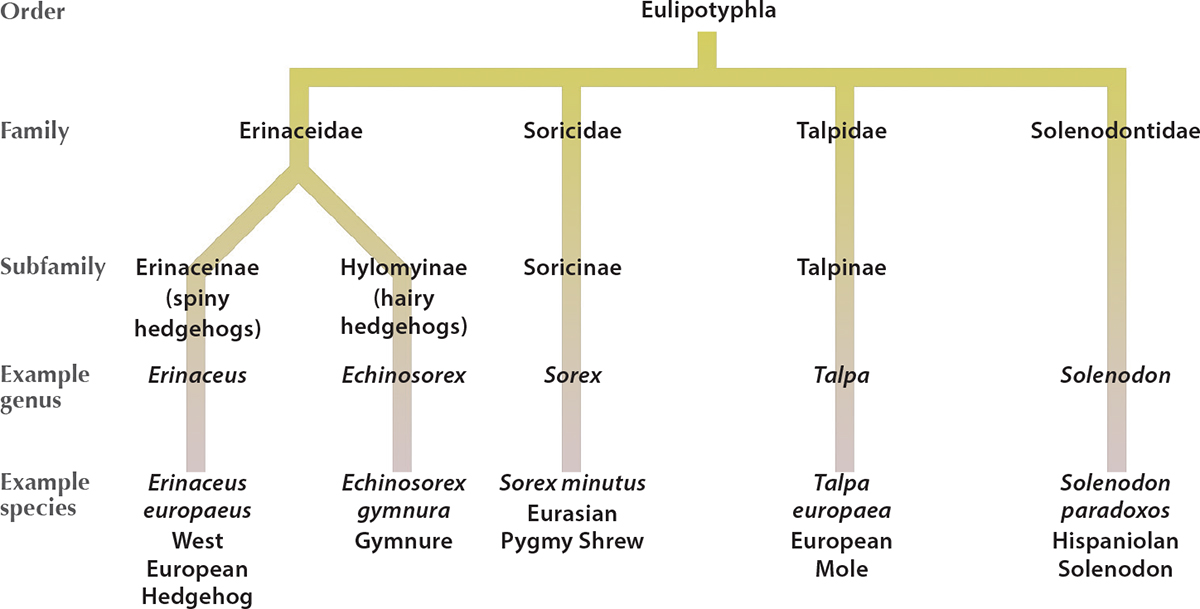

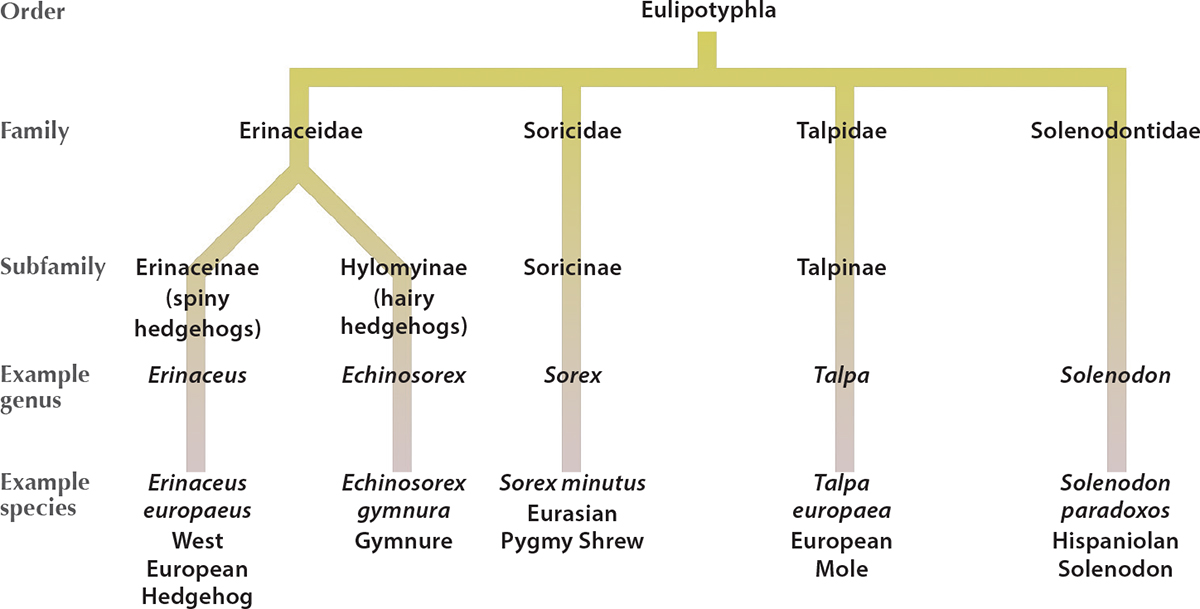

Many biologists think this classification makes sense and have stopped the taxonomic wheel here; however, others consider it too radical. The alternative view is that hedgehogs form Erinaceidae, one of four living families making up the order Eulipotyphla (which means truly fat and blind). The rest of the quartet of families comprises those that house familiar species such as shrews and moles, but also lesser-known mammals such as desmans (bizarre aquatic mammals from Eurasia) and solenodons (odd burrowing animals from Caribbean islands). The family tree above adopts this second approach.

A pointed snout is one clue that shrews (left: Pygmy Shrew) and hedgehogs are close relatives.

Current classification within the order Eulipotyphla

Whichever approach is correct, what does this mean for other conspicuously spiny mammals, such as porcupines, spiny rats, echidnas (spiny anteaters from Australia) and tenrecs (prickly insectivores from Madagascar that are nearly dead ringers for hedgehogs)? Given that spines are a particularly peculiar physical characteristic, you might be forgiven for thinking that all mammals possessing them might be closely related to hedgehogs. But they are not. Porcupines, for example, are part of the rodent family, which contains rats and squirrels. It transpires that all these spiny mammals evolved their unusual outer layer independently a phenomenon that biologists call convergent evolution. The connection between these lookalikes is barely skin-deep.