JUSTICE FOR HEDGEHOGS

JUSTICE FOR HEDGEHOGS

THE BELKNAP PRESS

OF

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

For Reni

ix

I

PART ONE

Independence

PART TWO

Interpretation

PART THREE

Ethics

PART FOUR

Morality

PART FIVE

Politics

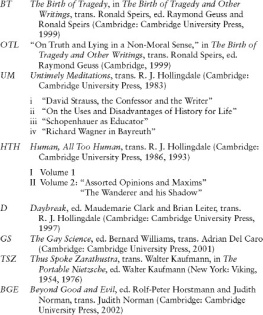

This is not a book about what other people think: it is meant as a standalone argument. It would have been longer and less readable if packed with responses, distinctions, and anticipated objections. But, as an anonymous reader for the Harvard University Press pointed out, it would weaken the argument not to notice the great variety of prominent theories in the several fields the book touches. I compromised by discussing the work of contemporary philosophers in several extended endnotes spread throughout the book. I hope this strategy makes it easier for readers to decide which parts of my argument they wish to locate in the contemporary professional literature. Nevertheless, it proved necessary to anticipate objections more fully in some parts of the text-particularly in Chapter 3, which examines rival positions in greater detail. Readers who are already persuaded that moral skepticism is itself a substantive moral position will not need to linger over those arguments. Chapter i provides a road map of the entire argument and, at the risk of repetition, I have included several interim summaries in the text.

I have been fortunate in attracting critics in the past, and I hope this book will be criticized as powerfully as past books have been. I propose to capitalize on technology by establishing a Web page for my responses and corrections, www.justiceforhedgehogs.net. I cannot promise to post or to respond to all comments, but I will do my best to make additions and corrections that seem called for.

Acknowledging all the help I have had in writing this book is close to the hardest part of writing it. Three anonymous readers for the Press made a host of valuable suggestions. The Boston University Law School sponsored a conference of some thirty papers, organized by James Fleming, to discuss an earlier version of the manuscript. I am unboundedly grateful for that conference; I learned a great deal from the papers that I believe has much improved the book. (I acknowledge, in endnotes, several passages that I changed in response to criticism offered there.) The conference papers are published, together with my response to many of them, in Symposium: justice for Hedgehogs: A Conference on Ronald Forthcoming Book (special issue), Boston University Law Review go, no. 2 (April 2010). Sarah Kitchell, that review's Editor-in-Chief, did an excellent job of editing the collection and making it available to me as quickly as possible. I have not been able to include the bulk of my responses in this book, however, so readers might find it helpful to consult that issue.

Colleagues have been unusually generous. Kit Fine read the discussion of truth in Chapter 8, Terence Irwin the discussion of Plato and Aristotle in Chapter 9, Barbara Hermann the material on Kant in Chapter ii, Thomas Scanlon the section on promising in Chapter 4, Samuel Freeman the discussions of his own work and that of John Rawls in various parts of the book, and Thomas Nagel the many discussions of his views throughout the book. Simon Blackburn and David Wiggins commented helpfully on drafts of my endnote discussions of their opinions. Sharon Street generously discussed her arguments against moral objectivity discussed in the endnotes to Chapter 4. Stephen Guest read the entire manuscript and offered a great many valuable suggestions and corrections. Charles Fried taught a seminar based on the manuscript at the Harvard Law School and shared his and his students' very helpful reactions to it. Michael Smith corresponded with me in further discussion of the issues raised in his Boston University Law Review piece. Kevin Davis and Liam Murphy argued with me about promising. I benefited greatly from discussion of several chapters in the New York University Colloquium on Legal, Political and Social Philosophy, and in a similar Colloquium, organized by Mark Greenberg and Seana Shiffrin, at the UCLA Law School. Drucilla Cornell and Nick Friedman reviewed the manuscript extensively in their forthcoming article "The Significance of Dworkin's Non-Positivist Jurisprudence for Law in the Post-Colony."

I am grateful to the NYU Filomen D'Agostino Foundation for grants enabling me to work on the book during summers. I am grateful to the NYU Law School, also, for its research support program that allowed me to hire a string of excellent research assistants. Those who worked on substantial portions of the book include Mihailis Diamantis, Melis Erdur, Alex Guerrero, Hyunseop Kim, Karl Schafer, Jeff Sebo, and Jonathan Simon. Jeff Sebo reviewed substantially the entire manuscript and offered very valuable critical comments. These assistants, collectively, provided almost all the endnote citations, a contribution for which I am particularly grateful. Irene Brendel made many perceptive contributions to the discussion of interpretation. Lavinia Barbu, the most exceptional assistant I know, has been invaluable in a thousand ways. One more, rather different, acknowledgment. It has been my unmatched good fortune to have as my closest friends three of the greatest philosophers of our time: Thomas Nagel, Thomas Scanlon, and the late Bernard Williams. Their impact on this book is most quickly demonstrated by its index, but I hope it is evident in every page as well.

JUSTICE FOR HEDGEHOGS

Foxes and Hedgehogs

This book defends a large and old philosophical thesis: the unity of value. It is not a plea for animal rights or for punishing greedy fund managers. Its title refers to a line by an ancient Greek poet, Archilochus, that Isaiah Berlin made famous for us. The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.' Value is one big thing. The truth about living well and being good and what is wonderful is not only coherent but mutually supporting: what we think about any one of these must stand up, eventually, to any argument we find compelling about the rest. I try to illustrate the unity of at least ethical and moral values: I describe a theory of what living well is like and what, if we want to live well, we must do for, and not do to, other people.

That idea-that ethical and moral values depend on one another-is a creed; it proposes a way to live. But it is also a large and complex philosophical theory. Intellectual responsibility about value is itself an important value, and we must therefore take up a broad variety of philosophical issues that are not normally treated in the same book. We discuss in different chapters the metaphysics of value, the character of truth, the nature of interpretation, the conditions of genuine agreement and disagreement, the phenomenon of moral responsibility, and the so-called problem of free will as well as more traditional issues of ethical, moral, and legal theory. My overall thesis is unpopular now-the fox has ruled the roost in academic and literary philosophy for many decades, particularly in the Anglo-American tradition.2 Hedgehogs seem naive or charlatans, perhaps even dangerous. I shall try to identify the roots of that popular attitude, the assumptions that account for these suspicions. In this introductory chapter I offer a road map of the argument to come that shows what I take those roots to be.