Library and Archives Canada Cataloguingin Publication

Wilson, Janet, 1952

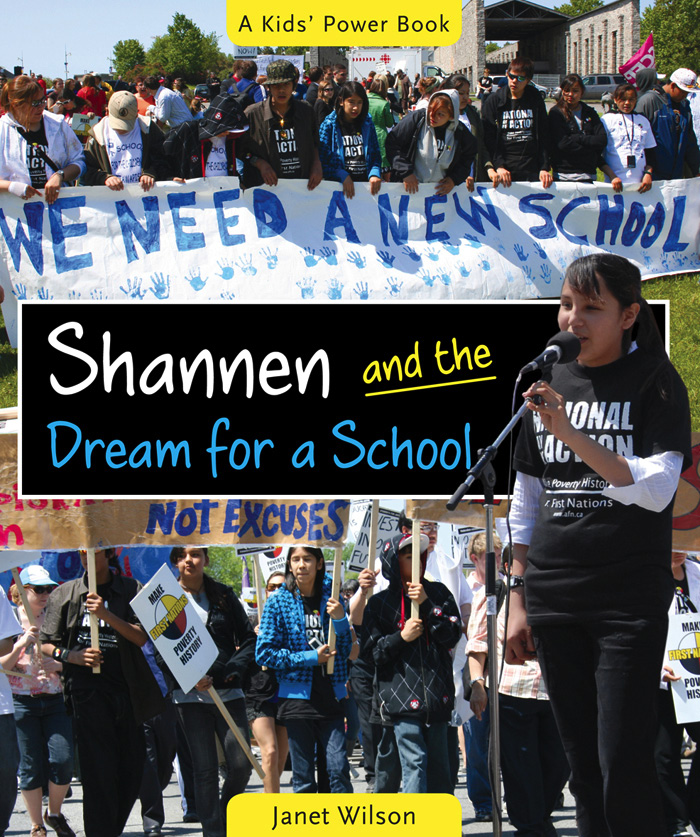

Shannen and the dream for a school /by Janet Wilson.

(The kids power series)

ISBN 978-1-926920-30-6

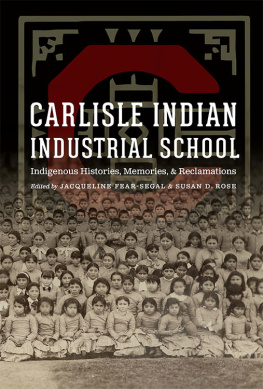

1. Koostachin, Shannen, 1994-2010. 2. Indianactivists

OntarioAttawapiskatBiography. 3. Childrens rights

OntarioAttawapiskatJuvenile literature. 4. CreechildrenEducationOntarioAttawapiskatJuvenile literature.

I. Title. II.Series: Kids power series

E90.K66W552011 j971.00497323092 C2011-904497-8

Copyright 2011 Janet Wilson

Edited by Yasemin Ucar

Designed by MelissaKaita

Icons iStockphoto

Second Story Press gratefullyacknowledges the support of the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Councilfor the Arts for our publishing program. We acknowledge the financialsupport of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund.

Published by

Second Story Press

20 Maud Street, Suite 401

Toronto, ONM5V 2M5

www.secondstorypress.ca

When I shook his hand, I told him that were not going toquit.

Shannen Koostachin, The Globe and Mail

Quote of the Day, May 30, 2008

Authors Note

When you know other children have big comfy schools with hallwaysthat are warm, you feel like you dont count for anything.

Shannen Koostachin, 13, Attawapiskat First Nation, Ontario,Canada

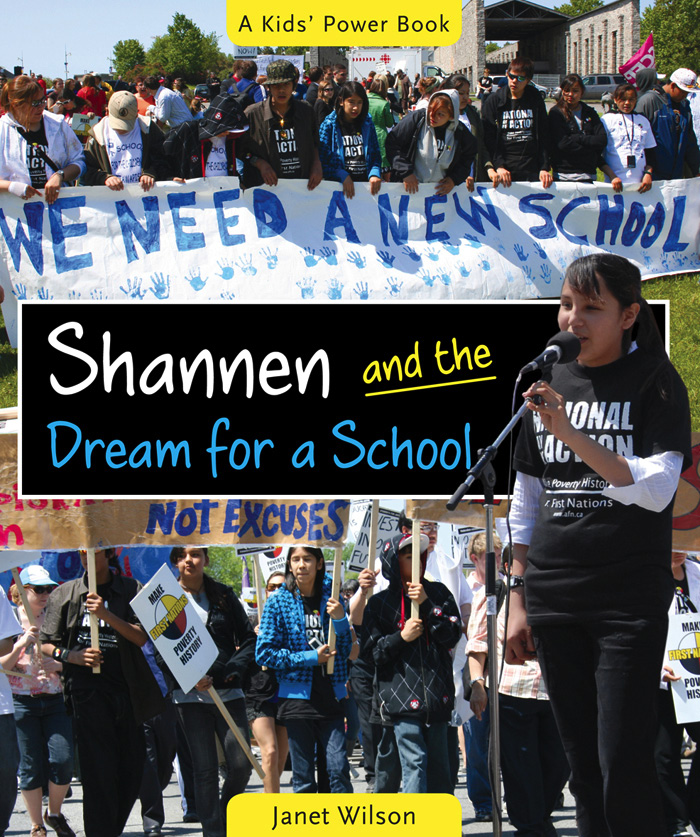

Shannen had adreamthat all First Nations children be educated in decent schools, the kindnon-Native children attend. The story you are about to read is the true story ofShannen and her classmates efforts to get the Canadian government to replacetheir contaminated elementary school in Attawapiskat First Nation, in northernOntario.

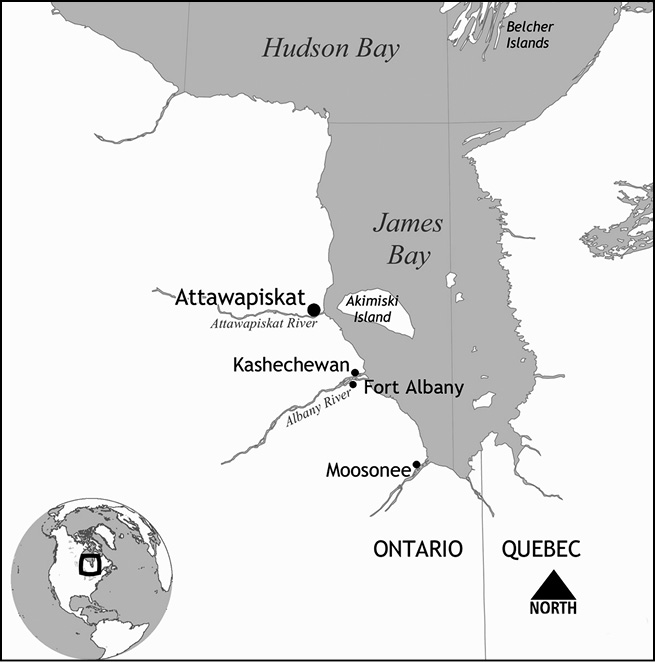

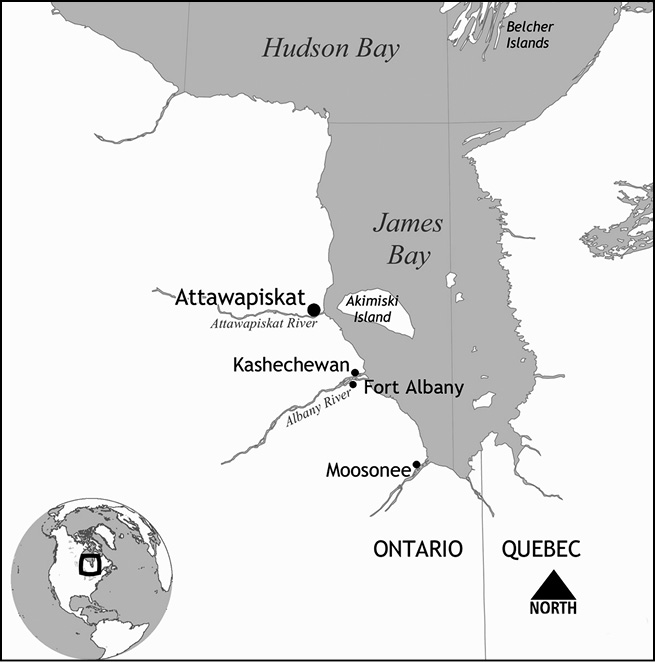

To get to Attawapiskat, imagine traveling north by car or trainuntil the roads and rails end. From there, youd have to take a small airplaneeven farther north over the flat, vast muskeg until you reach the western shoreof James Bay. The reserve of two thousand or so people is at the mouth of theAttawapiskat River.

The events in this story really happened and the characters arereal, however, my telling of the story has been fictionalized. I have imaginedmost of the dialogue, inspired by the recollections of many of the peopleinvolved and, with their blessing, have taken small artistic liberties inrecreating some of the situations. Newspaper articles, speeches, and quotes fromgovernment officials, are accurate, but at times abbreviated.

Attawapiskat, seen here from an airplane, is home toabout 2,000 people.

Prologue

March 9, 2009, Attawapiskat

First Nation, Ontario,Canada

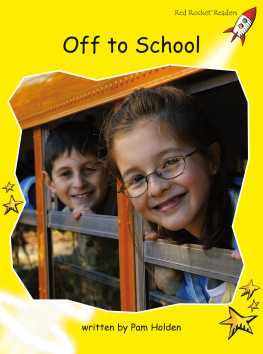

Winter mornings inAttawapiskat are normally quietso quiet that most days the loudest sound otherthan the occasional bark of a dog or the braaap of a snowmobileengine is the squeak, squeak of childrens boots making their way along thesnow-packed road. This was not one of those mornings.

The first bangs and crashes that echoed through the reserve pulledchildren like a magnet from every direction toward the sourcethe old J.R.Nakogee Elementary School. Yellow bulldozers, dump trucks, and prayingmantis-like excavators had driven up the winter ice road along the James Baycoast to take their positions in the schoolyard. In the morning, the childrenpressed moose-hide mittens against the chain-link fence and peered throughcracks in the black plastic tarpaulin. Older kids scrabbled up snow banks to geta better look at the demolition siteuntil finally the children were shooed awayto their classes in the nearby portables.

Schoolchildren had walked past the ghostly gray building everymorning and every afternoon for so long they barely noticed it. Most didntremember the day, nine years before, when angry and frustrated parents nailedboards over the windows and doors, and refused to allow their children to enterthe building. Since then, the only children who had been inside were thosedaring enough to lower themselves through a hole in the roof to play in therooms some say were haunted with the spirits of departed children.

This was a sad day for those residents of Attawapiskat whoremembered when J.R. Nakogee School first opened in 1976. Children had beenexcited to attend school in the bright and clean building that had electricityand indoor plumbingluxuries only a few Attawapiskat households enjoyed at thattime. Parents had been happy that their children would now stay in the communityto be educated instead of being sent far away to school in the south. The schoolbecame the heart of the community, where everyone had come together for Powwows,Feasts, socials, square dances, monster bingos, and other special events. Thepeople of Attawapiskat had been proud of their new school.

The problems began with the dreadful discovery that the undergroundiron pipe carrying diesel fuel to the schools furnace had leaked tens ofthousands of litres into the soil. For years, teachers and parents complainedthat their children were tired, sick, and irritable. Even though health reportson the spill indicated that dangerous chemicals had been detected, the Canadiangovernment, which was responsible for maintenance, declared that there were nohealth concerns in the school. Finally, the parents said, Enough is enough!and the building was boarded up, and had remained closed ever since.

On this day, nine years later, the children sitting in nearbyportables were finding it hard to concentrate with all the noise of thedemolition. Unlike their parents, many of the students were not feeling sad. Tothem, the old school was just a haunting reminder of what a real school waslikewith a library, a gym, and halls, all under the same roof. Once thebuilding was finally gone, maybe they would get a new school. Maybe theywouldnt have to ask each other, If children in other communities have decentschools, why dont we?

J.R. Nakogee School

The demolition ofJ.R. Nakogee School