To Andrea

With mere rocks in their hands,

they stun the world

and come to us like good tidings.

Bursting with love and anger,

they defy, and topple,

while we remain a herd of polar bears

bundled against weather

NIZAR QABBANI, CHILDREN BEARING ROCKS

CONTENTS

This is a work of nonfiction. As such there are no imagined conversations or composite characters. Everything in this book is the result of interviews, archival research, news accounts, and primary and secondary sources. All facts in the book have been subject to rigorous fact-checking, including verification with the dozens of people interviewed in the course of the reporting.

That said, much of the book relies on the reflections of people who were in places where neither I nor any other journalist was present as witness. Thus, of course, not every detail can be independently verified, in particular old and sometimes selective memories that describe small details, or unrecorded conversations. However, I have made significant efforts to corroborate the stories captured for this book through multiple accounts. This is the case in particular for incidents that may be especially difficult for readers, such as the circumstances surrounding the death of a child in a refugee camp during the first Palestinian intifada. In such cases I relied on a combination of the available recordbooks, newspaper and magazine articles, scholarly papers, human rights reports, United Nations records, and eyewitness accountsto build a multiple-sourced narrative.

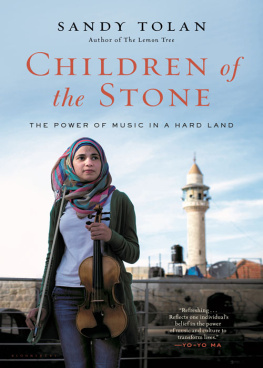

This book tells the story of Palestinian children learning and playing music in a war zone. It is therefore inherently about one peoples tragedies, dreams, artistic triumphs, struggle against a military occupation, and aspirations for freedom, and for an ordinary life. Readers should not expect the traditional journalistic approachthat is, the parallel narratives of Palestinians and Israelis. Rather, the story is told largely through the eyes and experiences of a remarkable group of children and of the visionary Palestinian musician at the heart of this book. Still, in all of the stories the book conveys, and especially in the sections providing historical context, I have tried my best to apply my own personal and professional journalistic standards of rigor, accuracy, and fair-mindedness.

For the most part the story is told chronologically. In rare cases, for ease of reading, I have juxtaposed events that may not have happened one right after the other. In those instances I have noted this in the source notes.

The bulk of the research and reporting took place from 2009 to 2014 and grew out of a feature story I produced for National Public Radio in 1998. For more details, see the acknowledgments and source notes.

December 2009

Pronto Italian Restaurant, Ramallah, West Bank

It was a chance encounter, in December 2009, at an Italian restaurant in the West Bank. I was in Ramallah, working on a story on the dim chances for genuine Middle East peace. I was standing with two fellow journalists, looking for an open table, when I heard my name called out from across the restaurant.

Sandy! Sandy!

I looked at the bearded young man sitting at a corner table. He was beaming at me. I didnt recognize him. He pointed to himself: Ramzi!

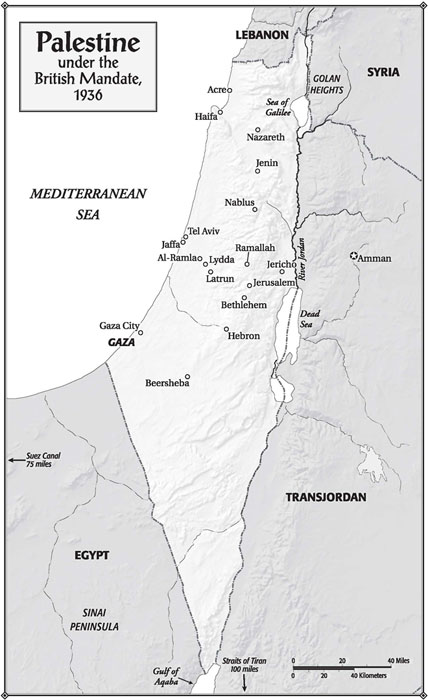

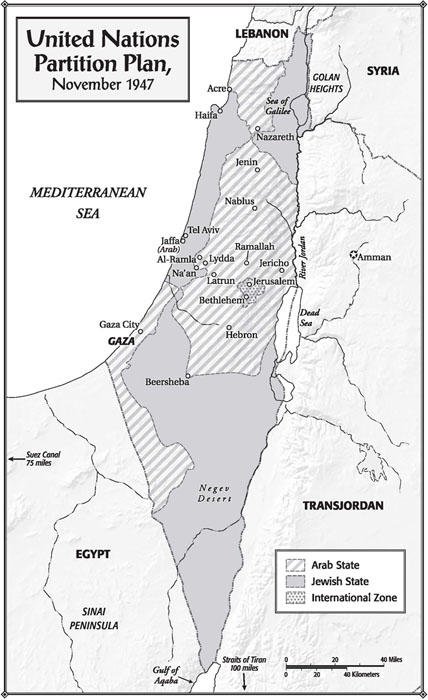

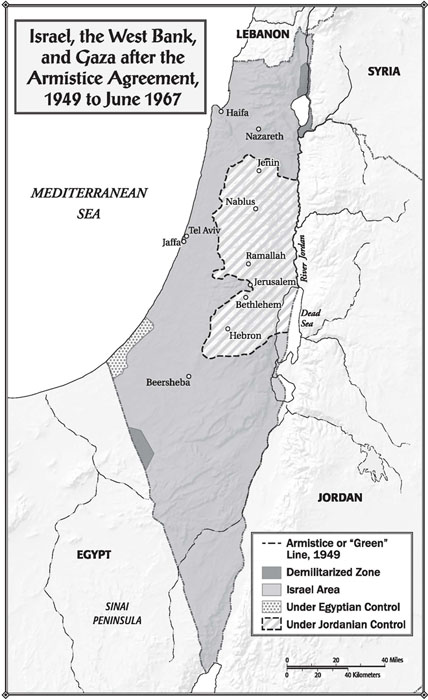

I hadnt seen him in nearly a decade. Ramzi Hussein Aburedwan had been a child of war, one of thousands of Palestinian children who threw stones at Israeli forces during the six years of the intifada (198793; later known as the First Intifada), the uprising against Israels occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. At age eight, Ramzi had been immortalized in one of the most iconic images of the era: a shaggy-haired David with fear and resolve in his eyes, unleashing a stone at an unseen Goliath.

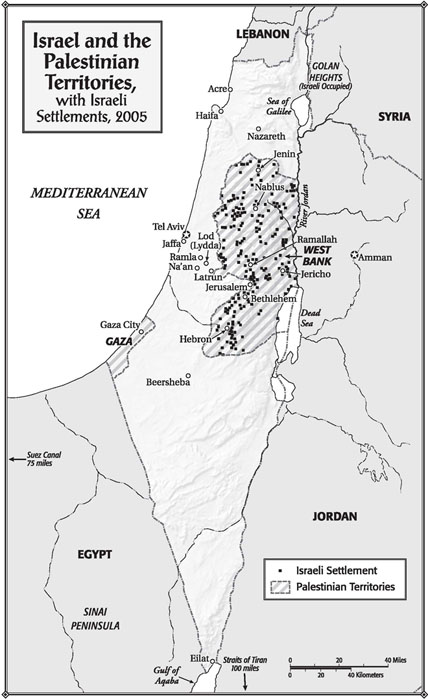

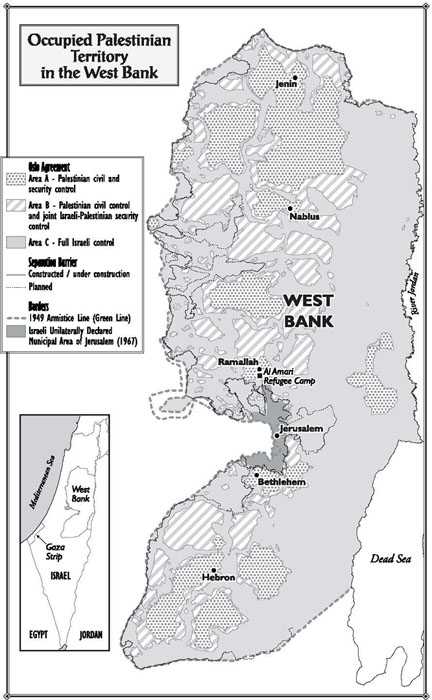

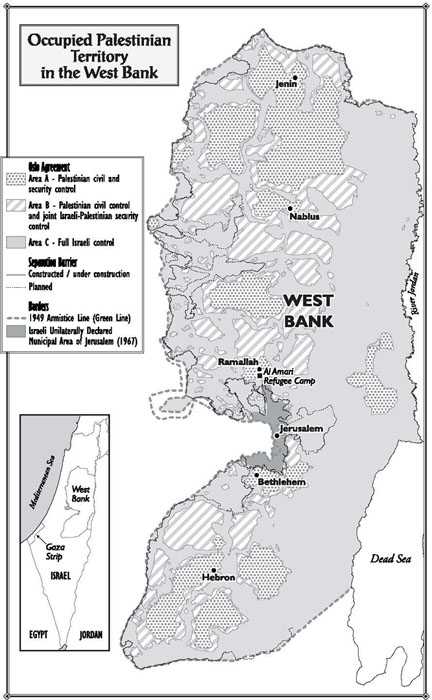

By the time I met Ramzi in 1998, the intifada was over. He was a skinny, clean-shaven eighteen-year-old who lived with his grandparents in the Al Amari refugee camp on the outskirts of Ramallah. No longer was he sneaking through the camp, hurling rocks at soldiers and dashing from rooftop to rooftop to escape. Now, still relatively early in the Oslo peace process, Palestinians long in exile were returning to the West Bank to help build a state of their own. New cultural institutions were springing up, and Ramzi suddenly had a chance to study a long-held passion: music. He had laid down his stones and, with the help of two middle-class Palestinian mentors, picked up a viola.

Within a year, posters around Ramallah showed little Ramzi, throwing the stone, alongside an image of Ramzi as a young man, pulling a bow across his viola strings. The poster announced the arrival of the new National Conservatory of Music. It looked like an advertisement for a newly independent Palestine.

In that winter of early 1998, I sought out Ramzi in the refugee camp where he lived with his family in their modest plaster-and-cinder-block home. I recorded his music and his memories of the intifada. He remained proud of his stone-throwing days, echoing the sentiments of many Palestinians who believed, then, that the stone would lead to their liberation. I wish I could collect all of the stones I threw and frame them or put them on the wall or put them in my own museum, he told me then. Because I was only a child. And all I had was a stone.

Ramzis playing was crude and halting; at eighteen, hed barely had a year of practice. More vivid were his memories of racing through the warrens of the camp during the intifada as one of the children of the stones, as Abu Jihad, the assassinated Palestinian revolutionary, called Ramzis generation. Most striking of all was the teenagers vision to transform the lives of children and show the world what his people could accomplish. I want to see many conservatories opening up in all of Palestine, so that people can learn to play, Ramzi told me one cold gray afternoon, looking out his window at the narrow alley in the refugee camp. And I want for children to understand that theres something called a viola and a violin. I want people to see that we Palestinians are capable. We are like everybody else in the world. We can do a lot. I hope one day Ill be a teacher and a professional viola player. I hope well have a big orchestra and well tour the world in the name of Palestine. I want to show the world that we are here, on the map.

Later that spring of 1998, around the time my story about Ramzi aired on National Public Radio, he landed a coveted scholarship to study the viola at a music conservatory in Angers, France.

We kept in contact for a couple of years. I followed his progress at Angers. Id heard hed started a traveling band, playing mostly Arabic music, while he continued to learn classical viola at the French conservatory.

Eventually, we lost touchuntil that night at the restaurant in Ramallah.

Next page