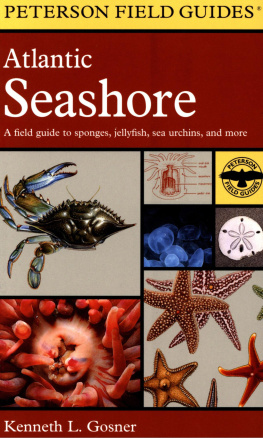

Copyright 1978 by Kenneth L. Gosner

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

PETERSON FIELD GUIDES and PETERSON FIELD GUIDE SERIES are registered trademarks of Houghton Mifflin Company.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gosner, Kenneth L., 1925

A field guide to atlantic seashore.

(The Peterson field guide series; 24)

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Seashore biology. 2. Marine invertebrates-Identification. 3. Coastal floraIdentification.

I. Title.

QH95.7.067 1979 574.909'4'6 78-14784

ISBN 0-395-24379-3 (hardbound)

ISBN 0-618-00209-X (paperbound)

ISBN 978-0-618-00209-2 (paperbound)

eISBN 978-0-544-53085-0

v1.0517

For my father and mother,

who encouraged

independence and curiosity.

Editors Note

T HE BEACHCOMBER tends to be a generalist. If he is ornithologically inclineda birderhe spots the sandpipers, gulls, and terns and consults his Field Guide to the Birds. Those few flowers that invade the dunes or the salt marshes above the line of sea wrack, he will find in A Field Guide to the Wildflowers. However, that leaves a great gapthe seaweeds and the many forms of invertebrate life that live along the edge of the sea in wading or snorkeling depths, and also some of the denizens of deeper waters that are often cast ashore by the waves. There is, of course, A Field Guide to the Shells by Percy Morris, but aside from a partial overlap in the Mollusca, the present Field Guide by Kenneth Gosner fills the void, describing and illustrating not only the seaweeds but also 19 major groups or phyla of invertebrates, some of whichsea anemones, sand dollars, crabs, and barnaclesare rather familiar, and othersbryozoans, amphipods, tunicates, medusae, and comb jellieswhich are not.

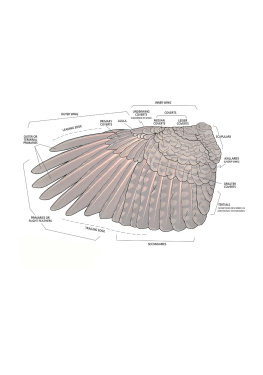

The Peterson Identification System, which emphasizes distinctions between similar species, pointing to critical field marks or recognition characteristics with little arrows, was developed originally in the bird guides and was later extended to cover the whole spectrum of natural history. It is a visual rather than phylogenetic approach wherein similar but unrelated forms may often be shown on the same plate for ready comparison. This technique is here applied to the identification of intertidal life.

Although this guide is designed primarily to cover the area from the Bay of Fundy in Maritime Canada to Cape Hatteras in North Carolina, many of the forms describedor their counterpartswill be found southward to the West Indies while others may range northward to the Arctic.

Kenneth Gosner is one of those rare biologists who is equally skilled as an artist. In fact, biological illustrators competent to handle certain subjects are even harder to come by than academic specialists in the same field. During my many visits to the editorial offices at Houghton Mifflin to monitor the progress of this and other field guides, I have marvelled at the color plates that Kenneth Gosner submitted. There is no room for happy accident in this kind of illustration. It must be highly controlled, and because of the evanescent nature of color and form of some of the marine animals when out of the water it becomes almost an act of legerdemain to translate them to paper.

A good drawing is usually more helpful in identification than a photograph. The latter is a record of a single moment, subject to the vagaries of chance, angle, light, and the limitations of latitude in color film. On the other hand, a drawing is a composite of the artists past experience, in which he can emphasize the important and edit out the irrelevant if he chooses.

The illustrations and text in this Field Guide which depict and describe the incredible variety of treasures to be found in the tide pools and intertidal flats have demanded a staggering amount of field work on the part of Kenneth Gosner. But do not be an armchair marine biologist and be satisfied with merely thumbing through the plates, attractive as they are. Take the book with you to the shore and use it. And do not confine your seaside sorties to the summer beach; there are things to be found at all seasons.

There has been a breakthrough in environmental awareness in recent years. When the first astronaut put his foot on the moon, millions of people became suddenly aware of the uniqueness and isolation of our planet Earth, the only world we will ever have. Ours is a fragile world, whose seas are suffering ecological attrition on a global scale.

The problems of survival of whales, porpoises, and seals are easily dramatized and a number of new conservation organizations have arisen to publicize their plight. But the lesser organisms of the tide pools and the shore are no less important in an evolutionary sense, and they are no less vulnerable. They send out signals when the sea is abused by pollution, exploitation, or some other form of neglect. Inevitably the beachcombing naturalist becomes a monitor of the marine environment.

R OGER T ORY P ETERSON

Acknowledgments

T HIS BOOK is to some degree the product of other peoples efforts. My debt begins with the generations of naturalists who have studied and written about the plants and animals of this coast. The zoological part of this literature is cited in some detail in my Guide to Identification of Marine and Estuarine Invertebrates published in 1971. I began work on the present book almost immediately afterward, and the earlier volume served as a technical base for this one; therefore the 80-odd specialists who read parts of that book in manuscript, and are acknowledged therein, should be thanked again. More directly I am grateful to the following for critical comments on parts of this guide; the entire botanical section was examined by John M. Kingsbury, Arthur C. Mathieson, Jonathan E. Taylor, Jacques S. Zaneveld, and Robert L. Vadas; the nudibranch parts were read by Larry G. Rivest, Terrance Harris, Alan M. Kuzirian, and Brian R. Rivest, and the echinoderm section by John H. Dearborn. Ann Frame not only strove valiantly with the polychaete material but loaned most of the specimens used in making the drawings of those worms. While these readers have materially improved the guide, they are in no way responsible for the errors I have managed to insert despite their efforts.

For additional loans of specimens I want to thank Henry Roberts and Mike Carpenter (U.S. National Museum), Robert Robertson (The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia), Rosalie M. Vogel (Virginia Institute of Marine Science), Jerry Thurman, William Old, William K. Emerson, and, especially, Harold Feinberg (The American Museum of Natural History). Clark T. Rogerson gave me free access to herbarium materials at The New York Botanical Garden.

Requests for information on systematics, distribution, and other matters were generously responded to by Frederick M. Bayer, E. L. Bousfield, Louise Bush, Maureen E. Downey, Clay Gifford, Don Kunkle, Robert E. Knowlton, Frank Maturo, Byron Morris, Patrick Purcell, John B. Pearce and colleagues, Kenneth R. H. Read, Emery F. Swan, Lowell P. Thomas, Henry Tyler, Pierre Trudel, Dana E. Wallace, Marvin L. Wass, Austin Williams, David L. Pawson, and Harold H. Plough.

I owe a special debt to the commercial fishermen of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts who have taken me to sea with them, given me the pleasure of their company, sometimes fed me, and allowed me to pick over their vastly miscellaneous catches. Without this privilege I would never have seen many of the invertebrate inhabitants of this coast in other than a wizened, pickled state. Specifically I want to thank Bert Maxon, the Schnoor brothers, Norman Sickles (Jr. and Sr.), Barry Irwin, George Boyce, Jack Slater, Richard Robbins, Howard Bogan, and others whose names I have lost or never knew at Belford, Shark River, and Point Pleasant, New Jersey; Thomas Lou Hallock, Eldon Willing, Eugene Wheatley, and Alfred Biddlecomb of Virginia and Maryland; Caroll Willis and others at Beaufort and Atlantic, North Carolina; Gabe, Andrew, Charlie, and Mike Gargano of Long Island Sound; Alexander Lindall and additional hardy seamen at Cundys Harbor, Maine; Morrison (Captain Motto) Gisclair and other shrimpers at Golden Meadow and Grand Isle, Louisiana. I am also grateful to the following for putting me in touch with some of the above men or in other ways aiding my field work: Tan Estay, W. Herke, David W. Frame, Robert B. Chapoton, C. M. Cubbage, Harold Haskins, Fred Hersom, as well as Roy Rafter of the Maryland Tidewater Police. The officers and crews of the Coast Guard buoy tenders Arbutus, Red Beach, and Firebush made me welcome on their vessels, and I thank them.

Next page