IN ACKNOWLEDGING the fact that a book is never the product of one persons thoughts and capabilities, I would like to give credit where it is due, first to my parents for the advantages to which I was exposed and the encouragement they always gave me; to my husband and children for their understanding; to my teachers and students (who in a sense were my teachers too).

Had it not been for Helen Vail the book would probably never have had a beginning, so to her my thanks for so much patience. With pencil poised above a stenographic notebook and her great eyes pinned on mine, the halting sentences were dragged from me for the first draft. To Alzora Rutter I can never express my gratitude for the typing of several more drafts and the endless hours of editing and suggestions which led to many improvements in the manuscript. My particular thanks go to Dr. Eugene Ching of the Department of East Asian Languages at Ohio State University for his advice concerning the lesson on characters. His vast knowledge assured the accuracy of the text and of the phrases which I wanted to include.

To James Cahill, former Curator of Chinese Art at the Freer Gallery in Washington, D.C., I owe the most humble thanks for giving of his valuable time and talents in writing the preface to this book. To his generosity of expression I can only answer the Chinese way: Ke tou, ke tou!

I wish to express my appreciation also for permission to quote from three of my favorite books: The Chinese on the Art of Painting by Osvald Siren; Chinese Calligraphy by Chiang Yee, published by Methuen and Co., Ltd. ; and The Tao of Painting: A Study of the Ritual Disposition of Chinese Painting (translation of The Mustard-Seed Garden ) by Mai-mai Sze, Bollingen Series, XLIX, Pantheon Books.

Bibliography

Cahill, James: Chinese Painting, a Skira book distributed by World Publishing Co., Cleveland, 1960.

Chang Shu-chi: Painting in the Chinese Manner , The Viking Press, New York, 1960.

Chiang Yee: Chinese Calligraphy, Methuen and Co., London, 1938.

: The Chinese Eye, W. W. Norton and Co., New York, 1935.

Fei Cheng-wu: Brush Drawing in the Chinese Manner, How To Do It Series, Studio Publications, New York, 1956.

Hawley, W. M.: Study Charts for Chinese. Characters, W. M. Hawley, California.

Kuo Hsi: An Essay on Landscape Painting, Wisdom of the East Series, John Murray, New York, 1935.

MacKenzie, Finlay: Chinese Art, Spring Art Books, Spring House, London, 1961.

Sakanishi, Shio: The Spirit of the Brush, Wisdom of the East Series, John Murray, New York, 1939.

Siren, Osvald: The Chinese on the Art of Painting, Henry Vetch, Peking, 1936.

Swann, Peter C.: Chinese Painting, Universe Books, New York, 1958.

Sze, Mai-mai: The Tao of Painting, Bollingen Series, Pantheon Books, New York, 1956.

Van Briessen, Fritz: The Way of the Brush, Charles E. Tuttle Co., Rutland, Vermont and Tokyo, Japan, 1962.

Wiese, Kurt: You Can Write Chinese, The Viking Press, New York, 1945.

Willetts, William: Chinese Art, Volumes I and II, Pelican Books, London, 1958.

Materials & Equipment

THE CHINESE paint on a flat, horizontal surface such as a table. You should work on a large table or desk at a comfortable height and sit on a straight chair. Cover the table with a piece of smooth white plastic or oilcloth. It is easy to wash the ink off such a surface, and it makes a good background for your work. The ink may not come out of fabrics unless washed immediately, so wear a smock or apron.

You may wish to buy supplies in a boxed set which usually includes the following items: an inkstone, a stick of ink, a water well, two or three brushes, a chop, and chop ink, all packed in one convenient carrying case. These pieces may also be bought separately but, except in the case of the brushes, the sets are usually quite adequate for the beginner. The inkstone is simply a slab of stone (sometimes made of a composition) polished to a smooth surface, on which the ink stick is ground. The ink stick is made by a process in which pine soot and gum are combined in a mold and allowed to harden into the stick form. A water well is a small porcelain block, pierced by two tiny holes. This is immersed in water until it is full, and then by holding a finger over one hole, water may be released drop by drop onto the ink stone as the finger is lifted. A water bowl and spoon may be used instead to place the water on the stone.

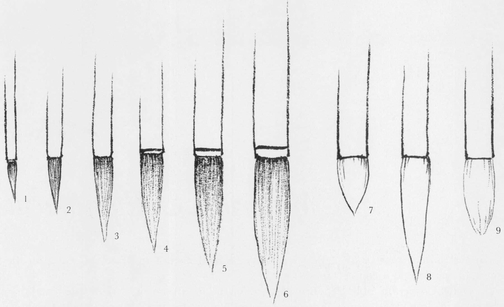

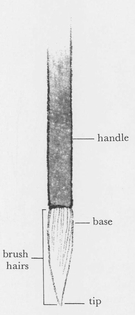

Brushes are made in all possible sizes and qualities; therefore I would like to emphasize that it is better to have quality than quantity, if you must choose. Most brushes available in this country are from Japan but are made in the same way as the Chinese brush. Generally the handle is made of bamboo, and the hairs are of wolf, deer, goat, sable, or rabbit. Different types of hairs are required for different kinds of work. The chart in Fig. 1, illustrating the various brushes you should have, may be used to compare the sizes of your brushes to the sizes you will need. They need not be exactly the same size, but they should be close. Brushes 1 through 6 are sable or wolf hair, and brushes 7 through 9 are rabbit or goat hair. At first you will use brushes No. 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7, but later you will want to add No. 3, 5, 8, and 9. A recommended supply of brushes for the beginner is three of No. 1 or 2, two of No. 7, a minimum of four (six would be better) of No. 9, and one each of the others. The numbers used in the chart are only for reference in this book. Fig. 2 illustrates the various parts of the brush. Do not try to use the Western type of water-color brush for this kind of painting. The hairs are not cut in the same way (to a fine point), and it cannot produce the proper strokes.

Accessories (Fig. 3) which are not really necessary but nice to have are: a compartmented water bowl and spoon, a brush rest, weights, and a jar to hold brushes when not in use. For mixing ink washes and colors you should have a few small shallow bowls or saucers. These may be of glass or china (preferably white) and approximately three inches in diameter and one-half or one inch deep. At a later date you will undoubtedly want colors. The most convenient I have found are a Japanese product which comes ready to use in small white porcelain bowls. They may be purchased separately or by the set.

It is possible to find paper in many qualities, of two distinct types: absorbent and non-absorbent. Both types are usually made from the pulp of rice or bamboo fibers, but nowadays some is manufactured from cotton fibers. Each variety and quality of paper has its own particular use, and by experimenting a little you will find the types which suit you best. For practice work, however, we find that common newsprint (the paper used for printing newspapers) is by far the most useful. It is of just the right absorbency and cheap enough to be bought in large quantities. Any paper company will sell it to you by the pound. Have it cut to size, 12 18. You will find this much less expensive than the tablet form found in most stationery shops.