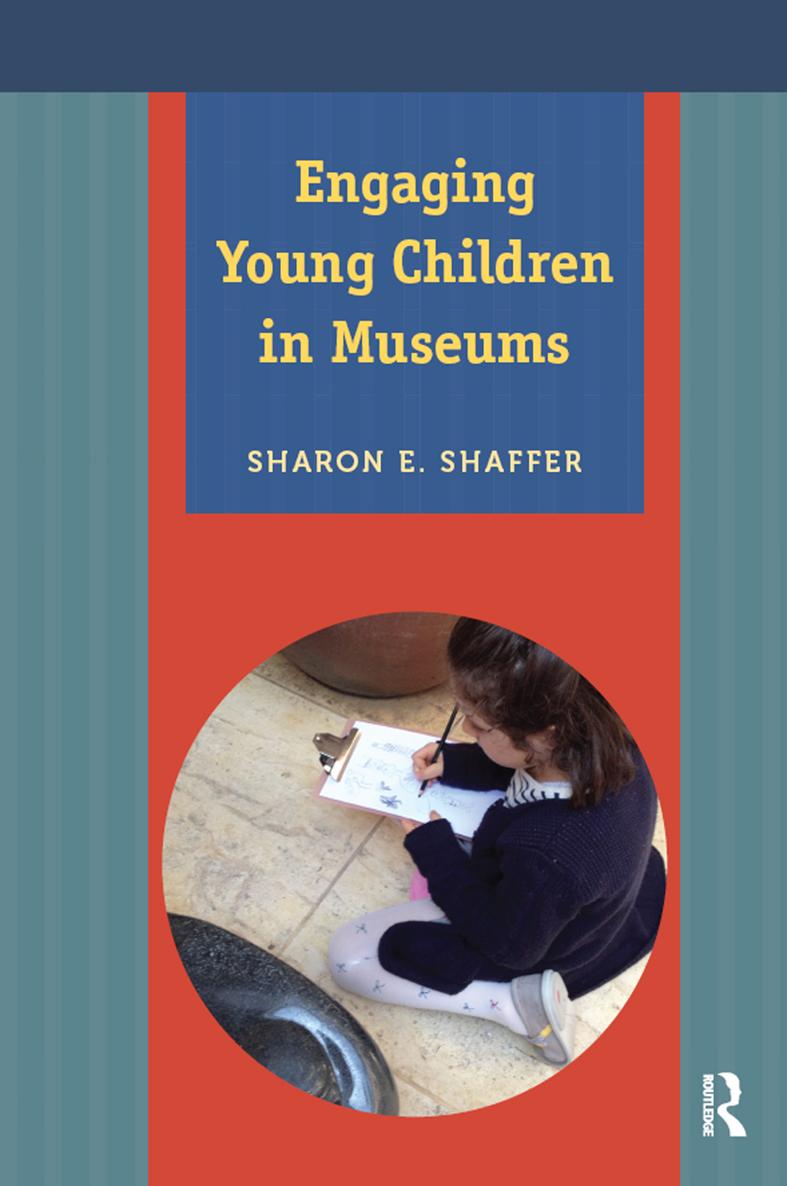

Engaging Young Children in Museums

To the Founding Board of the Smithsonian Early Enrichment Center for trusting me to bring their vision to fruition

Engaging Young Children in Museums

Sharon E. Shaffer

First published 2015 by Left Coast Press, Inc.

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2015 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shaffer, Sharon E., 1950-

Engaging young children in museums / Sharon E. Shaffer.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61132-198-2 (hardback : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-61132-199-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-61132-200-2 (institutional ebook)

ISBN 978-1-62958-042-5 (consumer ebook)

MuseumsEducational aspectsUnited States. 2. Childrens museumsUnited States Planning. I. Title.

AM7.S433 2014

069.1083dc22

2014034521

ISBN 978-1-61132-199-9 paperback

ISBN 978-1-61132-198-2 hardback

Contents

George Hein

The Smithsonian Institution, the worlds largest museum complex (30 million visitors annually) has come a long way from its beginning over 150 years ago. The first Secretary, Joseph Henry, who directed the museum from 18461878, was dedicated to science and its progress and dissemination, but he did all he could to avoid having to take responsibility for a museum. The second Secretary, Spencer Fullerton Baird (18781887), devoted his career to making the Smithsonian a great national museum. It was under his administration that George Brown Goode, long recognized as a champion of museums as educational institutions, supported this goal, focusing on the value of museums for higher education. He wrote that museum visits were not likely to be educationally useful for young visitors in the larval stage of development. The next secretary of the Smithsonian, Samuel Pierpont Langley (18871906), devoted enormous energy to creating a childrens room in the Smithsonians original building. He turned the south tower room of the castle into a colorful natural history exhibition with low exhibit cases so children could see the contents. He stipulated that labels should avoid Latin names, since these were of no interest to children. This groundbreaking gallery existed from 19011939. In subsequent decades, education increasingly devolved into separate activities in the growing number of museums within the Smithsonian Institution.

In the 1980s, under the leadership of the ninth Secretary Robert McCormick Adams, the Smithsonian launched two different educational efforts: the National Science Resource Center (jointly with the National Academy of Sciences) and the Smithsonian Early Enrichment Center. The former, now the Smithsonian Science Education Center, focused on elementary school science curriculum, creating major professional development programs for school districts nationwide and forming close alliances with industries interested in science education. The latter effort was a pioneering development in museum education for younger children. Originally serving 32 children in one location, it has grown to serve 150 children ranging from infants to kindergartners in three locations. Although its original population consisted primarily of children of Smithsonian employees, it always had a goal to be a model lab school with a museum-based curriculum; a place that addressed the Smithsonian mandate for sharing knowledge.1 Over its life it has increasingly emphasized and demonstrated the educational possibilities of museums for young children as described in this book.

Sharon Shaffer, founding Executive Director of the Smithsonian Early Enrichment Center, does not dwell on the complex origin of the SEEC that involved efforts by the Smithsonians Womens Council and dedicated Smithsonian educators. Instead, she focuses on the theoretical background that underlies our increasing knowledge of how young children learn, what they learn, and how museums can best play an educational role in child development.

Developmental Theory is one of the great intellectual achievements of the past 150 years. That learning is more than pouring information into originally empty vessels but requires active interaction between individuals and their environment (including the social environment of learners with peers and teachers) is now well understood by researchers and recognized in principle by most educators. But our educational institutions, whether schools or designed informal settings (a broad field that includes museums), still have a long way to go to fully replace more traditional educational methods that linger on out of convenience, habit, or ignorance. To a large extent, museums that rely primarily on objects and interactive exhibits rather than texts and lectures have been freer than public schools to adopt progressive education methods and to embrace the constructivist educational ideals that Dr. Shaffer describes. Unfortunately, the training of museum educatorsstaff, docents and other volunteersseldom sufficiently emphasizes what we know about how people, especially children, learn.

This volume traces the history of the advances in developmental psychology on education and its application to a particular population that has only in the past few decades been embraced in museums: preschool-aged children. Shaffer provides the theoretical background museum educators need in order to comfortably apply these educational methods and offers examples of museums that have adopted constructivist approaches for their educational programs.

The books strength is in its detailed description of pedagogic methods for professional development for educators, with numerous examples of activities helping young children to become actively engaged with the objects they encounter in museums. It also implies the other component of progressive education: its socio-political aspect. Dewey emphasized that education in a democratic society had the dual role of helping children to develop intellectually through activity and to become conscious of their responsibilities towards society so that our society progresses towards more democracy. The other nonmuseum examples in the bookMaria Montessoris educational methods and the Reggio Emilia approach developed by Loris Malaguzzi along with working class parents in northern Italyalso had a goal of providing strong educational experiences for the poorer, underserved populations in their locations.

Sharon Shaffers detailed explanation of advances in developmental psychology and its application to constructivist educational practices as well as her extensive experience in developing programming for preschool children make this book an important contribution to anyone wishing to engage this age group in museums.