Table of Contents

To my father,

who is all heart,

my mother,

who loves a journey,

and to David,

who brought the weary traveler home.

I hear a robin singing, singing,

Up in the treetop high, high

To me and you, hes singing, singing

The clouds will soon roll by.

Somebodys heart is burning, burning

Somebodys heart is burning, burning

Somebodys heart is burning, burning

Because he sees me happy.

ENGLISH LANGUAGE FOLK SONG TAUGHT

IN GHANAIAN COLONIAL SCHOOLS

Let my enemy live long and

see what I will be in future!

PROVERB SEEN PAINTED ON THE

SIDE OF A BUS IN GHANA

Looking for Abdelati

Heres what I love about travel: Strangers get a chance to amaze you.Sometimes a single day can bring a blooming surprise, a simple kindnessthat opens a chink in the brittle shell of your heart and makes you a different person when you go to sleepmore tender, less jadedthan youwere when you woke up.

When my relationship with Michael got too complicated, I did what I always do under such circumstances: fled the country. I know some people think this isnt the healthiest possible way to deal with personal crises, but I figure its my life, and if I want to run from it, I can.

My wandering habit began in childhood, when I was obliged to trundle myself back and forth between my dads house in Kansas, where I spent the school year, and my moms California apartment, where I passed the summer and winter breaks. To everyones surprise, I loved the journey. Whenever my hand passed from my parents protective grip into the cool, neutral grasp of a flight attendant, I felt a reckless, giddy thrill. As I grew older, my meanderings led me farther and farther afield. Id stay put for a year or so, begin to build my career as an actor-slash-writer, and then off Id go. As I traveled to increasingly poorer places, I began to volunteer. I didnt like feeling like a parasite, and the work connected me to a community and gave me a sense of purpose. It also allowed me to stay a long time without spending much money. I picked coffee in Nicaragua, met with human rights groups in Guatemala, dug ditches in the former Czechoslovakia, and tilled the land in rural Maine.

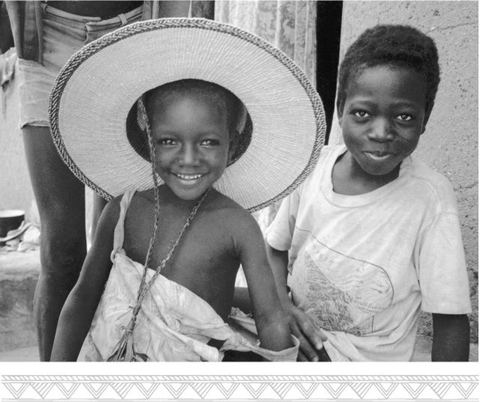

This time, I was headed for Africa. After a year of exhaustive research, Id located a suitable volunteer project in Ghana, a small country on the west coast of the continent, which was renowned for the friendliness of its inhabitants. The organization I was going to work for was extremely flexible. It operated year-round, offering two- to three-week construction projects in villages across the country. On each project, a team of foreign and Ghanaian volunteers worked in conjunction with the villagers to build something: a school, hospital, womens center, or other public edifice. I had little knowledge of construction, but Id worked on similar projects in the past, and I knew theyd take anyone. Somebodys got to shovel and carry, and what I lacked in strength, I made up for in endurance. Id considered projects that mightve made more use of my skillsteaching English, for examplebut those required a commitment of at least a year, sometimes two or three.

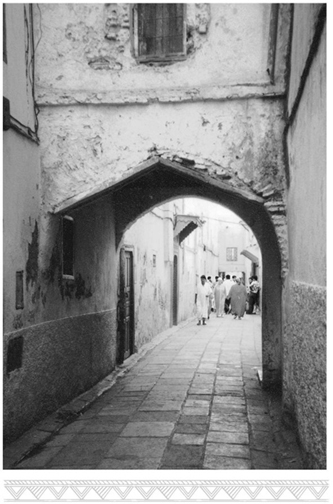

I decided to travel to Ghana the long way, taking in as much of the world as I could en route. I flew to Paris and wended my way by train through the sun-soaked fields of France and Italy, then caught a boat to Morocco, where Id signed up to spend two and a half weeks planting a public park in an ugly industrial city called Kenitra. Seventeen grubby days later, our group of fourteen Moroccans and five foreigners had transformed an uneven plot of dust-dry land into a relatively level one. Wed accomplished this with our shovels and, ultimately, a tractor, which appeared on the last day to finish off the remaining third of the ground. Why it hadnt appeared earlier remains a mystery. The next group, our project leader informed us, would plant the grass and the trees.

When the project ended, I hooked up with a young Spaniard named Miguel for a week of exploring before hopping a plane to sub-Saharan Africa and my next volunteer adventure.

Miguel was one of the five foreigners on our project, a twenty-one-year-old vision of flowing brown curls and buffed golden physique. The fact that his name was Spanish for Michael felt like one of the universes cruel little jokes. Although having him as a traveling companion took care of any problems I might have encountered with Moroccan men, he was inordinately devoted to his girlfriend, Eva, a wonderfully brassy, wiry, chain-smoking Older Woman of thirty with a husky Scotch Drinkers voice, whom he couldnt go more than half an hour without mentioning. Unfortunately, Eva had to head back to Barcelona immediately after the three-week work camp ended, and Miguel wanted to explore Morocco. Since I was the only other person on the project who spoke Spanish, and Miguel spoke no French or Arabic, his tight orbit shifted onto me, and we became traveling companions. This involved posing as a married couple at hotels, which made Miguel so uncomfortable that the frequency of his references to Eva went from half-hour to fifteen-minute intervals, then five as we got closer to bedtime. Finally one night, as we were getting set up in our room in Fs, I grabbed him by the shoulders and said, Miguel, its okay. Youre a handsome man, but Im over twenty-one. I can handle myself, I swear.

On my last day in Morocco before heading to West Africa, Miguel and I descended from a cramped, cold bus at 7 A.M. and walked the stinking gray streets of Casablanca with our backpacks, looking for food. Unlike the romantic image its name conjured, Casablanca was a thoroughly modern city, with rectangular high-rises sprouting everywhere and wide boulevards already jammed with cars. Horns blared, and the air was thick with heat and exhaust. My T-shirt, pinned to my skin by my backpack, was soaked with sweat. We were going to visit Abdelati, a sweet, gentle young man wed worked with in Kenitra. He was expecting our visit, and since he had no telephone, hed written down his address and told us to just show uphis mother and sisters were always at home. Since my plane was leaving the following morning, we wanted to get an early start so that we could spend the whole day with him.

Eventually we scored some croissants and overly sugared panaches (a mix of banana, apple, and orange juice) at a roadside caf, where the friendly owner advised us to take a taxi rather than a bus out to Abdelatis neighborhood. A taxi would only cost fifteen to twenty dirham, he saidless than three dollars and the buses would take all day.

Next page