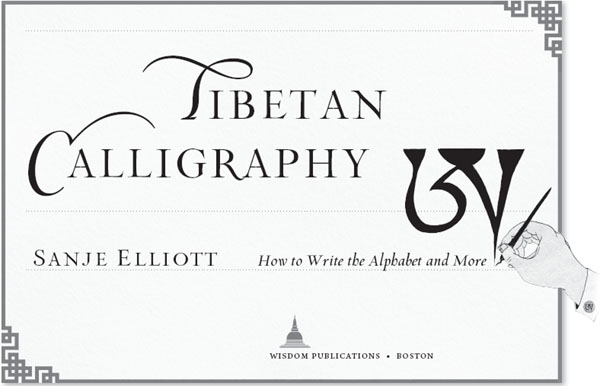

TIBETAN CALLIGRAPHY

Wisdom Publications

199 Elm Street

Somerville MA 02144 USA

www.wisdompubs.org

2012 Frank Sanje Elliott

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Elliott, Sanje.

Tibetan calligraphy : how to write the alphabet and more / Sanje Elliott.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-86171-699-X (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Calligraphy, TibetanTechnique. I. Title.

NK3639.T533E45 2011

745.6199515dc23

2011039573

ISBN 978-0-86171-699-9

eBook ISBN 978-1-61429-028-5

16 15 14 13 12

5 4 3 2 1

Cover design by Phil Pascuzzo.

Interior design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

Set in Arno Pro 11.25/16.

As Long as Space Exits on page 9 and The Four Noble Truths on page 82 are by Tashi Mannox and are used by permission.

The photographs on pages 12, 14, 16, 17, and 18 are by Tendrel Photography.

The art and photography on pages x, 3, 7, and 8 are by the author.

Wisdom Publications books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

This book was produced with environmental mindfulness.

We have elected to print this title on paper that is FSC certified.

For more information, please visit our website, www.wisdompubs.org.

For information on FSC certified paper, visit www.fscus.org.

This book is dedicated to bodhichitta,

the wish that each and every being may achieve enlightenment,

becoming free from the causes of suffering

and suffused with the causes of true happiness.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

T IBET IN THE SEVENTH CENTURY was at the height of its political, economic, and military might, with influence throughout much of Asia and the subcontinent. The great King Songtsen Gampo (61790) had married two Buddhist princesses (considered to be emanations of Green and White Tara), and under their influence Buddhism was flourishing as well. Soon, the king recognized the need of a written script for both his statecraft and to support the spread of Buddhism. He therefore decided to send his prime minister, Thnmi Sambhota, to study in India at the great Buddhist university of Nalanda for some years. Upon his return, Sambhota worked on developing a system of writing that would accommodate the needs of Tibetans and of Buddhism. So it is Sambhota that is credited with the creation of the alphabet and writing system that is still in use.

T IBET IN THE SEVENTH CENTURY was at the height of its political, economic, and military might, with influence throughout much of Asia and the subcontinent. The great King Songtsen Gampo (61790) had married two Buddhist princesses (considered to be emanations of Green and White Tara), and under their influence Buddhism was flourishing as well. Soon, the king recognized the need of a written script for both his statecraft and to support the spread of Buddhism. He therefore decided to send his prime minister, Thnmi Sambhota, to study in India at the great Buddhist university of Nalanda for some years. Upon his return, Sambhota worked on developing a system of writing that would accommodate the needs of Tibetans and of Buddhism. So it is Sambhota that is credited with the creation of the alphabet and writing system that is still in use.

Anam Thubten Rinpoche writes:

Skill in calligraphy was highly regarded as an important subject of study in society. It not only served the holy scriptures, but helped the individual in his or her daily life. The position of Calligrapher elevated one to aristocratic status, and the lifestyle enjoyed as such was far beyond that of the common person. In public schools calligraphy became one of the main subjects of study. At Mindroling monastery [for example], it took six years to graduate in calligraphy.

Tibetan calligraphy continued to evolve over time to include many styles and characters, and its practice is still considered to be a component of one of the ten arts and sciences that relate to individual spiritual practice. The practice ranges from the foundation of perfect penmanship, to the most elaborate and creative flourishes, to the simple strokes of a mind at ease. Above all, calligraphy holds and transmits the word of the Buddha in all its many manifestations, and thus embodies a worthy object of refuge: the Jewel of the Dharma.

Now for us it may seem that the art of Tibetan calligraphy has bifurcated into the two worlds of unicode font geeks and tattoo parlors. But let us not lose sight so easily of this important practice. The written word contains much magic beyond being a simple, or complicated, conveyance of information. Ancient spiritual traditions have always recognized the power of the word, both as utterance and as symbol. The great Buddhist languages, such as Sanskrit, Pali, and Tibetan, manifest this power both explicitly and implicitly. In studying the Buddhist teachings, one has many ways of relating to the media of its transmission. Not the least of these methods is simply beautiful writing.

There is no one more capable of conveying this than Sanje Elliott. A great artist in his own right, he has studied and taught the art of Tibetan thangka painting for many years. He has mastered the traditional, highly refined styles of Tibet and at the same time developed his own creative interpretations. Now in this book of traditional calligraphy, we too can learn the necessary foundation of Tibetan writing, perhaps in order to explore later our own creative relationship with the language. I am grateful for this needed addition to the field and will use it immediately in teaching Tibetan.

Sarah Harding

Thnmi Sambhota, creator of the uchen alphabet.

SARAH HARDING has been the director of the Tibetan Language Correspondence Course since 1987 and an associate professor at Naropa University since 1992. Some of her books include Creation and Completion; Machiks Complete Explanation; The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa; and Niguma: Lady of Illusion.

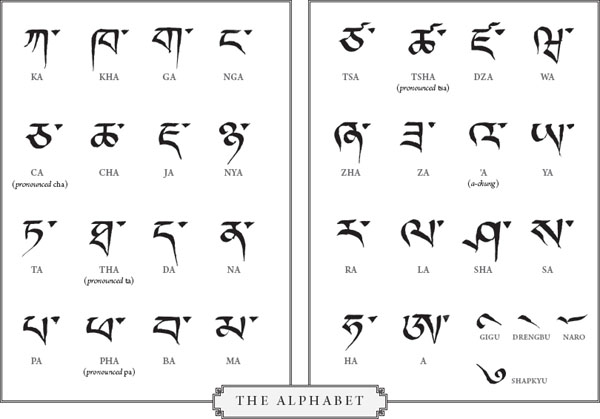

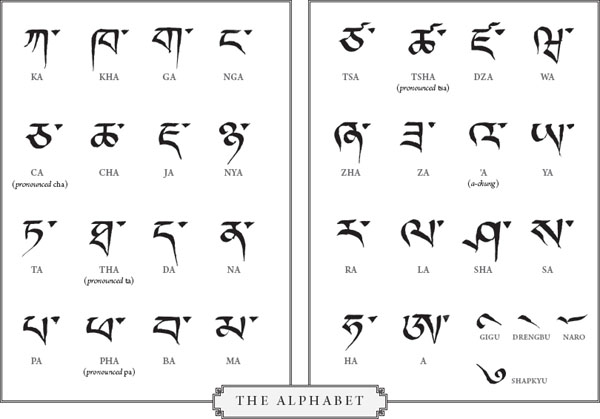

T HE GOAL OF THIS BOOK is to introduce the classical uchen alphabet to Western students of Tibetan and to Tibetans growing up in the West, showing how the flat-edged pen is our equivalent to the reed pen that is the basic beginning tool of Tibetan monks and children. Unlike Chinese and Japanese characters, which are written with a brush, the forms of Tibetan letters are based on Sanskrit letters, which are meant to be written with a pen-like tool. Its true of course that the modern Tibetan master Chgyam Trungpa Rinpoche and those who were inspired by him did wonderfully innovative uchen letters using a brush (see Tashi Mannoxs wonderful calligraphy on page 82), but this is a modern-day alternative to the classical uchen. Classical uchen has many similarities to classical roman letters, such as the crisp serif-like forms and the contrasting thicks and thins, all of which can be accomplished by a penor by a brush in the hands of a very skilled calligrapher.

T HE GOAL OF THIS BOOK is to introduce the classical uchen alphabet to Western students of Tibetan and to Tibetans growing up in the West, showing how the flat-edged pen is our equivalent to the reed pen that is the basic beginning tool of Tibetan monks and children. Unlike Chinese and Japanese characters, which are written with a brush, the forms of Tibetan letters are based on Sanskrit letters, which are meant to be written with a pen-like tool. Its true of course that the modern Tibetan master Chgyam Trungpa Rinpoche and those who were inspired by him did wonderfully innovative uchen letters using a brush (see Tashi Mannoxs wonderful calligraphy on page 82), but this is a modern-day alternative to the classical uchen. Classical uchen has many similarities to classical roman letters, such as the crisp serif-like forms and the contrasting thicks and thins, all of which can be accomplished by a penor by a brush in the hands of a very skilled calligrapher.

One of the interesting differences between Tibetan and the roman alphabet is that roman letters sit on a baseline while Tibetan letters hang from a line, much like clothes from a clothesline. Another thing a student should be aware of is that the Tibetan alphabet employs no cases.

THE MANY USES OF THE TIBETAN ALPHABET

Gega Lama, in his book Principles of Tibetan Art, talks specifically about Tibetan letters and their usage:

Next page

T IBET IN THE SEVENTH CENTURY was at the height of its political, economic, and military might, with influence throughout much of Asia and the subcontinent. The great King Songtsen Gampo (61790) had married two Buddhist princesses (considered to be emanations of Green and White Tara), and under their influence Buddhism was flourishing as well. Soon, the king recognized the need of a written script for both his statecraft and to support the spread of Buddhism. He therefore decided to send his prime minister, Thnmi Sambhota, to study in India at the great Buddhist university of Nalanda for some years. Upon his return, Sambhota worked on developing a system of writing that would accommodate the needs of Tibetans and of Buddhism. So it is Sambhota that is credited with the creation of the alphabet and writing system that is still in use.

T IBET IN THE SEVENTH CENTURY was at the height of its political, economic, and military might, with influence throughout much of Asia and the subcontinent. The great King Songtsen Gampo (61790) had married two Buddhist princesses (considered to be emanations of Green and White Tara), and under their influence Buddhism was flourishing as well. Soon, the king recognized the need of a written script for both his statecraft and to support the spread of Buddhism. He therefore decided to send his prime minister, Thnmi Sambhota, to study in India at the great Buddhist university of Nalanda for some years. Upon his return, Sambhota worked on developing a system of writing that would accommodate the needs of Tibetans and of Buddhism. So it is Sambhota that is credited with the creation of the alphabet and writing system that is still in use.