Sarah A. Corbet ScD

S.M.Walters, ScD, VMH

Prof. Richard West, ScD, FRS, FGS

David Streeter, FIBiol

Derek A. Ratcliffe

The aim of this series is to interest the general reader

in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing the enquiring

spirit of the old naturalists. The editors believe that

the natural pride of the British public in the native

flora and fauna, to which must be added concern for

their conservation, is best fostered by maintaining a

high standard of accuracy combined with clarity of

exposition in presenting the results of modern

scientific research.

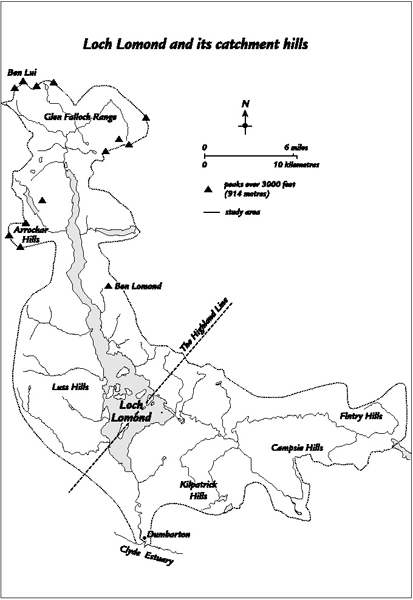

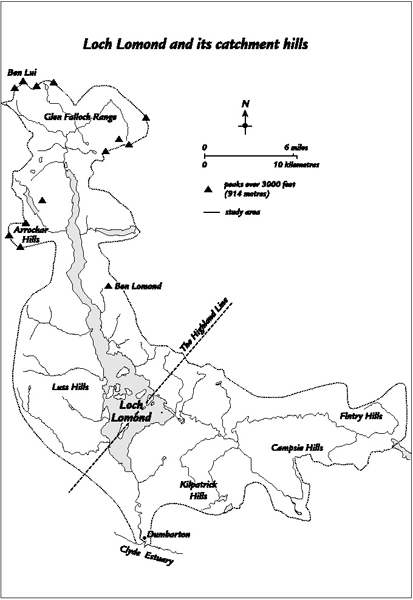

Sketch map of Loch Lomond and its catchment area.

Scotland is the only country in Europe which does not have a National Park. Almost half a century after their establishment in England and Wales, the Scottish Secretary, Donald Dewar, announced in September 1997 that Scotland will have National Parks, with the Loch Lomond and Trossachs area as the first. Yet, despite the fame of the district for its natural and cultural heritage, there has been no single comprehensive treatment to make knowledge of this available to the visitor. The addition of this latest regional volume on the celebrated Loch Lomonside to the New Naturalist Series is thus highly appropriate and well timed.

The district is one of the most diverse and beautiful in the Highlands, ranging from the lowland woods, farms and rivers of the gently contoured southern section, to the Loch itself with its numerous and mostly wooded islands, and the high alpine peaks of the mountains forming the northern watershed. Its natural history is rich and complex in similar measure, and no one is better qualified than the author of this book to do it justice. John Mitchell was, between 1966 and 1994, the Senior Warden of the Loch Lomond and Ben Lui National Nature Reserves established by the Nature Conservancy (now devolved in Scotland as Scottish Natural Heritage). In this role he was responsible for the care and management of the Reserves, including welcoming and informing the visiting public, which he did with great dedication. With the southern end of Loch Lomond lying within 16 km of Glasgow and its two million or so human inhabitants, the loch and its surrounds are extremely popular as a recreational area. There is a great love of the district and a demand for knowledge about it, but also a relentless pressure of people that increases the problems of nature conservation.

Besides his intimate acquaintance with the Reserves themselves, John Mitchell has gained a comprehensive knowledge of the wildlife of the whole district, together with its human history and the interactions between the two. His enthusiasm for animals and plants led him to explore the hidden corners of Loch Lomondside in his spare time, and to write extensively on his findings in the journals of both local and national societies. A natural warmth won him many friendly and helpful contacts among farmers, shepherds, foresters, gamekeepers, fishermen and other countryfolk, to whom he was the Nature Conservancys ambassador in this district. He continues in retirement to live within it, and to add to his 35 years knowledge of the area and its wildlife. This natural history, ecological insight and historical research he has admirably distilled into the writing of this book, which the Editors are pleased to welcome to the series, as in the best traditions of the New Naturalists.

While I gazed on this Alpine region, I felt

a longing to explore its recesses

Frank Osbaldistone in Rob Roy Sir Walter Scott (1817)

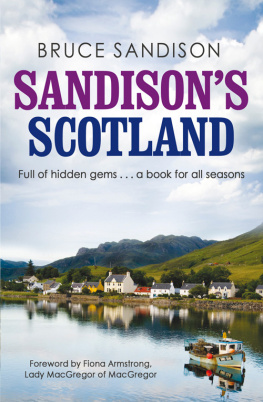

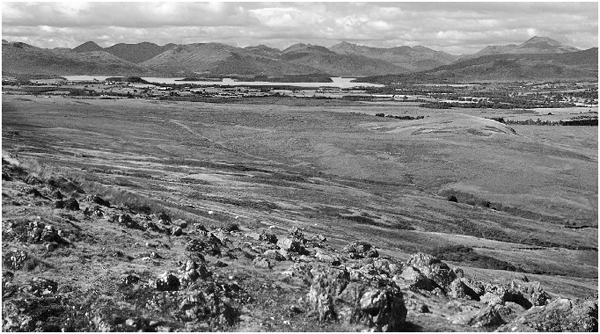

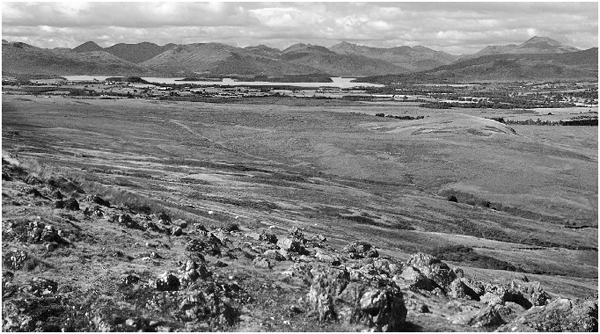

Ever since tales of the adventures of Rob Roy MacGregor first drew Loch Lomondside to the nations attention, generations of travellers have followed in Sir Walter Scotts literary footsteps. They too may have shared Frank Osbald-istones desire to know more of the region on first seeing it stretched out before him on the southern approach, a prospect that has since become known as the Queens View (see Figure below). In the foreground the open moorland with its mosaic of subdued colours gradually falls away to an orderly patchwork of plantations and enclosed green fields. Beyond that and studded with wooded islands is the wide expanse of the loch itself, almost completely encircled by a backdrop of rugged mountains which were once the remote fastness of the Highland clans. Such is its scenic reputation, the area attracts more than two million visitors every year, many from overseas. Landscape entirely un-defaced by man may have long since vanished, yet to most eyes Loch Lomondside still reflects the wild country so vividly portrayed by Scott. And once away from the beaten track and the confines of man-made boundaries, a feeling of open space and solitude may still be experienced, belying the fact that the largest concentration of people living in Scotland is encompassed within a one hour car journey.

Every book has a point of conception, and in this case it occurred some years ago when I was invited to prepare a course of lectures on Loch Lomondsides natural history and nature conservation for the University of Glasgows Department of Further Education. It was the students need for a readily available and modestly priced work on the history and wildlife of Loch Lomond and surrounds that brought together a group of tutors to produce A Natural History of Loch Lomond (1974), a booklet which is still in print and available from the Loch Lomond Park Authoritys visitor centres. The intention of this greatly expanded account is to examine in turn each of Loch Lomondsides component physical, historical and economic features, before describing the principal wildlife habitats and their dependent species, concluding with a summary of the gradual awakening to the national importance of the regions wealth of wild places, plants and animals. Particular attention is drawn to the influence of man on the natural environment, especially those changes brought about by agriculture, forestry, urban and industrial water demands, together with recreation in all its forms. If, as intended, the present work not only answers many of the enquiring readers questions as to what, where and when, but stimulates a wider awareness of the significance of Loch Lomondsides diverse wildlife heritage, then the books aim as a New Naturalist will have been achieved.

Loch Lomondside from near the Queens View.

In the gathering of material for the book, help has been forthcoming from many directions. First I would like to acknowledge a considerable debt to all those historians, geographers and biologists past and present who have published or permanently recorded in some way the results of their investigations in the Loch Lomond area. Without such a rich legacy of the written word to draw upon, the project could not even have begun. Considerable assistance with obtaining these publications and reports was given by Scottish Natural Heritage, Stirling and Dumbarton library services. Thanks are also due to fellow members of the Loch Lomond & Trossachs Research Group (based at the University Field Station near Rowardennan) for helpful discussions on various subjects outwith my own experience. Similarly, I would like to extend my thanks to a number of former colleagues in the Nature Conservancy Council and associates at the Universities of Glasgow, Paisley and Stirling, the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, the Natural History Society of Glasgow and the Scottish Entomologists Group, who generously made available their expertise on specialist groups from bryophytes to beetles, freshwater life to fungi. Members and staff of the Scottish Ornithologists Club, the British Trust for Ornithology, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, the Botanical Society of the British Isles, the British Bryological Society, the British Lichen Society, the Scottish Wildlife Trust, the National Trust for Scotland, the Forestry Commission and the Loch Lomond Angling Improvement Association have between them furnished many additional biological records. The Scottish Climate Office in Glasgow kindly provided much of the recent meteorological data. A large proportion of the accompanying photographic plates and figures have been drawn from my own collection; those from other sources are individually acknowledged. Preparation of these photographs for publication was undertaken by Norman Tait.