SARAH A. CORBET, ScD

PROF. RICHARD WEST, ScD, FRS, FGS

DAVID STREETER, MBE, FIBIOL

JIM FLEGG, OBE, FIHORT

PROF. JONATHAN SILVERTOWN

The aim of this series is to interest the general reader in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists. The editors believe that the natural pride of the British public in the native flora and fauna, to which must be added concern for their conservation, is best fostered by maintaining a high standard of accuracy combined with clarity of exposition in presenting the results of modern scientific research.

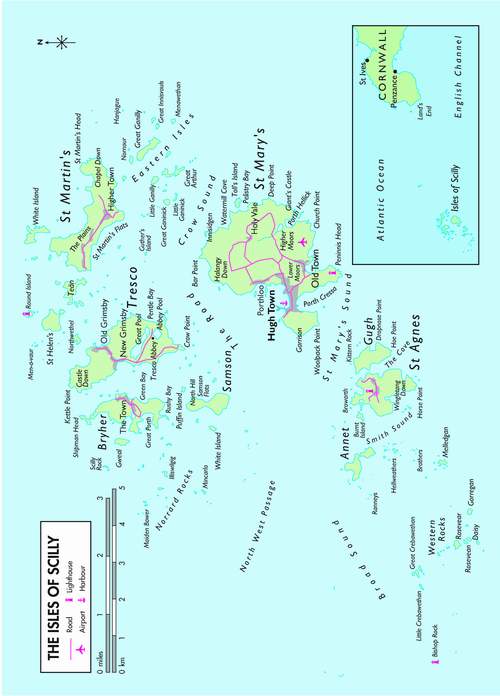

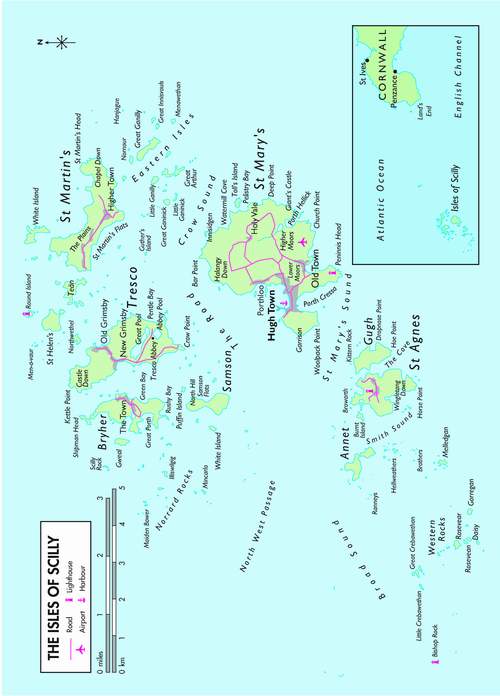

E ARLIER VOLUMES OF the New Naturalist library have concerned the natural history of the islands of northern Britain the Highlands and Islands (1964), Shetland (1980), Orkney (1985) and the Hebrides (1990). Here, in the Isles of Scilly, a group of islands at the extreme southwest of Britain presents a totally different aspect of island natural history.

Any account of the natural history of the Isles of Scilly has to comprehend an unusually wide variety of life and environments. In this striking archipelago of inhabited and uninhabited islands, southwest of Lands End and on the fringes of the Atlantic, marine and terrestrial natural history are intimately connected. The oceanic climate, with mild summers and winters and stormy weather, exerts a strong influence, resulting in a flora and fauna unique in Britain. Added to this is the effect of thousands of years of human occupation, governed by changing economic conditions and isolation from the mainland, a history which has produced, for example, an extraordinary mix of native, introduced and cultivated plants.

The author, Rosemary Parslow, has an unrivalled knowledge of the natural history of the Isles of Scilly, gained over nearly fifty years of active involvement in observation and survey. Her studies have included the marine life and the life of terrestrial environments, including both fauna and flora. With such a range of practical experience, she is in an excellent position to give a synthesis which covers the variety of natural history of the islands, as well as issues of conservation and future development. Such a synthesis will be welcomed by Scillonians and by the many visitors to the islands, as well as by those with wider interests in the British fauna and flora.

H OWEVER OFTEN YOU go to Scilly it is still a magical experience as the islands slowly emerge out of the line of clouds on the horizon, to resolve into a mass of shapes and colours against the sea and sky. Whether you go there by boat, stealing up gradually on the islands, or by air, flying in low over the coastline of St Marys to land with a rush on the small airfield like one of the plovers that feed there on the short turf it brings a thrill of excitement every time.

I first went to Scilly in 1958, to stay at the St Agnes Bird Observatory that had started up the previous year. It was an un-manned observatory, run by a committee of enthusiastics, organising self-catering holidays for groups of bird-ringers to operate it as a ringing station over the spring and autumn migrations. The first year had been based in tents at Lower Town Farm, but by the time of my visit they were renting the empty farmhouse. Like many similar establishments they ran on a small budget and lots of commitment; the living conditions were very basic, but the surroundings idyllic. That first visit was the start of a lifetime love affair with Scilly, which has influenced my whole adult life and has led to writing this account of the natural history of the islands.

Those early visits were made when I was working as a very junior scientific assistant at the British Museum (Natural History) in South Kensington. At that time collecting specimens was still an important element of the work, in order to build up the Museums taxonomic collections. So staff holidays often became unpaid collecting trips, and mine were frequently timed to go to Scilly at the best times for shore collecting, to collect marine invertebrates. These were when the equinoctial spring tides occur, around Easter and again in autumn, when the most extensive areas of shore are exposed. This was in the days before cheap wet suits and underwater photography meant that marine biologists were no longer constrained by tides. At that time it was boulder-turning and wading and following the tide down to the lowest level accessible, laden with heavy collecting gear. Most of the collecting I did was to order: specific groups of animals were targeted because these were ones where information on their distribution and status was needed, as well as adding representative specimens to the Museum collections. This resulted in a series of Isles of Scilly collections in the 1960s and 70s, mostly shore fishes, sponges, worms, and other invertebrates, especially echinoderms, my specialist group.

Even after I had left the Museum, a colleague would send a small milk churn packed with collecting paraphernalia to the island of St Agnes to await my arrival for the family holiday, and then we would return it with the carefully preserved and labelled specimens packed inside. This system usually worked very well, but in the early days there were some hiccups like the time the churn was nearly dispatched to Sicily due to a misunderstanding with the carriers, or the year it was put back on the launch by a puzzled islander because he did not know anyone who used milk churns on the island!

This first-hand experience firstly the shore collecting, then the species records when collecting specimens became unfashionable, my involvement with the bird observatory, and then starting listing plants was fortuitous in that it gave me a unique opportunity to study, photograph and get to appreciate the wildlife, scenery and history of these enchanting islands. I have been fortunate in that I was also to spend many weeks over the succeeding years on Scilly, usually based on St Agnes, and later St Marys.

Since those early days I have visited the islands at least once every year (except for a break of a couple of years in the late 1960s), have had several prolonged stays, and have been there in every month of the year and probably most kinds of weather. This has probably been the best way of getting to know as much as possible about the islands without being resident there. At various times I have been employed to survey and produce reports on a number of subjects from bats to plants. In 2002 I was commissioned to write a Management Plan for the land leased by the Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust. This gave me a further opportunity to spend a longer time on the islands, getting to know them, their habitats and the people whose job it is to manage those habitats (Parslow, 2002).

Due to the climate and the geographical position of the islands there are some species, particularly plants, which are not usually easy for the holiday visitor to see. Certainly if you want to see some of the plants which flower in the middle of winter, such as some of the introduced aliens, German ivy Delairea odorata and some of the Aeoniums, then a visit at Christmas or New Year is essential. This is also a good time to find the tiny least adders-tongue fern Ophioglossum lusitanicum, a great rarity found in Britain only on the Channel Isles and on St Agnes in Scilly. Every month has its specialities, so there is always something to look out for at any time of the year. If your interests are more ornithological then everyone will recommend the spring and autumn migrations for the falls of unusual migrants. In summer there are breeding seabirds, and a boat trip can take you out to see puffins, shags, guillemots, fulmars and other seabirds among the uninhabited islands and there are also grey seals hauled out among the distant rocks. Even in winter there are peregrine and raven to look out for, and sometimes in cold weather large numbers of woodcock seem to fall out of the sky. For the other natural history groups, lichens, insects, fish or seaweeds, there are nearly always things to do and things to see!