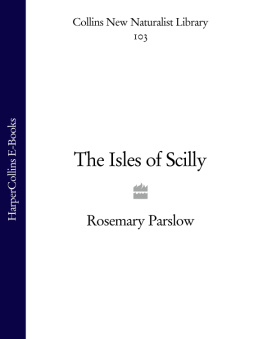

PREFATORY NOTE TO FIRST EDITION

I T has been said that all writers may be divided into two classes: those who know enough to write a book, and those who do not know enough not to write one!

In collecting material for these notes on Scilly, I have endeavoured to prepare myself more or less to qualify for the former class; but now that they are complete it is with diffidence that I present them. They are but the impressions of an artist, recorded in colour and in ink, together with so much of the history of the islands and of general description as is necessary to comply with the unwritten law of colour-books.

For my historical facts I am indebted to many writers, ancient and modern. A list of the chief of these appears at the end of the book, so that my readers may refer, if they wish, to the original authorities.

My best thanks are due to Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, for permission to quote his description of the kelping, and for other help he has kindly given me; to my friend Miss Emma Gollancz, for seeing my proofs through the press; and also to the many friends in Scilly from whom I have received assistance and information.

October, 1910.

NOTE TO SECOND EDITION

This second edition of The Isles of Scilly is issued in response to many requests that the book should appear in a cheaper form, the original edition having completely sold out.

A few slight alterations in the letterpress have been necessary, to correspond with changes that have taken place in the islands; but otherwise the contents are identical with those of the original issue.

Pilgrims Place House, Hampstead.

March, 1914.

I

INTRODUCTORY

A COLOUR-BOOK on Scilly needs no apology, so far as the subject is concerned, for there is no corner of Great Britain which more demands or deserves a tribute to its colour than do these little islands, scattered about in the Atlantic twenty-eight miles from the Lands End.

For they are all colour; they gleam and glow with it; they shimmer like jewels set in the silver sea. No smoke from city, factory, or railway contaminates their pure air, or dims the brilliancy of their sunshine. They are virgin-isles, still unspoiled and inviolate in this prosaic age, when beauty and charm are apt to flee before the path of progress.

And though their compass is but small, the same cannot be said of their attraction, which seems to be almost in inverse proportion to their size. Scilly exerts a spell over her lovers which brings them back and back, again and yet again, across that stretch of the vasty deep which separates her from Cornwall. In this case it might almost better be called the nasty deep, for very nasty this particular stretch can be, as all Scillonians know!

Nor do the islands lack variety. There are downs covered with the golden glory of the gorse, with the pink of the sea-thrift, with the purple of the heather; there are hills clothed with bracken breast-high in summer, and changing from green-gold to red-gold as the year advances; there are barren rocks on which the sea-birds love to gather; there are lovely beaches of white sand, strewn with many-coloured shells and seaweed; there are clusters of palm-trees growing with Oriental luxuriance, next to fields and pastures where the sheep and cattle feed; there are bare and dreary-looking moors, the sad sea-sounding wastes of Lyonnesse; there are stretches of loose sand, some planted with long grass to keep the wind from lifting it, some with a mantle of mesembryanthemum, which here grows wild like a weed;and all of them seen against a background of that wonderful and ever-changing sea, which is sometimes the pale blue of the turquoise, sometimes the deepest ultramarine, sometimes again shimmering silver or radiant gold. And then in spring there are the famous flower-fields. Let us visit the islands on an April day, and see for ourselves this harvest of gold and silver. For once we will be day-trippers in fancy though we would scorn to be in fact.

Here in Scilly we find land and sea flooded with spring sunshine, while on the adjacent island which we have just left every one is lamenting the cold and the rain. The flower-harvest is nearly over, yet still there are wide fields of dazzling white and yellow, and many hundreds of boxes will yet leave the quay for the mainland. The sweet-smelling Ornatus narcissus is now at its best, and its perfume fills the air. Arum-blossoms, thousands of them in a single field, stand stiffly waiting to be cut, while in the more exposed places late daffodils linger, nodding their yellow heads in the breeze that comes in from the sea. Everywhere there are flowers, flowers, flowerssuch a wealth of flowers as one never saw before; and every one is either picking flowers, tying flowers, packing flowers, selling flowers, buying flowers, or talking of flowers. Even the tiny children can tell you the difference between a natus and a Pheasant Eye; and will talk wisely in a way to awe the less enlightened visitor of Cynosures, Sir Watkins, and Peerless Primroses.

It is barely thirty years since these sweet flower-fields first began to cover the islands. The oldest inhabitant, a great-grandmother of ninety-six (she died in 1913), would call to mind the kelp-making industry which occupied the people in her young days. Eh, she would say, it was not a nice employ; things are better as they are. And we can easily believe that she was right; for instead of the fragrance of the flowers the air was then filled with the thick and acrid smoke of the burning seaweed; and it was but a poor living at the best that could be made out of it.

There is now hardly a boatman in the islands who does not add to his income by having a patch of ground planted with the lilies, as they call them, and sending his boxes of blooms to market during the season.