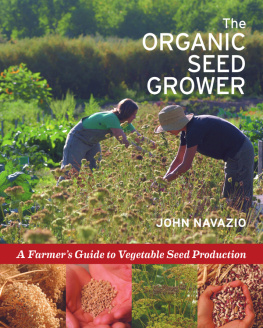

The

GRAPE

GROWER

The

GRAPE

GROWER

______________________

A Guide to Organic Viticulture

by Lon Rombough

CHELSEA GREEN PUBLISHING

White River Junction, Vermont

Copyright 2002 Lon Rombough.

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs copyright 2002 Lon Rombough.

Illustrations copyright 2002 Elayne Sears.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted in any form by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover designed by Ann Aspell.

Interior designed by Andrea Gray.

Printed in Canada.

First printing, October 2002.

05 04 03 02 1 2 3 4 5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rombaugh, Lon, 1949

The grape grower / by Lon Rombough.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-60358-082-3

1. GrapesUnited States. 2. ViticultureUnited States. 3. Grapes. 4. Viticulture. I. Title.

SB389.R76 2002

634.80973dc21 2002023371

Chelsea Green Publishing Company

P.O. Box 428

White River Junction, VT 05001

(800) 639-4099

www.chelseagreen.com

This book is dedicated to

Dr. H. P. Olmo

Elmer Swenson

Byron Johnson

Robert Zehnder

D.C. Paschke

for what I learned from them,

both in information and dedication

to grapes, and especially to my wife

Susan for her love and support

through the effort of producing this book

Contents

, by Roger B. Swain

Foreword:

Seed Matters

R ELIEF FROM THE SUN was what my grandmother had in mind when, early last century, she requested a grapevine be planted outside the kitchen door of her new farmhouse. At midday, in midsummer, in the Midwest, even the cows seek out shade. And shade she got, as the vine topped the arbor of chestnut posts and split rails. Beneath its leafy canopy, peas were shelled, beans snapped, and babies nursed. My mother washed her hair in a bucket there and walked out into the light on her wedding day. I remember, as a young boy lying on the vine-cooled terrace beneath the arbor, the contrast between the cool of the sandstone paving and the hot whine of cicadas in overdrive in the elm branches above the barn.

The Guernsey dairy herd is gone now, so too the American elms, and grandmother herself. But the grapevine lives on. The arbor is on its third generation of posts, but the vine is still an adolescent. Compare it, for example, to the Great Vine at Hampton Court Palace in England, which was planted in 1768 and still bears an annual crop of fruit. Barring someone uprooting Grandmothers vine in a burst of ill temper at having had to sweep the fallen grapes off the terrace one time too many, it will someday be as venerable. Key to its survival is the fact that grapevines are so extraordinarily self-reliant. It helps, of course, that grapes are native to North America, but this vine to my knowledge has never been given much more than earth, water, and sun. Its pruning has been no more sophisticated than cutting back the shoots that attempt to mount the roof, or threaten to seal off the arbors entrances. Unsprayed, it still yields fruit sufficient to keep the jelly jars filled.

In my own vineyard, the vines receive considerably more attention. The training, pruning, and feeding are all directed at producing the largest and most perfect bunches of grapes that genetics and the land will allow. This is not Ohio but south ern New Hampshire, and a cool mountainside is hardly prime grape-growing terrain. Nevertheless, it has proven hospitable to a score of the earliest-maturing and hardiest selections (two characteristics that are not necessarily linked). Despite the famous unpredictability of New Englands weather, these vines reliably produce more grapes than any one family could ever eat.

Our friends think we should be making our own wine. But with only one or two vines of each kind of grape, any wine we might fashion would resemble too closely those blended wines that are available for five dollars a jug at the nearest convenience store. At the end of the season, when killing frosts have turned the leaves brown and crisp, and brought an end to any further accumulation of sugar, we do strip the vines of fruit thats left, turning it into either juice or raisins. Most of our fruit, though, gets eaten fresh.

We entertain by reaching under the leaves for yet another full bunch on a sunny September afternoon, grooming it quickly to remove the imperfections, the fruit that the wasps have discovered first. And then, without disturbing the delicate waxy bloom that coats the individual berries, we offer up the entire bunch to someones lips. Some guests prefer to feed themselves, but even they exhibit refreshingly little reluctance in sampling whatever is available. Each of these grapes is different, and not just because of their hue. This deep blue one is slip-skin, reflecting its American heritage; this adherent-skin red, on the other hand, has European wine-grape genes. Some of the grapes are unmistakable in their foxiness; some have just the tiniest hint of clove. That last one was solid-fleshed; this one almost pure juice.

But while the grapes being offered usually vary widely, the responses they elicit do not. By now we know what to expect, especially from first-time visitors. Seeds! Seeds! the person sputters. Theyve got seeds!

Of course they have seeds, I patiently counter, Grapes are supposed to have seeds. Outside of grocery stores, seeds in fruit are the norm. At what point in recent history did we forget that the purpose of a fruit is to deliver its seeds? Fruiting plants, grapevines included, surround their seeds with a layer of edible flesh that only becomes sweet and attractive when the seeds inside are mature and ready to be dispersed. Frugivores, or fruit eaters, including all of us who like the taste of grapes, are supposed to spread these seeds in return for the sweet mouthful. Shirk our responsibility, and natural selection will replace the sweet pulp with dry, paper airfoils (like maple seeds) or whatever other method of seed dispersal that time and evolution happen to serve up.

Its not that seedless grapes are new. They arent. The word currant is a contraction of the name raisins of Corinth, referring to the small, seedless grapes grown in ancient Greece. But the present preponderance of Flame Seedless, Perlette, and Thompson Seedless in the produce sections of supermarkets is due less to any superiority of flavor than to the pacification of a generation of picky eaters, child and adult alike.

Lest anyone underestimate the importance of seeds, consider what has come from the four or fewer small brown pips contained in a grape. At last count, the worlds individual grape varieties numbered over ten thousand. Less than one percent of those have resulted from a mutation to an existing vine. The rest got their start as seedlings.

Just one such seedling eventually yielded Grandmothers vine. In 1843, an amateur viticulturist named Ephraim W. Bull sowed some seeds from a wild grape at his home in Massachusetts. A gold beater by profession, he subsequently named one of the seedlings after his hometown, and exhibited the fruit of the new Concord grape at the Massachusetts Horticultural Society show of 1852. In 1865, it was awarded the Horace Greeley Prize as the best grape for general cultivation. The best known of the eastern table grapes, it continues to be instantly recognizable today.

Grandmothers Concord grapevine found its way west to Ohio as a rooted cutting, a form of vegetative propagation intended to preserve the genetic integrity of the original plant. I, too, have a Concord vine, but only one in four years do I harvest any ripe fruit. The variety needs 140 frost-free days to mature. Mine shakes off temperatures of twenty below zero during the winter but most years the fruits freeze before they have had a chance to sweeten. The grapes that I grow that look, and taste, like Concord are all newer varieties, the fruits of careful selection among seedlingsgrapes like Worden, which ripens a critical two weeks earlier, and Alwood and Price, which mature earlier still. For such improvement, we again have grape seeds to thank.

Next page