Dedication

It was at my desk, in Pennsylvania, working on this book, that I heard the first plane had hit the World Trade Center. For some time afterwards, it was hard to write about sweet peas as we mourned for so many strangers, so needlessly dead, and sorrowed for the loved ones left behind to grieve.

But the book was finished and you have it in your hand. I will not presume to dedicate a mere gardening book to the memory of so many, so tragically lost. I simply urge you to use its advice to help you make your small part of the world more beautiful.

...Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou sayst,

Beauty is truth, truth beauty, that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

From Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats

Graham Rice 2002

First published in the UK in 2002 by B T Batsford, London, UK

All photography judywhite/GardenPhotos.com except where indicated on page 144.

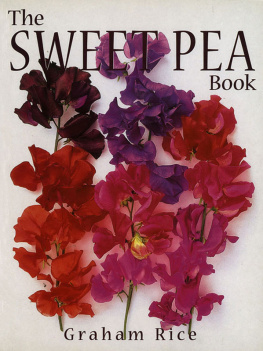

Title page picture Peacock.

eISBN 9781849942126

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Batsford

1 Gower Street

London WC1E 6HD

Introduction

This is a book for gardeners, for gardeners who grow sweet peas in beds and borders, tubs and even hanging baskets; for gardeners who sow a packet of mixed seed in the spring or dozens of individual varieties in the autumn; for gardeners who grow sweet peas for their fragrance and their colour and for cutting for the house.

Sweet peas are not difficult to grow. I will outline how to go about it with the least possible time and trouble, but to grow them well requires careful attention; this, also, I explain. Growing sweet peas up a clump of brushwood or a wigwam of bamboo canes is relatively straightforward and works well, but few gardeners integrate sweet peas into their border plantings or use them to create inspiring and attractive plant associations; I have many suggestions which I hope will provide inspirations in using these versatile flowers.

The explosion of interest in hanging baskets and other containers seems to have swept along without carrying the sweet pea in its wake, yet both traditional varieties and new types can be grown in containers: I will explain how and provide some enticing ideas for plant combinations.

Much of what has been written on sweet peas over the decades has been aimed at exhibitors, but these devotees are but a small minority of those enthusiastic growers for whom sweet peas are such a delight. Exhibitors have pioneered ways of growing sweet peas, researched their history, their peculiarities and their pests and diseases; they have raised many new varieties. Their contribution to sweet pea growing is enormous but they are still a minority: in the United States they are practically non-existent. I discuss exhibiting, and breeding, sweet peas but my interest is more to help gardeners grow better sweet peas and use them more widely and more imaginatively in gardens.

Sweet peas were once the most widely grown of flowers; this may no longer be true, but these are exciting times in the sweet pea world. We have new dwarf sweet peas for hanging baskets, we have new varieties in the highly scented old-fashioned style, and we even have a revival in tall varieties without tendrils. There is also the possibility of a truly yellow sweet pea on the distant horizon, rather than far beyond it. Sweet peas are definitely back. Not as a show flower, but in gardens. It starts here.

NOTES TO READERS

I have used the word variety, rather than cultivar, throughout in recognition of the fact that this is the term which most gardeners actually use for a cultivated variety. I apologize to those purists who may be offended by this affront to botanical correctness.

This book is written with both British and American readers in mind. Occasionally, there are remarks which may seem simplistic to readers in one country but which are helpful to those in the other and I would ask that readers not be irritated by this attempt to please all the readers all of the time.

The flowers in the studio photographs came from plants grown at Unwins Seeds near Cambridge, the Royal Horticultural Societys Garden at Wisley, Surrey and Sweet Pea Gardens, Surrey; our thanks go to all. Flowers also came from my own garden.

Chapter One

From the wild to our gardens

T he native habitat of the wild sweet pea, Lathyrus odoratus, and its earliest introduction into the gardens of Western Europe, is a surprisingly contentious issue, provoking wildly contrasting opinions even today. Sweet peas have been taken all over the world, the robustness of their seeds having certainly been a help; whatever varieties are taken and grown, when they escape into a suitable climate they eventually revert to something approaching a wild type. This causes confusion.

Sicily, China, Malta, Sri Lanka all have been suggested as the wild home of the sweet pea. But there is one aspect of the historical story on which most people now agree: in 1695 Francisco Cupani recorded the sweet pea as newly seen in Sicily. Cupani was a member of the order of St Francis, but he may not actually have been a monk as we have always assumed. He was in charge of the botanical garden at Misilmeri (15km/9 miles from Palermo) in Sicily and it is assumed that his garden was attached to the monastery although it is not entirely clear if his sweet pea was actually growing in the garden or wild in the surrounding area. In 1696, before Linnaeus simplified plant nomenclature, Cupani published a written description of the plant which he called Lathyrus distoplatyphylos, hirsutus, mollis, magno et peramoeno, flore odoro.

In 1699 he sent seed to Dr Casper Commelin, a botanist at the School of Medicine in Amsterdam, who included what is the first illustration of the plant in his account of the plants at the School published in 1701 where he records that the seeds came from Cupani. While there is no concrete contemporary evidence, it also seems clear that Cupani sent seed to Dr Robert Uvedale at the same time.

Dr Uvedale was a teacher who lived at Enfield in Middlesex and was a noted enthusiast for new and unusual plants; he enjoyed a very wide circle of notable friends and his was a well-known and much-visited garden. The first evidence of the plant being grown by Uvedale comes in 1700 on a herbarium specimen made by Dr Leonard Plukenet now at the British Museum (Natural History) in London. A note on the specimen refers to it having been collected from Uvedales garden. British botanical pioneer John Ray also picked up on this new introduction, describing it in his Historia Plantarum of 1704 as: Lathyrus major e Siciliae; a very sweet-scented Sicilian flower with a red standard; the lip-like petals surrounding the keel are pale blue.

So, Cupani noticed the sweet pea, his being the first printed reference. He definitely sent seed to Commelin and it seems most likely that he also sent seed to Uvedale. So far, so good.

There has long been a theory that sweet peas originated in Sri Lanka (Ceylon). In 1753 Linnaeus uses the name Lathyrus zeylandicus for a pink and white-flowered species supposedly originating in that country and this, with other red herrings, led the great authority Bernard Jones to believe as late as 1986 that sweet peas did, indeed, originate there. A much-respected earlier authority, E. R. Janes, held a similar conviction in 1953.

Next page